After the deaths of antifascist Surrealist artist pair Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore in 1954 and 1972, respectively, their artwork and writings fell into obscurity until the 1980s when art historian François Leperlier unearthed the parts of their oeuvre spared from Nazi hands. Coinciding with an era of feminist interventions in art’s discourses, Cahun and Moore’s coupledom, gender nonconformity, and many masked self-portraits readily dovetailed with the era’s sexual politics. The pair was quickly incorporated into the new and substantive attention being paid to women artists’ affronts to the modern male gaze. Some narrated Cahun as a proto–Cindy Sherman, ceaselessly swapping disguises to play with the camera’s production of sexual difference. Meanwhile Tirza True Latimer’s and Abigail Solomon-Godeau’s research invaluably situated Cahun and Moore within the 1920s Parisian lesbian subcultures where gender and sexual deviance were wielded in defiance of patriarchal power.1 Though the 1990s was also a period in which trans scholars sought to correct the archive by recovering forgotten and miscategorized trans histories, Cahun and Moore’s gender nonconformity did not cue parallel research in trans cultural studies. This was likely in part due to the fact that Cahun and Moore had not expressed unequivocal desire to become men, instead leaving behind an archival battery of twisted gender signals. Accordingly, the discovery of Cahun and Moore’s oeuvre slipped through the shadow of an eclipse at the temporal convergence of feminist and trans scholars’ oversight of trans nonbinary subjects.

More recent examinations of Cahun and Moore’s work have described the pair as prototransgender artists. Latimer now describes Cahun’s writing as “textual transvestitism” (travestisme) aimed at resisting identification according to social gender constructs.2 Christy Wampole connects Cahun’s adopted name and appearance to twenty-first-century genderqueer identities, arguing that photographs of Cahun’s “impudent gaze” that displayed “transgender signals” of shamelessness are a prototype for today’s trans self-representations.3 However, contemporary texts and exhibitions largely continue to describe Cahun and Moore as lesbian women, underscoring the need to transvalue Cahun and Moore according to current scholarship for identifying nonbinary historical figures who are not plainly legible as trans. Historians, and curators’ reliance upon “accurate” period terms which lacked trans terminology flattens the complex fabric of histories of gender in the West, which testify to the constant presence of people who clashed with gender conventions.4 That those individuals often do not conform to today’s familiar trans narratives does not invalidate their identification as trans but instead allows us to develop more comprehensive frameworks for making sense of trans subjectivity.5 As Robert Mills writes, the continuation of “epistemological violence” which fails to recognize historical subjects as trans nonbinary within their own era also “risks impoverishing our sense of the past as a field of possibility, plurality, and difference.”6

I argue that not only did Cahun and Moore live trans lives but their artwork deliberately opposed the medical and psychological discourses of their era which sought to find the “truth” of binary gender “within” trans and intersex subjects. Working with the camera’s ontological cut of the visible surface of reality from its substance, they mobilized photography to challenge the fallacies of scientific discourses while visualizing alternatives for a self-determined embodiment that reconfigured the body’s exterior without sacrificing the interior’s integrity for the false prize of cultural legibility. As such, their work offers insight into a trans-before-transsexuality somatic imaginary which anticipated transsexual medicine with trepidation. Their photographic theorization of trans selfhood described a stridently misfit corporeality politically engaged with broader struggles for liberation, rather than one aimed at harmonizing with mainstream heteronorms. Though contemporary terminology and conceptions of trans identity are certainly not exactly what the artists imagined for themselves, I demonstrate that trans people’s underground engagement with Cahun and Moore’s work was in fact palpable within the 1990s and 2000s movement to break from the female-to-male/male-to-female (FTM/MTF) transsexual mold, constituting a trans temporal “touch” that effected the emergence of more porous forms of trans identity. This fact complicates the idea that it is more accurate to read Cahun and Moore as lesbians, instead suggesting that the emergence of supposedly new nonbinary identities are in some cases the outgrowth of Cahun and Moore’s purposeful stitching together of past, present, and future fields of possibility.

I also assert that the use of gender-neutral “they” pronouns productively points to Cahun and Moore’s authorial voice. Cahun’s ceaseless revision of their own ever-emerging identity beckons a correspondent historical practice that regularly reappraises what we once thought to be true of them. Cahun described themself as “neuter” and “me, he she—or simply it”—a subjectivity made up of a “collection of exceptions” to syntax’s rules.7 This shuffling of gendered speech is a familiar characteristic of the trans historical archive. Carolyn Dinshaw points to such binary-crossed language as the very confusion of categories that announces trans presence in historical documents.8 As I explore here, “they” does not suggest an oversimple relationship between trans now and then but instead fruitfully entangles past and present perversions of normative gender.9 In other words, it is not an invocation of sameness but a mapping of shared conduits for gender’s troublesome fluidity. “They” also functions as both singular and plural, signaling the merger of subject and gaze in their collaborative self-portraits, described as “portrait of one or the other, our two narcissisms drowning there.”10 I further continue that merger by allowing Moore to selectively slide above and below the text, as they did in the oeuvre they produced with Cahun—where they were frequently behind the camera for Cahun’s “self portraits” or the unnamed coauthor of texts. Their major written work, Disavowals; Or, Cancelled Confessions (Aveux non avenus, 1930), forcefully blurs the source of authorial voice, consistent with the obfuscating function of singular plural pronouns. In a section of the text entitled “Singular Plural,” they state, “I am one, you are the other. Or the opposite . . . . It’s hard enough just to disentangle them.”11 “They” thus accounts for both gender and the deliberate slippage of identity between Cahun and Moore while extending that slip to the trans temporal lapse through which their time touches our own.

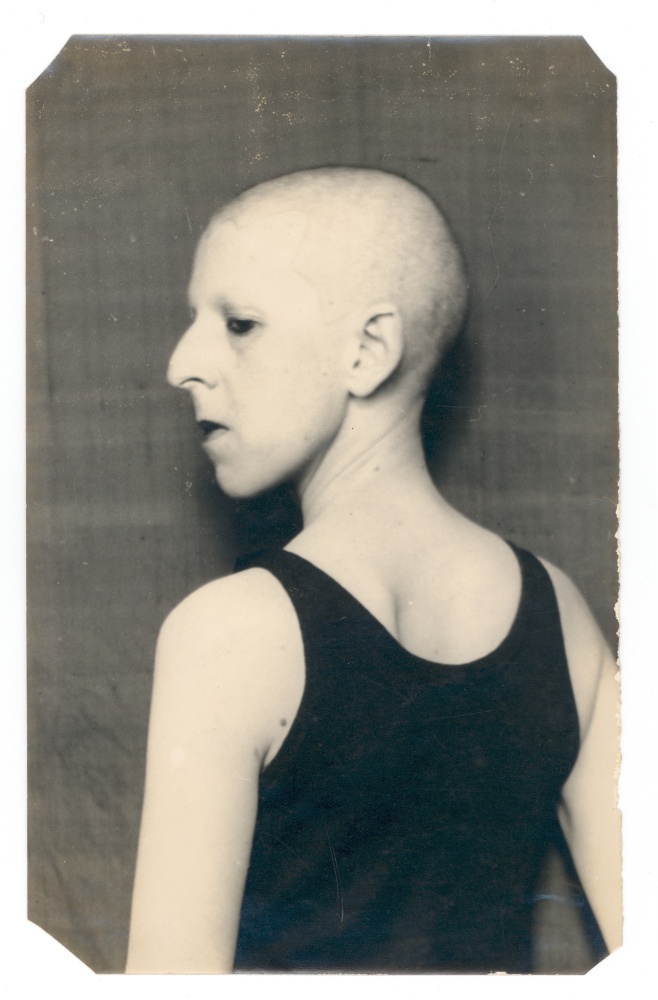

Cahun was born into an influential family in Nantes, France, in 1894, meeting Moore as a teenager and later becoming stepsiblings. The pair quickly became inseparable and remained together as lovers, collaborators, and political agitators throughout their lifetimes. Living in Paris during the 1920s and 1930s, they adopted gender-ambiguous names and became versed in contemporary sexological literature that sought to describe homosexuality and gender variance.12 Cahun consistently contradicted social expectations for both men and women, even within the fringe lesbian and Surrealist subcultures which both entertained gender-crossing appearances. In snapshots Cahun adopts a variety of gender embodiments over the course of their lifetime. During their teens and early twenties they predominately appear in the attire typical of effeminate male homosexual figures. Later they add to this a myriad of feminine, androgynous, and gender-illegible styles. Their oft shaved head was atypical for lesbians, who regularly appropriated stylized male haircuts.13 Further, by dying their shorn hair pink or green and donning outlandish clothing and eye makeup, Cahun pronounced their misfit with the norms of gender or sexual minority subcultures around them. Even the radical artists and writers close to Cahun were sometimes unsettled by their indecipherability. In 1933 Pierre Caminade described Cahun as “the bizarre, the bizarre made into a woman, a kind of lightning strike by surreality.”14 Cahun’s defiance of the terms of gender’s legibility apparently challenged the bounds of decorum, even for those who countered the tastes of their era.

Living shamelessly out of step with the world around them, Cahun signals how interwar European trans nonbinary identity might have configured embodiment as a rejection of biopolitical power. Cahun and Moore’s artistic and political lives were closely tied—becoming increasingly so with the rising threat of fascism—and they joined several Surrealists in the Association des écrivains et artistes révolutionnaire (Association of revolutionary writers and artists)in 1932. Cahun linked sexual and gender liberties to struggles against racist oppression, writing that maintaining one’s freedom of expression and lifestyle was critical to opposing Hitler and fighting for “the rights of the human being oppressed by centuries of ferocious superstitions.”15 The couple continued their artistic and political resistance while living on the Isle of Jersey under Nazi occupation during the Second World War. Disguising themselves as innocuous heterosexual women, they covertly encouraged German soldiers to defect for several years until they were discovered in 1944 and imprisoned, and their life’s work largely destroyed.

Given the Nazis’ suppression of gender and sexual deviance and so-called degenerate art, the works destroyed by Nazi soldiers may well represent more radical deviations from sexual and gender norms than the photographs that survived. However, the extant staged portraits and photomontages made while the couple lived in Paris show that Cahun and Moore queered photography’s indexicality in unprecedented ways. They regarded the camera as just one element of an expanded photographic process which consisted of endless iterations of costuming, posing, shooting, cutting, and montaging in an effort to theorize the reality of trans selfhood against a void of contemporaneous language and role models.

Touching Claude Cahun

The fragmentary shape of archival accounts of queer and trans lives requires a range of historical practices for recuperating queer subjects whose identities cannot be absolutely confirmed by contemporary epistemological frameworks for gender and sexuality. The notion of queer, cross-temporal “touches” describes how contemporary recognition of queer historical figures can compose lived relationships between queers of past and present.16 Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick describes this relation of touch as “touching feeling,” summoning the immediacy of the corporeal and emotional senses implicated in the hunt for queer history.17 Feeling suggests permeability where there is supposed to be boundary; glue where one looks for separation; discovery of the self in the other; losing track of the other in the self. To that (unending) end, the feeling touch across time is an embodied, affective coemergence of queer subjects in which one finds that somehow, as implausible as it seems, time must have turned to matter because distinctions between oneself now and an other then prove unentanglable. In this way gender variance in the past threads through the fabric of queer subjectivity in the present. Likewise, stray filaments of queer lives flecking archives of times where one thought they were not suggest a dissipated queer emergence strung through time with no bounded moment of origin.18 This kind of temporal touch fingers that sticky slippery, handle of the nature of trans itself: a subjectivity which is at once a permanent feature of gendered sociality but also never fixed.

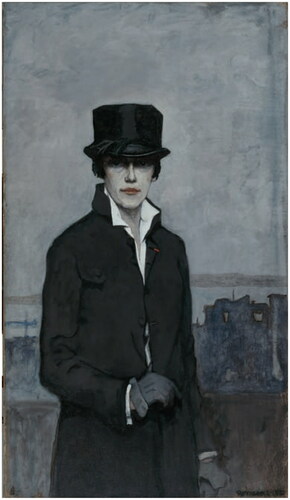

Filling absences left by the heteronormative archival gaze is thus not simply an episode of correcting history but also of queer identity’s becoming in the present and future. Introducing Women Together/Women Apart (2005), which documents Cahun and Moore’s lives along with interwar Parisian lesbian artists, Latimer names such a queer temporal touch which began as a “shock of recognition” during her youth and remained alive as the kindling for her later research into unaccounted-for lesbian histories. As a young person encountering Romaine Brooks’s Self-Portrait in a museum, Latimer recognized “my kind of woman” in the masculine attire and insolent stance of the painting’s subject.19 “Not needing confirmation from the wall text (which offered none in any event),” Latimer felt a sense of recognition that instilled in her an “awareness of alternatives to the scenarios of marriage and motherhood that shaped a woman’s destiny” otherwise unimaginable from the perspective of her postwar suburban upbringing. Filling in the gaps of the heteronormative archival gaze with queer, cross-temporal recognition supplied Latimer with “unnamed potential, unimagined horizons of possibility” that made her own queer life livable in the absence of living role models.20 Though the portrait was merely a fragmented suggestion of a gender-nonconforming life without proper account, that encounter pressed Latimer onto a previously unthinkable life path.

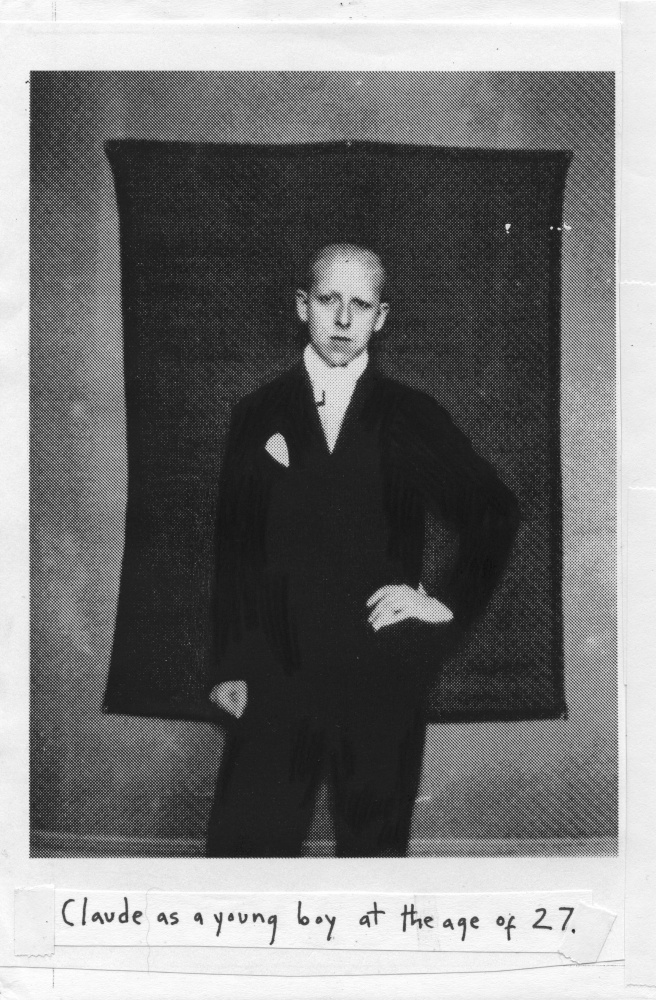

A similar shock of recognition was recorded in a touch shared between Cahun and trans activist artist Micah Bazant on the heels of the first appearances of Cahun’s work in the United States. Encountering a portrait of Cahun in the New York Guggenheim’s Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose: Gender Performance and Photography exhibition catalog (1997), Bazant presented a trans counterreading of Cahun in their widely distributed underground zine, Timtum: A Trans Jew Zine (1999).21 Bazant describes Cahun as a yearned-for role model who lived a gendered embodiment “different in ways that had [and] have no name.”22 Cutting, pasting, and photocopying Cahun and Moore’s photographs into their zine, Bazant recontextualized Cahun as a historical mirror for a “fabulously different” gender identity, captioning one portrait “Claude as a young boy at the age of 27.” The portrait of Cahun bears striking resemblances to Brooks’s. Each figure dons the masculine attire and swishy gestures of a dandy. However, Brooks’s eyes, shadowed by a top hat, and upturned collar suggest that she is poised to blend in as she descends into the city nightlife. She is in masculine disguise. In contrast, Cahun is decidedly conspicuous. Their shaved head is sharply defined by its stark, tonal difference from the black backdrop. Cahun does not blend in. Unlike Brooks’s shaded gaze, Cahun’s taunts the camera in repudiation of both conformity and shame. Echoing Latimer’s gaining a sense of life’s possibility when finding her kind of woman in Brooks, Bazant claims Cahun as their kind of boy to legitimate alternatives to male and female embodiment yet unnamed in the 1990s. Published at the horizon of the rise of nonbinary trans identities, Bazant’s portrait pairs “young boy” with “age of 27” to indicate both the common age misrecognition of trans people and the idea that boyhood is not so much an indicator of youthfulness as a gendered status lying somewhere between androgynous childhood and manhood. “Sometimes boy feels like a revolutionary new gender”; Bazant explains their ambivalence about the potential of the label “boy” as meeting the need for language to describe people like themself. “Sometimes . . . it’s the closest choice I got.”23 Cahun’s appearance affirms Bazant’s felt sense of self in the absence of role models during their historical present.

Bazant’s zine refutes the claim that it is new to identify Cahun as trans, instead attesting to the simultaneous divergent reading of Cahun and Moore’s archive through cross-temporal touches that make untenable a clear accounting of the distinctions between trans identities of the past and present. Bazant forcefully revises the archive’s cisnormative account of Cahun, reproducing and altering texts from various 1990s monographs on a page titled “Claude Cahun: Jewish genderfreak anti-Nazi resistance fighter.” Where Rosalind Krauss finds the chosen name “Claude” as evidence of “parading one’s lesbianism,” Bazant sees a reflection of their own gender-neutral name, intended to encourage people to “see me beyond my gender.”24 Bazant adds “trans gender” to descriptions of “lesbianism.” They selectively alter art historians’ use of pronouns to create gender-anomalous statements, such as “he surrounded herself” and “she adopted a mask of masculinity that he further exaggerated.”25 Interleaving Cahun’s biography and images with Bazant’s personal narratives of transition, Jewish identity, drawings, trans educational resources, Jewish histories, and queered Yiddish language definitions, Bazant draws Cahun into a text designed to contribute to building shared possibilities for trans life for those who cannot find their way in FTM/MTF identities. Troubling distinctions between trans past and present, Cahun’s portraits appearing in the zine can be regarded as one of many touches belonging to efforts in the 1990s and 2000s to unleash “trans” and “transition” from transsexual medicine’s assumptions about gender.26

Bazant and Cahun’s touch is not merely an essentialized (mis)recognition constructed between gender-nonconforming people that elides differences between their historical contexts but more precisely a recognition between those unable to locate themselves on the incomplete map for gendered life particular to their own eras. In one frequently cited quotation Cahun states, “Masculine? Feminine? That depends on the occasion. Neuter is the only gender that invariably suits me. If it existed in our language one would not observe this oscillation in my thinking.”27 The 1990s authoring of Cahun’s biography as female has caused art historians to persistently read such statements either as Cahun’s refusal to occupy a stable authorial subjectivity or as related to the period term “invert,” which described homosexuality as expressing an inverted gender identity. While the latter reflects the sexological literature of Cahun and Moore’s era, the former reproduces that literature’s problematic assumption that subjectivity can only be stabilized within male or female gendered embodiment, failing to recognize that Cahun’s stated identification as neuter (neutre) contradicts such a cross-gender notion of inversion. Although trans identities that claim their ontological condition to existence in the negative—such as nonbinary, gender nonconforming, and agender—seem to meet Cahun’s stated desire for an alternative to the masculine–feminine binary, art historians have cautioned against reading Cahun in terms of the “fluidity” of “postmodern” identity categories, eliding embodied and lived trans identities with the postmodern tendency to detach surfaces from substance.28 Implications that trans people are a new “phenomena” who do not preexist language to describe them grants dominance to 1950s transsexual medicine for “inventing” trans people who are “constructed” by doctors rather than ontologically gendered in the way cismen and ciswomen are believed to be.29 The mistake here is, on the one hand, the assumption that “man” and “woman”—and likewise “lesbian”—enjoy a historical stability which “trans” uniquely lacks.30 On the other hand, it mirrors the very constraints placed upon gendered life which Cahun actively defied. There is no reason to assume that Cahun and Moore did not work for legitimation of gendered subjectivity believed impossible during their time. In fact, everything about their oeuvre suggests they did.

Turn-of-the-century sexological discourse theorized that same-sex desire resulted from cross-gender identification, first referred to as “inversion” by sexologist Havelock Ellis in 1897. Cahun’s translation of Ellis’s writings into French and familiarity with the work of his predecessor German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s work is frequently cited as evidence that Cahun likely understood their gender variance in terms of sexuality.31 However, Jay Prosser’s analysis of sexologists’ case studies demonstrates that the term “invert” originally indicated trans identity rather than sexual identity, which characterized the bulk of the autobiographical narratives they studied.32 “Homosexual” erroneously replaced “invert” following Sigmund Freud’s reauthoring of trans autobiographical accounts in terms of momentary gender identifications experienced en route to fixed sexual-object choices. Ellis was himself undecided on the issue and critical of Freud’s heavy-handed revisions as signaling a mistrust of the authenticity of patients’ experience. Diverging from Freud, Ellis’s Psychology of Sex (1933) continued to explore gender as a mutable spectrum unlinked from biology and sexuality.33 However, Freud’s revisions had already marked an aggressive turn in the sexological literature toward largely studying and explaining sexuality rather than gender identity, leaving a void in psychological discourse that would not be filled until the term “transsexual” emerged in the 1950s as an object of medical discourse whose treatment involved somatic rather than psychological intervention.34 Meanwhile, as Julian Gill-Peterson and Kadji Amin document, this same period was also the “glandular era” of eugenicist medical discourse, during which intersexuality, transvestitism, and homosexuality were attributed to “disorders” of testes and ovaries. Ambiguously gendered people were subjected to invasive surgeries and visual technologies which sought to discover their “true” sex and correct errant characteristics.35 The assumption that a stable male or female gender identity could be found within the mind or body therefore characterized psychological and medical discourses during Cahun’s lifetime.

In contrast, Cahun and Moore’s engagement with sexological literature demonstrates not only resistance to the conflations of gender, sexuality, and biology of their era but insistent attempts to touch the trans possibilities of the era prior, tracing the same steps Prosser would later recover. Cahun and Moore became familiar with sexological discourse as teenagers. In their first collaboratively authored text, “Les jeux uraniens” (The uranian games, ca. 1913), the couple employed the term “uranian” (uranien), a literary reference to Karl Heinrich Ulrichs’s writing in 1860s Germany.36 Though uranian is frequently understood in terms of Ulrichs’s later reputation as an advocate of homosexuality, the term was in fact part of Ulrichs’s project to categorize a spectrum of subjectivities relating to trans and homosexual experience. “Uranian” described his own experience as “the soul of a woman enclosed in a man’s body.”37 Krafft-Ebing drew upon Ulrichs’s account to theorize “inverted sexual instinct” as a cross-gender condition that sometimes but not always accompanied homosexuality.38 “Les jeux uraniens” also quotes homosexual playwright Oscar Wilde, famously convicted of “gross acts of indecency” in 1895, whom Cahun frequently emulated in their dandyish public appearance. Elizabeth Freeman aptly describes such embodiments of past identities as “temporal drag,” indicating how the weighty tug of history informs queer gender performance in the present.39 I propose that this queer temporal “feeling backward” of Cahun and Moore’s early collaborations resonates throughout their oeuvre.40 By locating their own identities along twisted, biotemporal routes through the subjectivities of nineteenth-century trans women and effeminate men, Cahun and Moore cobble together the possibility of a trans nonbinary subjectivity out of queer, cross-temporal touches. Their oscillations between past and present theorize trans selfhood by eliciting an unnamed chasm beyond discreet categories of male and female, body and mind, interior and exterior—posing incontrovertible resistance to twentieth-century scientific discourse’s attempts to stabilize biological sex within such binaries.

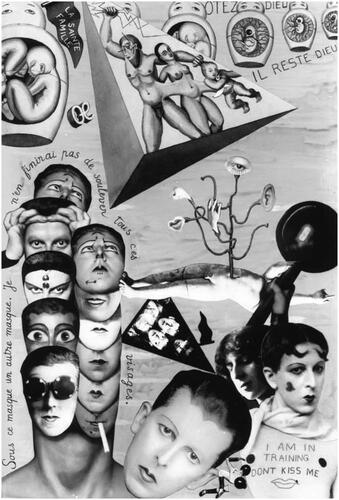

Seeming to mock both psychoanalytic and intersex medical discourses, which wielded an array of tools from X-rays to dreamwork to find the facts of sex within the gender-variant subject’s interior, the couple’s later turn to photomontage posits photography as a parallel surgical technology of corporeal and psychic invasion. In one 1930 photomontage from Disavowals; Or, Cancelled Confessions, Cahun looks directly into the camera lens, a montaged pistol pressed to their temple, merging gun and camera “shots” to suggest that only death will finally make available the “truth” of the body’s interiority. Flayed by camera and scissors, Cahun’s surreal entrails spill onto the darkroom’s operating table—four sets of ribs, human parts merged with bird parts inside and out, headless bodies, bodyless heads, and skinless faces. A scissor-severed beak (left) is the silenced voice of an illegible creature, while lips (right) part to reveal a hand in place of a tongue—an illegible body-voice. Cahun and Moore draw attention to the impotence of language to describe this mess of interiors and exteriors, species and genders. The montage flies in the face of science by exposing Cahun’s interior as an interminable hall of mirrors where every interior “fact” turns out again to be a monstrous exterior construction. Cahun writes that though the “surgical blade” expects to “encounter an ivory core” within its subjects, what it finds is “just rubbish, rubbish, piles of rubbish all the way into its unrecognizable center.”41

In contesting fallacies regarding the gender-nonconforming subject’s interiority, Cahun cracks the backbone of myths about so-called biological nature. The final photomontage of Disavowals; Or, Cancelled Confessions postulates that “facts” about the vitality of heterosexuality are equally imaginary. Multiple iterations of Cahun’s own face tower one on top of another to form an erect phallus climbing toward the heterosexual ideals that float above. The Russian dolls incubating fetuses and the tetrahedron-encased nuclear family parade the perfection of clone-like, clockwork procreation. The flag reading “La Sainte Famille” (the Holy Family) announces the father–mother–son trinity as a “triple-faced monster” of French nationalist fantasy.42 In contrast to the heterosexual pair who breed just one future patriarch, Cahun is arguably more fecund. They propagate seventeen heads from their own flesh. The text sheathing the Cahun-faced phallus reads: “Under this mask, another mask. I will never finish removing all these faces.” They suggest that the vigorous drive for self-knowledge is behind their prolificacy. In contrast, the hardy biological facts of sex appear to be at an evolutionary disadvantage here, overidealized to the point of emptiness. The camera’s “mechanical reproduction” is posited as a politically radical technological alternative to heterosexual procreation.43 A few pages after the montage appears they describe posing for the camera as a means to “make my own vocabulary” with which to “divide myself to rule myself, multiply myself so I can make my mark.”44 Cahun’s masks pile a lexicon of poses against the gaping chasm unchartered by the sexological discourse of their present.

They heap photographic index upon index upon index as if to point all fingers and facts at a way of being that feels existentially real yet remains unrecognized in interwar France. In a photographic temporal reach of snaps and skips that rivals the biological time of child-bearing reproduction, Cahun’s masks pitch the radical possibilities of gendered pasts against the void of the present with a plunk that resounds within the cavernous remains of a posttranssexual future. In other words, these photographs bear fruits.

Bit by the Guillotine Mirror

It is perhaps precisely because Cahun’s montaged bodies bear little resemblance to those typically associated with trans embodiment and cannot be interpreted as literal surgical interventions that their work is an invaluable contribution to histories of the trans somatic imaginary. Their inexhaustible corporeal transformations theorize trans as the constant surfacing of gender formations which refuse fixity (remarkably prescient of medical perspectives that legitimize the fluidity of one’s gender identity over time and which remain marginalized within trans healthcare today).45 Cahun breaks the facticity of the photograph and the legibility of the body alike to conceptualize a trans corporeal transformation unhinged from the indexicality of the sexed body. In a passage opposing the divvying of the self into psychoanalytic “drives” and medicalized “glands” they gesture to an interior sense of self that has no indexical counterpart:

When the mechanism has been completely deconstructed, the mystery remains intact. Sometimes chance hands us a little swatch of soul. We put it away in a drawer. Soon it will be impossible to match it with the piece of fabric it originally came from.46

Cahun’s carefully preserved fragment of true self has no body or name into which it might settle to compose a stable fit between signifier or signified.

Cahun’s photographic process is not that of seeking to describe the swatch of soul more accurately—for that would make it the subject of the diagnostic gaze—but to make it the active agent of personal transformation. Speaking again to the sacred fragment, they declare, “live and grow in me, he she—or simply it—that allowed me, still young, to understand that I should only, because I can only, connect with, change myself.”47 The text brims with a constant desire to alter the body, “change skin,” “metamorphose,” “transform,” and sever body parts:

If an element doesn’t fit my composition, I leave it out. One thing after the other, I eliminate everything . . . . I shave my head, pull out my teeth, remove my breasts . . . everything that perturbs or waylays my regard: the stomach, the ovaries, the mind, conscious and cyst-bound.48

In a slippage between artistic process and body modification, Cahun cleaves body and psyche until only the heartbeat remains as a final achievement of “perfection.”49 The impulse to remove breasts and ovaries in order to appease their discomfort conforms to contemporary diagnoses of gender dysphoria and the surgeries prescribed to assuage it. However, their wish to lop off flesh and bone until only the bare condition of life remains exceeds any plausible interpretation of gender dysphoria or transition. Today Cahun’s narrative would not be rubber-stamped by doctors who continue to require patients to articulate standardized “wrong body” narratives to obtain authorization for medical transition. Their gender can neither be pinned to the sexed characteristics of their embodiment nor cured by surgical intervention, instead expressing the desire for a trans “embodied difference” that conceptualizes “genders as potentially porous and permeable spatial territories.”50 Guided by self-knowledge in opposition to normalizing discourses, theirs is a trans corporeal transformation that neither “lands” in a stable and legible embodiment nor pathologizes that fact. They engage in a somatic becoming that has no prescribed end point.

Specific attributes of photographic technology supply Cahun the power to radically embody their difference as the refusal of gender fixity itself. The camera’s ontological mode of record making is a cut. It severs a framed slice of the visible surface of reality from its lived substance and temporal fabric. Cahun accordingly calls the camera a “guillotine window”—an antiquated reference to the blades of the camera shutter, which for Cahun emphasizes the fatal laceration of the body. They describe adding silver to the guillotine window—a reference to the backing of a mirror and also the grains of light-sensitized silver in photographic film and paper—which makes the photographic apparatus double as window and mirror, positioning Cahun and Moore each on either and both sides at once.51 Similarly, they name the camera’s lens “our double eyelid.”52 It is the gateway to the hall of guillotine mirrors. The lens both sees the visible surface of the world and also projects it inward to the camera’s dark interior so that one might behold at once the swatch of soul and the fabric of reality.

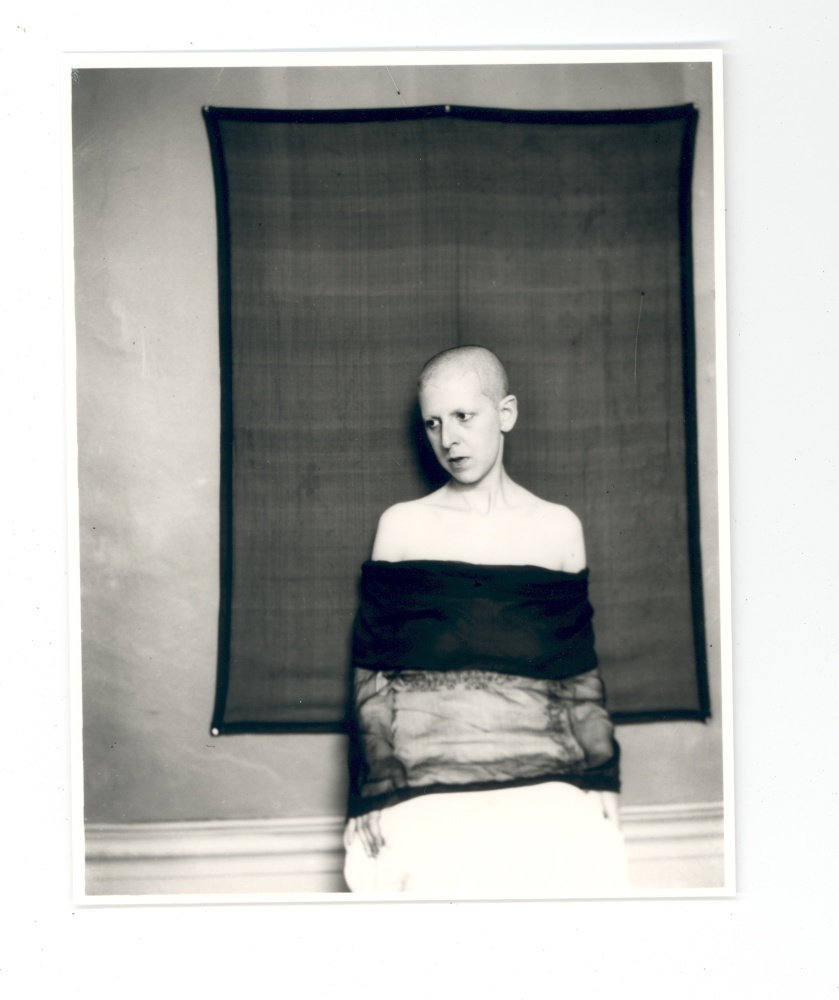

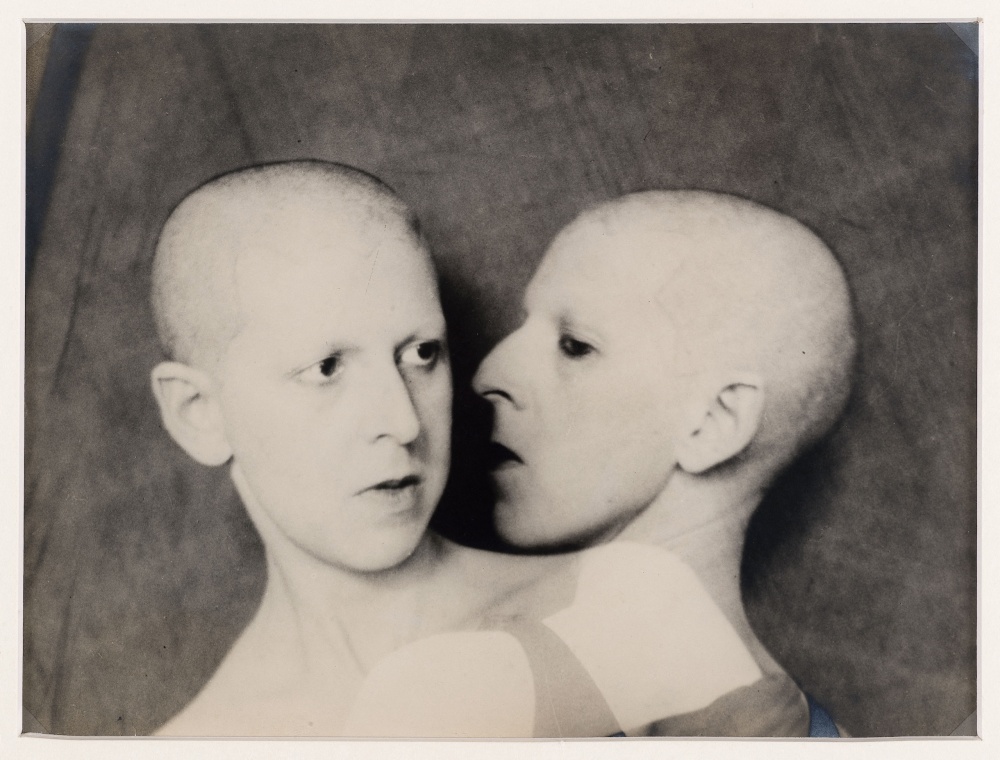

The photographic “cut” also fits well with Cahun’s frequent references to masks and unmasking. The meaning of the word “mask” (masque) also refers to the darkroom technique (masque photographique) of blocking the exposure of select areas of an image. Cahun and Moore apply this kind of photographic masking to make photomontages both in the darkroom and in the studio, where black cloth blocks out areas of the body or environment. Photographic masking techniques allow them to “unmask nature” by turning the body into mere surface, severed from somatic experience. In one untitled pair of photographs, Cahun appears against a dark backdrop that has been temporarily pinned to a wall, revealing the self-conscious construction of images that were likely not intended to be exhibited full frame as they appear here. Cahun wears a dark cloth wrapped around their chest and arms. The dark background and clothing mask the body and room to perform the first cut of the guillotine mirror, making Cahun’s body appear to float in a void to enable later montaging and composite printing. The blackness around Cahun’s figure becomes the nonplace of blankness that obscures the difference between the material background of the homemade studio, the blackness of the camera’s interior, the darkness of the darkroom, the negative space of the collage, and the inner conscience of photographer and subject. From the moment of exposure, the image refracts through lens, eyelid, and mirror into multiple darkened spaces of camera, darkroom, montage, and psyche. Cahun is thus both masked (photographically cut) and unmasked (shorn of gender signifiers). Masking produces a slippage between reality and image, interior and exterior. Cahun’s figure turns from real to mask, from photographic trace to stray phantasm, from tangible signifier to inner sensation.

Once Cahun and Moore make a photograph, it becomes part of their narrow repertoire of images to be repeatedly recycled and reconfigured. No amount of masks ceaselessly refracting through a hall of guillotine mirrors can settle the question of the identity of Cahun’s swatch. The mirrors instead bring us into the heart of the dysphoric interior–surface tangle of the trans nonbinary subject’s embodiment. In “Bedroom Carnival” (Carnaval en chambre, 1926) Cahun describes the accumulations of masks both “carnal” and “verbal” acquired in the course of growing up:

I had spent my solitary hours disguising my soul. The masks had become so perfect that when the time came for them to walk across the plaza of my conscience, they didn’t recognize each other. I adopted the most off-putting opinions one by one, those that displeased me the most had the best chance of success. But the make-up that I employed seemed indelible. I scrubbed so hard to wash it off myself that I took off my skin. And my soul, like a flayed face, no longer had a human form.53

Cahun recalls a lifetime of assembling a false persona calculated as the perfect disguise for a self who had no chance of surviving by the gender norms of the society into which it was born. As many scholars have already pointed out, such statements anticipate Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity in which the child’s gradual accrual of gestures, habits, and appearances which match their assigned gender eventually creates the illusion that gender naturally emanates from the sexed body rather than having been externally imposed.54 However, Cahun’s effort to scrub all masks away also describes the trans nonbinary subject’s horror at discovering the impossibility of returning to a “pure” embodiment untouched by gender. The desire to touch a past only sensible inside the self points to aspects of gender Butler overlooks: that gender performance is not so much characterized by the emptiness of copied copies but by the earnestness of turning temporally backward to feel around for the original left behind.55 This search is inevitably belated. By the time one discerns their appearance as merely a clever facade, the false exterior has indelibly inked the interior. Cahun is haunted by the sense that another self was once possible. What such a self might look like, however, remains beyond the human imaginary of their time.

In light of this revelation Cahun’s statement, “Under this mask, another mask. I will never finish removing all these faces,” reveals another meaning: the exhaustion brought about by the interminable labor of self-determination. Cahun will never catch up with the damage done by once having tried to find their way by norms of recognition. Carefully assembled for survival in the social world, Cahun’s masks are not solely cultural symbols that circulate outside in the social world of signs but penetrate within, parading across the plaza of the conscience in place of the true self. Try as one might, surface cannot be scrubbed from substance. As Cahun states, “You apply your mask too heavily, and it bites your skin. . . . You realize with horror that the flesh and its cover have become inseparable. Quick, a little saliva; you reglue the bandage to the wound.”56 Here the slippage between bandage and mask, self and wound, is telling of the trans experience. Gender performance is not merely a thing of theatrics and play but a means of survival which forever alters “the unique unnamable” self.57 The always-already quality of the mask that both wounds and bandages indicates the precarity implicated in Butler’s theory of gender performativity: the fact that one is born into a gendered order not of one’s choosing by which one must abide to gain the support necessary to sustain human life.58

To engage in surgical self-discovery that peels away the bandage-mask is to reveal a fragmented, nonhuman soul ravaged by its own carnival masks. What Do You Want from Me? (Que me veux-tu?), a composite version of the untitled 1920 portraits, manifests the impossible “flayed face” of Cahun’s interiority. Finally shorn of every accrued affectation and gendered signifier, Cahun’s self is unrecognizable by frameworks for human life. Cahun gains no power through the loss of gender signifiers. Their shaved head and nude torso represent power and identity commonly stripped from prisoners and the institutionalized. The paired front and side views evoke the police mug shot. The merged torsos are suggestive of conjoined twins, who were subjects of popular and medical fascination during the era. All of these suggestions reference a loss of power by those ejected from frameworks of the human.59 However, as bodies photographically superimposed upon one another, Cahun’s self-image is also an impossible human—a figment of the psyche who cannot exist in the somatic world. It is the darkroom that allows Cahun to finally meet themself. Cahun’s faces simultaneously examine and avoid each other. They find themselves stuck together yet unable to recognize one another. As the title suggests, the longed-for encounter with the soul is an unwelcome intrusion. The composite image reveals the stakes of recognition for the trans nonbinary subject. On the interior side of such a failure of recognition is the fact that those who cannot settle into male or female subjectivity, lacking language or images to describe such people, come to believe they are impossible and mad. On the exterior side of this failure of recognition, those who fail to pass as male or female are jettisoned from the realm of the human. This utter failure renders the wound and bandage mask as one and the same.

Their theorization of gender utilizes the limits of photographic technology to speak to the limits of the body to make apparent one’s sense of self. Even a “straight” photograph constructs that which it appears only to record as natural fact—subjected to so many cuts in the process of making that its relationship to any factual reality is profoundly tenuous.60 Cahun’s use of photography draws parallels between the fallibility of the photograph’s indexical function and the body’s. Mangling facts, fictions, bodies, and genders to stretch the elasticity of photography to its limit—its inescapable tie to the visible—Cahun points to the limits of the body to make visible the sense of a self for whom any externalization invites the diagnostic gaze. They sentence that gendered surface of the body to death by guillotine mirror. “What would be the use of pulling the lid off such mysteries?” Cahun asks. “So that the mechanism appears? Too late for us, body and soul beyond repair.” Every time we think we have seen it, it turns out again that our belated gaze meets mere surface, “useless as Mona Lisa’s smile, trompe l’oeil painting. Impenetrable facade.”61 Even a proliferation of discourse to make the self legible—“truths that stick out a mile”—can only form an illusory self-image “painted in trompe l’âme.”62 Such an image tricks not the eye, but the soul (l’âme).

Trans on This Side of the Overthrow

In distinction from the transnormalizing effects of 1950s transsexual medicine, Cahun and Moore’s cuts with the guillotine mirror are not invested in mainstream cultural legibility for trans subjects. They theorize the potential of the gender-nonconforming subject to rupture the bounds by which human life is defined, anticipating trans as a political identity of radical illegibility distinct from diagnostic discourses. Cahun and Moore forge a precedence for the notion that “trans” might signify not so much a complex space between “man” and “woman” but instead the space between the body and the biopolitical state—from which profoundly new possibilities for social life materialize.63 Cahun is anything but the “good transsexual” upon which transsexual medicine and the normalized “spectacular whiteness” of trans identities would be built after the war.64 Instead, Cahun believed they had a revolutionary duty to “embody my own revolt” as a contribution to struggles against patriarchal power.65 By living the political revolt of the revolting (révoltant), Cahun and Moore claimed a space for recognition for the unrecognizable.66 Their photographs theorize trans embodiment as a wrench in the registers of biopolitical power.

However, rather than narrate Cahun and Moore into a “trans-before-trans” origin teleology, identifying their gender as politicized necessitates situating them within the turn toward public legibility of contemporary trans identities, which was achieved by negating correlations between white transsexuals and gender variance in Black and Indigenous peoples.67 b. binaohan points out that the politicization of trans identity that arose in the 1990s in distinction from medical discourse mirrored the same colonial history of gender variance.68 “New” white, middle-class, trans politics proved hostile to and ignorant of political organizing by trans women of color. binoahan cautions against the articulation of a coherent historical trans community because of the incessant potential to recreate terms of recognition that exclude trans women of color from frameworks of the human.69 The legitimized public visibility of white subjects who “invent” transsexuality and its politicization creates a temporal facade by which white trans histories appear to precede Black and Indigenous histories in what C. Riley Snorton identifies as another iteration of Homi Bhabha’s concept of colonial-mimicry narratives. By continually displacing colonial subjects as behind whites, nonwhites are produced in public discourse as a parroting Other.70 Writing whites into trans history as protopoliticized nonbinary trans subjects risks substantiating such chronobiopolitical illusions—the kind of trompe l’âme masquerading as “truths that stick out a mile” against which Cahun warned.71

We might thus situate the backward feeling touch between Cahun and 1990s trans and lesbian cultures as arm-in-arm skips back and forth across a selfsame void—that fraught colonial fabric within which gender freedoms are selectively doled out as a racial privilege—rather than as a reach across two voids temporally separated by the advent of transsexuality. In fact, Cahun appears to situate their embodied revolt in a present unbroken from our own:

I had always admitted that in a new world there would no longer be a place for iconoclasts of my kind and not being able to glimpse what future would be waiting for me on the other side of the overthrow . . . my role was to embody my own revolt and to accept, at the proper moment, my destiny whatever it may be.72

The politics of Cahun’s gendered life are so relentlessly emergent that they readily anticipate their own undoing. They foresee the successful outcome of their embodied noncompliance as the eradication of the bourgeois entitlement which permitted their public life as a “bizarre” gender misfit in the first place. With such a destiny still unrealized, Cahun therefore suggests that we occupy this “side of the overthrow” with them—feeling backward for something irrevocably lost—rather than that today’s nonbinary trans identities actualize Cahun’s desired future of freedoms not yet imaginable.

This is made strikingly apparent in twenty-first-century celebrations of Cahun’s gender transgressions within Israel and Israeli-funded art institutions that pinkwash queerness as exemplary of the gender freedoms protected by the settler-colonial nation against the backdrop of Palestinian dispossession and genocide.73 While contemporary frameworks for acceptance of trans people appear to expand the definitions of human life, they must be situated within increased global precarity that in fact suggests the valuation of human life narrows when the nation-state lays claim to gender’s temporal “progress.”74 That Cahun lost their life to the fight against genocide demonstrates that twenty-first-century legibility is not the resolution they sought but another trick, requiring more exhaustive mask-scrubbing labor. What (unending) end have Cahun and Moore yet to meet in the backward emergence of trans liberation?

Jordan Reznick is a Getty/National Endowment for the Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow at the Getty Research Institute. They are working on a book project entitled “Landing the Camera: Indigenous Ecologies and Photographic Technologies in the West.”

I thank Tirza True Latimer, Micah Bazant, and Julian Carter for their insights, feedback, and support. I am also indebted to the anonymous reviewer who discovered a latent field of possibility waiting to be pulled to the surface of the text.

- Abigail Solomon-Godeau, “The Equivocal ‘I’: Claude Cahun as Lesbian Subject,” in Inverted Odysseys: Claude Cahun, Maya Deren, Cindy Sherman, ed. Shelley Rice (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), 111–26; and Tirza True Latimer, Women Together/Women Apart: Portraits of Lesbian Paris (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2005). ↩

- Tirza True Latimer, “‘Le Masque Verbal’: Le Travestisme Textuel de Claude Cahun,” in Claude Cahun, ed. Juan Vicente Aliaga and François Leperlier (Paris: Éditions Hazan, 2011), 81–82. ↩

- Christy Wampole, “The Impudence of Claude Cahun,” L’esprit créateur 53, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 101–4. ↩

- Susan Stryker, Transgender History: The Roots of Today’s Revolution, 2nd ed. (New York: Seal Press, 2017), 45–46; and Julian Gill-Peterson, Histories of the Transgender Child (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018), 8–16. For examples of trans and nonbinary historical figures and methodologies for identifying them, see Judith Halberstam, Female Masculinity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998); Carolyn Dinshaw, Getting Medieval: Sexualities and Communities, Pre- and Postmodern (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999), 106–12; Rebekah Edwards, “‘This Is Not a Girl’: A Trans* Archival Reading,” Transgender Studies Quarterly 2, no. 4 (November 2015): 650–65; Leah DeVun and Zeb Tortorici, “Trans, Time, and History,” Transgender Studies Quarterly 5, no. 4 (November 2018): 518–39; Julian Gill-Peterson, “Trans of Color Critique Before Transsexuality,” Transgender Studies Quarterly 5, no. 4 (November 2018): 606–20; and Allison Surtees and Jennifer Dyer, eds., Exploring Gender Diversity in the Ancient World (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020). ↩

- Gill-Peterson, Transgender Child, 10; Edwards, “‘This Is Not a Girl,’” 653. ↩

- Robert Mills, “Visibly Trans? Picturing Saint Eugenia in Medieval Art,” Transgender Studies Quarterly 5, no. 4 (November 2018): 541. ↩

- Claude Cahun, Disavowals; Or, Cancelled Confessions, trans. Susan de Muth (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), 151–52, 200. ↩

- Dinshaw, Getting Medieval, 106. ↩

- This queer archaeological method is suggested in Halberstam, Female Masculinity, 50–51; and Heather Love, “Spoiled Identity: Stephen Gordon’s Loneliness and the Difficulties of Queer History,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 7, no. 4 (2001): 487–519. ↩

- Cahun, Disavowals, 12. ↩

- Ibid., 102–3. ↩

- Latimer believes Cahun was introduced to Havelock Ellis’s Psychology of Sex while volunteering at Sylvia Beach’s bookshop in Paris, where Beach displayed all six volumes prominently (Latimer, Women Together, 9–17). In France the name “Claude” is used for both men and women, while “Marcel” is typical for men; they adopted the names “Claude Cahun”and “Marcel Moore” as teenagers during the same period that Cahun’s personal snapshots show they began to shave their head and reject feminine attire; see Jennifer L. Shaw, Exist Otherwise: The Life and Works of Claude Cahun (London: Reaktion, 2017), 26. ↩

- Latimer, Women Together, 26–28. ↩

- François Leperlier, Claude Cahun: L’exotisme intérieur (Paris: Fayard, 2006), 219–20, 247 (emphasis in original). ↩

- Ibid., 377–80. ↩

- DeVun and Tortorici, “Trans, Time, and History,” 518–39; and Carolyn Dinshaw, Lee Edelman, Roderick A. Ferguson, Carla Freccero, Elizabeth Freeman, Judith Halberstam, Annamarie Jagose, Christopher Nealon, and Nguyen Tan Hoang, “Theorizing Queer Temporalities: A Roundtable Discussion,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 13, nos. 2–3 (2007): 177–95. ↩

- Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 6, 17–18. ↩

- Love, “‘‘Spoiled Identity,’” 496–97. ↩

- Latimer, Women Together, 1 (emphasis in original). ↩

- Ibid., 1 ↩

- Jennifer Blessing, Rrose Is a Rrose Is a Rrose: Gender Performance in Photography (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1997). In a conversation with Micah Bazant, they stated that though it is difficult to estimate the distribution of the zine because of its reproduction and distribution by readers, Bazant estimates that a minimum of 2,000 paper copies were distributed in the first decade after its publication. By 2010 TimTum became available on the QZAP Zine Archive online, where it continues to gain a following; see https://archive.qzap.org/index.php/Detail/Object/Show/object_id/408. ↩

- Micah Bazant, TimTum: A Trans Jew Zine (n.p.: printed by the author, 1999). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid.; and Rosalind E. Krauss, Bachelors (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), 42. ↩

- Bazant, TimTum (emphasis in original). ↩

- Benjamin T. Singer, “Trans Art in the 1990s: A 2001 Interview with Jordy Jones,” Transgender Studies Quarterly 1, no. 4 (November 2014): 620–26. ↩

- Cahun, Disavowals, 151–52; this translation is suggested by Latimer, Women Together, 101. ↩

- Danielle Knafo, In Her Own Image: Women’s Self-Representation in Twentieth-Century Art (Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2009), 56. ↩

- Gill-Peterson, Transgender Child, 11–13; and Jay Prosser, Second Skins: The Body Narratives of Transsexuality (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 7–9. ↩

- Susan Stryker and Aren Z. Aizura, “Introduction,” in The Transgender Studies Reader 2, ed. Stryker and Aizura (New York: Routledge, 2013), 6. ↩

- For example, Shaw, Exist Otherwise, 67–72; and Havelock Ellis, La Femme dans la société, vol. 1, L’hygiène social: Études de psychologie sociale, trans. Lucy Schwob (Paris: Mercure de France, 1929). Cahun also translated volume 2 of Ellis’s text, but it was never published (Latimer, Women Together, 171n64). ↩

- Prosser, Second Skins, 135–55. ↩

- Havelock Ellis, Psychology of Sex: A Manual for Students (London: William Heinemann, 1933), 195–96. ↩

- Prosser, Second Skins, 139–52. ↩

- Gill-Peterson, “Trans of Color Critique”; and Kadji Amin, “Glands, Eugenics, and Rejuvenation in Man into Woman: A Biopolitical Genealogy of Transsexuality,” Transgender Studies Quarterly 5, no. 4 (November 2018): 589–605. ↩

- Cited in Shaw, Exist Otherwise, 31–32. ↩

- Quoted in Prosser, Second Skins, 143. ↩

- Ibid., 143. ↩

- Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), 61–63. ↩

- On the conception of queerness and its affects as turning back to look at history while looking forward toward a better future, see Heather Love, Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007). ↩

- Cahun, Disavowals, 195. ↩

- Ibid., 191. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Photography in Print: Writings from 1816 to the Present, ed. Vicki Goldberg (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981), 319–34. ↩

- Cahun, Disavowals, 201. ↩

- Julia Temple Newhook, Jake Pyne, Kelley Winters, Stephen Feder, Cindy Holmes, Jemma Tosh, Mari-Lynne Sinnott, Ally Jamieson, and Sarah Pickett, “A Critical Commentary on Follow-Up Studies and ‘Desistance’ Theories about Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Children,” International Journal of Transgenderism 19, no. 2 (April 2018): 212–24. ↩

- Cahun, Disavowals, 51–52. ↩

- Ibid., 200. ↩

- Ibid., 30. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Susan Stryker, Paisley Currah, and Lisa Jean Moore, “Trans-, Trans, or Transgender?,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 36, nos. 3–4 (2008): 12. ↩

- Cahun, Disavowals, 25. ↩

- Claude Cahun, “Carnaval en chambre” (Bedroom carnival), Ligne de Coeur 4 (March 1926); translated and reprinted in Shaw, Exist Otherwise, 284–86. ↩

- Shaw, Exist Otherwise, 284–85. ↩

- Judith Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” Theatre Journal 40, no. 4 (December 1988): 519–31. ↩

- Freeman, Time Binds, 63. ↩

- Claude Cahun, “Carnaval en chambre,” 285. ↩

- Cahun, Disavowals, 203–4. ↩

- Judith Butler, Undoing Gender (New York: Routledge, 2004), 17–28. ↩

- Judith Butler, Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (London: Verso, 2009). ↩

- John Tagg, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan Education, 1988). ↩

- Cahun, “Carnaval en chambre,” 286. ↩

- Cahun, Disavowals, 201. ↩

- Stryker, Currah, and Moore, “Trans-, Trans, or Transgender?,” 14. ↩

- Emily Skidmore, “Constructing the ‘Good Transsexual’: Christine Jorgensen, Whiteness, and Heteronormativity in the Mid-Twentieth Century Press,” Feminist Studies 37, no. 2 (Summer 2011): 270–300; and Susan Stryker, “We Who Are Sexy: Christine Jorgensen’s Transsexual Whiteness in the Postcolonial Philippines,” Social Semiotics 19, no. 1 (2009): 80. ↩

- Quoted in Leperlier, Claude Cahun, 579. ↩

- Butler, Frames of War. ↩

- See C. Riley Snorton, Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 139–75; and b. binoahan, decolonizing trans/gender 101 (Toronto: Biyuto Publishing, 2014), 69–73. ↩

- binaohan, decolonizing, 70–73; see also Che Gossett and Juliana Huxtable, “Existing in the World: Blackness at the Edge of Trans Visibility,” in Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, ed. Reina Gossett, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017), 42–43. ↩

- binaohan, decolonizing, 70–73; see also Amin, “Glands, Eugenics, and Rejuvenation.” ↩

- Snorton, Black on Both Sides, 157; and Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), 85–92. ↩

- On chronobiopolitics, see Freeman, Time Binds, 3. ↩

- Quoted in Leperlier, Claude Cahun, 579. ↩

- See, for example, Forbidden Junctions and Back to the Canon: Claude Cahun’s Portrait Photographs, exhibition, Israeli Center for Digital Art, Holon, 2008; and Show Me as I Want to Be Seen, exhibition, Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco, 2019. ↩

- Snorton, Black on Both Sides, 7, 143. ↩