Teaching for a Future-Oriented Art History

What are the limits and boundaries of our classrooms? Where and how should our syllabi begin and end? These questions have become increasingly weighty since 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic converged with the longer-standing pandemic of systemic injustice in the US to amply demonstrate that our classrooms are not protected from the upheavals of the world around us. In this series of essays on pedagogy, three art historians (Susan Elizabeth Gagliardi, Yael Rice, and Nancy Um) reflect on classroom experiments—all conducted in 2020, the first year of the pandemic—to expand the purview of the classroom, by inserting into their teaching issues such as ethics, well-being, new research practices, innovations in technology, collaboration, and museum- and collection-based work as fundamental concerns of the discipline. As a group, these three essays, which will appear in succession, consider what the future of the art history classroom might look like, as we face the ever-changing challenges of the twenty-first century.

In fall 2020, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, I taught a collections-based introduction to digital art history for the very first time, via Zoom, at Amherst College, a small liberal arts college located in western Massachusetts.1 Many of the challenges I faced will be familiar to other pedagogues in the discipline, but some were unique to the topic at hand. These included the demands of working closely with museum objects and records; introducing digital skills, tools, and methods; and teaching art historical content—namely drawing from the artistic traditions of India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Tibet—that is unfamiliar to many undergraduate students, all from a seemingly insurmountable physical distance.2 The learning objectives of the course extended beyond those of the traditional art history course to include familiarity with the ethics of data collection, use, and management; data bias; key aspects of museum and curatorial studies; and, of course, digital tools, platforms, and methods for the analysis of museum objects and records.3 The expanded purview of the course reflected the interdisciplinary nature of much art historical teaching in higher education today.4 It also posed very real challenges in terms of balancing region-specific content with art historical, museological, digital humanities, and theoretical approaches.

My idea to offer a course of this kind predated the pandemic, but the rationale to teach it at that particular moment was my response, in part, to the specific learning and living circumstances that the vagaries of the pandemic had thrust upon us. It seemed to me that the remote classroom would offer an apt context in which to explore the distant-looking perspectives that the work of digital art history can open up. As variously as it has been defined, digital art history, at core, centers the use of digital tools and approaches to transform the study of objects and the built environment.5 It recognizes the potential that digital tools hold for the analysis of large volumes of data and the visualization of patterns, connections, and gaps among these data—thus the “distant-looking perspective” invoked here—for which analogue methods may be less well suited.

I also imagined that teaching remotely would allow me to open up my course and curriculum to accommodate multiple voices from both within and outside the Amherst community and in so doing undermine the art history classroom’s conventional emphasis upon the specialist expert as the lone generator of knowledge. In the event, we welcomed twelve visitors to the remote course, including the other contributors to this series, Nancy Um (then at Binghamton University, now at the Getty Research Institute) and Susan Elizabeth Gagliardi (Emory University). The former provided an indispensable tutorial on the use of the digital platform Tableau to analyze museum collections databases, and the latter led a rich discussion on her and her collaborators’ Mapping Senufo: Art, Evidence, and the Production of Knowledge digital project. Two of our interlocutors, art historians Pika Ghosh (Haverford College) and Dipti Khera (New York University/The Institute of Fine Arts), sat in on most of the class sessions as unofficial auditors. Each also led class sessions on recent research in their areas of specialization (analogue and digital remediation of Bengali painted narrative scrolls (patas), in the case of Ghosh; feeling and emotion (bhava) in the study of large-scale paintings from Udaipur, India, in the case of Khera). Miloslava Hruba, the study room manager at Amherst’s Mead Art Museum and a specialist of European prints, was also regularly present during these meetings. Indeed, Hruba—by virtue of her specialist knowledge of the Mead’s database and access to the physical collections—ended up playing a fundamental role in the execution of the course, a fortuitous outcome that I had not anticipated when I first envisioned it. Teaching a digital art history course remotely both required and fostered an extensive colearning network, although, to be clear, I alone was responsible for the evaluation of the students’ work.6

But in choosing to center the Mead Art Museum’s collections, the students and I had to reckon with the peculiar challenge of studying objects to which we did not have ready physical access. Of the nine students who registered for the course, only two were on campus that fall. Three other students—two from Hampshire College, and one from Smith College—were in the vicinity, but the COVID-19 protocols in place at Amherst College precluded their admittance to the campus and its buildings.7 Further compounding the problem was the fact that a number of the South Asian objects in the Mead’s collections had not yet been photographed; although they enjoyed a presence in the museum’s online database, their digital entries lacked any form of visual documentation.

I characterize this challenge as “peculiar” because close examination of objects has long been among the key methods exercised in art history courses, including my own. The formal analysis paper, a mainstay of art historical pedagogy, centers this approach by inviting students to examine works of art as autonomous syntheses that with careful observation can reveal critical information about the contexts in which they were meant to be circulated or consumed. Jennifer Roberts’s championing of “deceleration, patience, and immersive attention” has reinvigorated the discipline’s commitment to “slow looking,” as David M. Lubin recently dubbed it, and object-focused teaching.8 In all her courses, Roberts requires each student to spend three hours looking at a single object in anticipation of writing a research paper about it. The process underscores the prolonged spans of time that our visual apparatuses require to perceive works most fully, while it foregrounds the object as the primary unit of analysis. The object in these instances figures as both the beginning and end of art historical inquiry.

In our case, however, the object, much like our class, had been rendered fully and irreparably remote. While we devoted a good part of the semester to looking closely at digital photographs of South Asian objects in the Mead, we spent much of our time training our eyes on electronic spreadsheets instead.9 Like many museums, the Mead utilizes a collections management system to compile and organize vast quantities of metadata, from objects’ dates and places of production to their dimensions, mediums, makers, patrons, former owners, and more.10 As robust as such databases are, their architecture tends to represent metadata and metadata fields as static entities. By exporting this information to a structured data format, such as a comma-separated values (CSV) file or a spreadsheet, one can, in contrast, easily sort and filter the metadata. The tabular configuration of structured data is by no means more “natural,” nor are its contents “raw”; its layout is, like the database entry, “a form of information visualization,” meaning that its appearance is the product of multiple human interventions and remediations.11 But unlike the database entry, the structured data format of the spreadsheet permits one to rearrange the metadata and metadata fields, and thereby reveal, and potentially upend, the information hierarchies, systems of categorization, and practices of naming that databases naturalize. It also allows us to examine objects in the aggregate—in this case, through the large quantities of metadata associated with them—in a way that the museum gallery and storeroom do not. These operations facilitate a different kind of “slow looking,” one that acknowledges the many kinds of technological, cultural, and historical traces that semantically (and otherwise) inhere in the objects that museums accession.

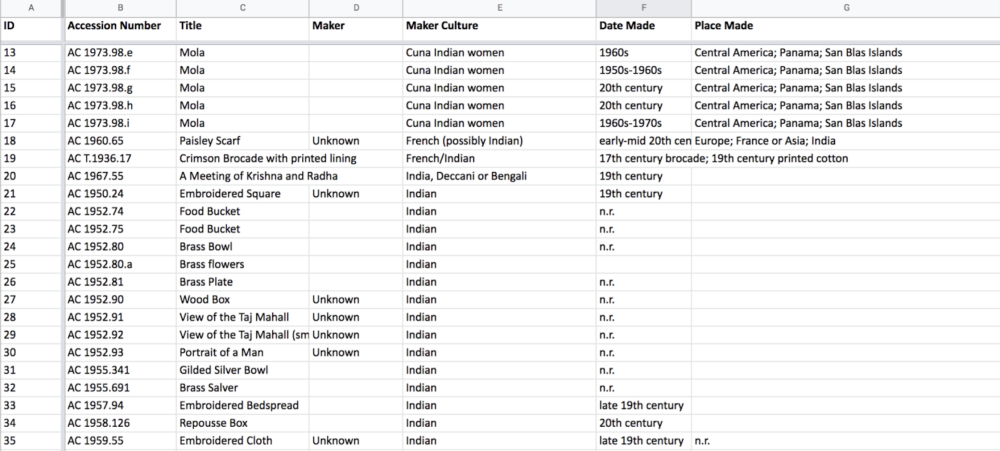

One of the first exercises that I assigned my students, for example, asked them to identify and filter the Indian, Pakistani, Nepali, and Tibetan objects in a spreadsheet containing all the Mead’s collection metadata, which had been exported from the museum’s database. Running a keyword search for “India,” for one, returned hits for objects from India, but also for Native American materials and works produced with India ink (above). That a query for this one term should produce such incongruous results was not a mere accident: the makers of early modern European inventories used this nomenclature to denote foreignness more broadly, whether describing objects from India and other parts of South Asia, or from East Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and the Americas.12 India ink, originally associated with Japanese and Chinese production—and hence also known as “China ink”—was apparently so named by seventeenth-century English traders who imported the black ink cakes to Europe via the subcontinent. The seemingly simple task of identifying what was and was not “Indian” in the dataset, in other words, brought to light the “historical underpinnings of systems of categorization” and their often deeply Eurocentric biases.13

The exercise also forced students to reckon with ambiguities in the museum dataset. One of the works that their searches pulled up had been characterized as hailing from “Tibet or Yunnan”; two others, both textiles, bore the comparable, but differently worded, designations “French/Indian” and “French (possibly Indian).” The use of this terminology raised the question of what it means to be culturally hybrid or indeterminate, and whether objects of uncertain origin even belonged in our new, filtered dataset.14 While the confusion between Tibet and the geographically contiguous province of Yunnan made immediate sense, just how an Indian textile could be mistaken for French required a deeper awareness of larger historical processes, including the European monopolization of the textile trade in India during the later eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the eventual adaptation of printing techniques once unique to India by French artisans.15 We were exercising, in this sense, what Roopika Risam has called “postcolonial digital pedagogy,” an approach that “empowers students to not only understand but also intervene in the gaps and silences that persist in the digital cultural record.”16 Beyond wrestling with complicated histories of colonial exploitation and extraction, students had also to contend with how they, like all cataloguers, intermediate—indeed, produce—museum knowledge, thereby shaping the histories and identities of the objects that we view in these institutions.

Once the students had identified the Indian, Pakistani, Nepali, and Tibetan objects in the Mead collections and filtered them into a structured data format, in this case an electronic spreadsheet, they then had to sort, or organize, the metadata, and reconcile any misspellings, duplications, inconsistencies, lacunas, and incorrect formatting. Among other insights, these acts of data cleaning shed light on how museum database structure information according to culturally inflected principles. This point became plainly evident because the structured data file into which the Mead’s metadata had been exported reproduced the database’s information hierarchy. Thus, the spreadsheet’s first three columns, following the database’s own logic, were reserved for the objects’ accession numbers, titles, and maker’s (or makers’) names, and in that order. Through the process of examining the Mead’s collection metadata in a spreadsheet, students were able to grasp how the database’s information architecture privileged those places and periods of time in which makers’ names had been preserved. The maker column included numerous names, for example, associated with the production of objects of European origin. The majority of the makers of the Indian, Pakistani, Nepali, and Tibetan works, on the other hand, had been registered as “unknown,” a term that masks the fact that not all cultures deem it necessary, or even desirable, to preserve this information. In many cases, vital information about the producers of objects from Asia, Africa, and the Americas had been lost, due to the manner in which they were collected during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Neither the database entry nor the museum label, both of which prioritize individual makers’ identities, typically elucidates these fundamental biases about what matters in art production.

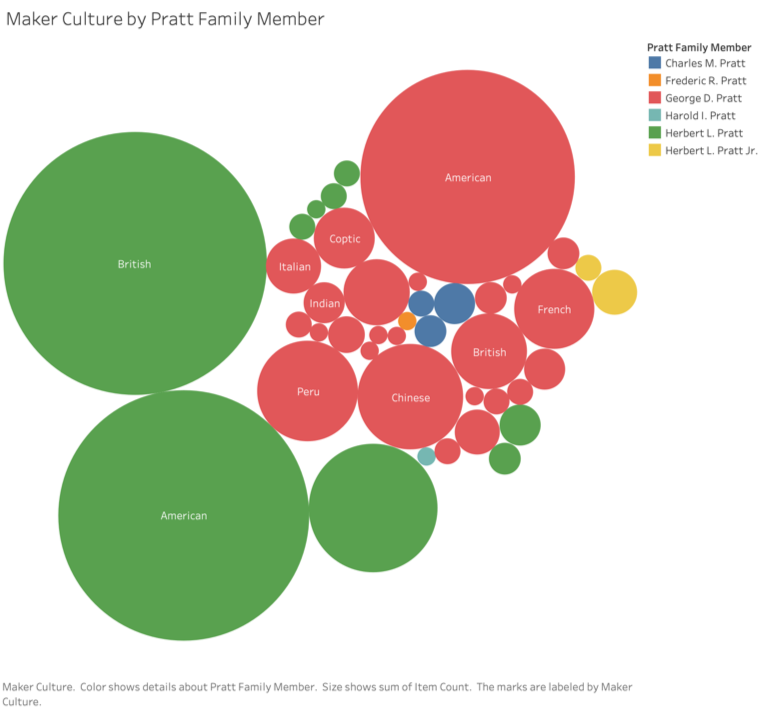

Contrary to the standard database, the structured data format of the spreadsheet can be easily edited—columns, for example, can be moved, removed, renamed, and added—to produce new hierarchies of documentation. In our case, the students had the capacity to transpose the “maker” with the “materials” column, and thereby foreground these aspects of the objects’ histories over the (unknown) identities of their producers. Using the spreadsheet as one of their primary analytical lenses, the students could also sort the dataset according to physical dimensions (from largest to smallest, or the reverse) and credit line. Sorting the Mead’s full dataset by donors, for example, yielded unexpected insights about the different kinds of materials—from Japanese ceramics and British engravings to Russian icons—that the former owners of Indian, Pakistani, Nepali, and Tibetan objects in the collection had also once counted among their possessions. The graphs that students created with their datasets helped to visualize these relationships (above), but it was the very fungibility of the spreadsheet that enabled the initial detection of these otherwise obscured points of connection.17

Hannah Turner, in her recent Cataloging Culture: Legacies of Colonialism in Museum Documentation, argues that “despite decades of postcolonial research and revision, object names and classification terms seem to stick to existing records.”18 In the context of our course, the distant-looking perspective that filtering, sorting, and cleaning these metadata in a spreadsheet opened up allowed the students to perceive the “temporal ‘build-up’ or ‘stickiness’ of terms, categories, and practices, which is linked to earlier epistemological modes.”19 One student’s examination of the language used in the “notes” column in our dataset revealed how these processes had come to bear upon several textiles and textile fragments in the collection. These included a twentieth-century shawl, probably of French origin, that had been described therein as “Oriental-like.” Although “Oriental” is still used in some museum quarters, especially to describe textiles, the term has been deemed by many to be too fraught due to its overly broad scope, Eurocentric basis (the Latin oriens, from which oriental derives, means “east”), and association with European exoticization and domination of Asia. Indeed, the Getty’s Art & Architecture Thesaurus, a standard controlled vocabulary that many museums employ today, identifies “Asian” as the preferred descriptor.20 Label text penned at the Mead in the last twenty years registers a clear awareness of the legacies of Orientalism, yet its discursive residues, as this student discovered in the process of looking distantly at the objects of our study, still inhere in the museum’s metadata.21 Our interventions cannot end with digitization of metadata if that means that “we are effectively digitizing our field’s past into our technological present.”22

The final assignment for the course invited each student to write a blog post–like essay, drawing upon the tools and resources introduced earlier in the course to analyze one or more South Asian objects in the Mead’s collection dataset, and to discuss their methods and present their findings in a symposium conducted via Zoom, to which the Mead Art Museum staff and the various visitors to the course were invited.23 This exercise was meant to provide students the opportunity to build upon other activities and tasks that they had completed over the course of the semester. These included open-ended discussions and short written responses, as well as more specific, guided lessons, like those described above, in addition to a mapping exercise and a museum podcast review.

The final assignment was, furthermore, intended to emphasize the important public-facing contributions of the students’ (and all museum workers’) labor.24 In expanding their audience to the larger community beyond the classroom, I hoped to underscore the broader ramifications of their projects and of the skills and concepts that they had used to execute them. I indeed discerned a subtle shift in the tone and voice that the students adopted in their oral and written presentations of the projects, as they had come to understand that their work—in spite (or precisely because) of its digital nature—had very timely and concrete applications.

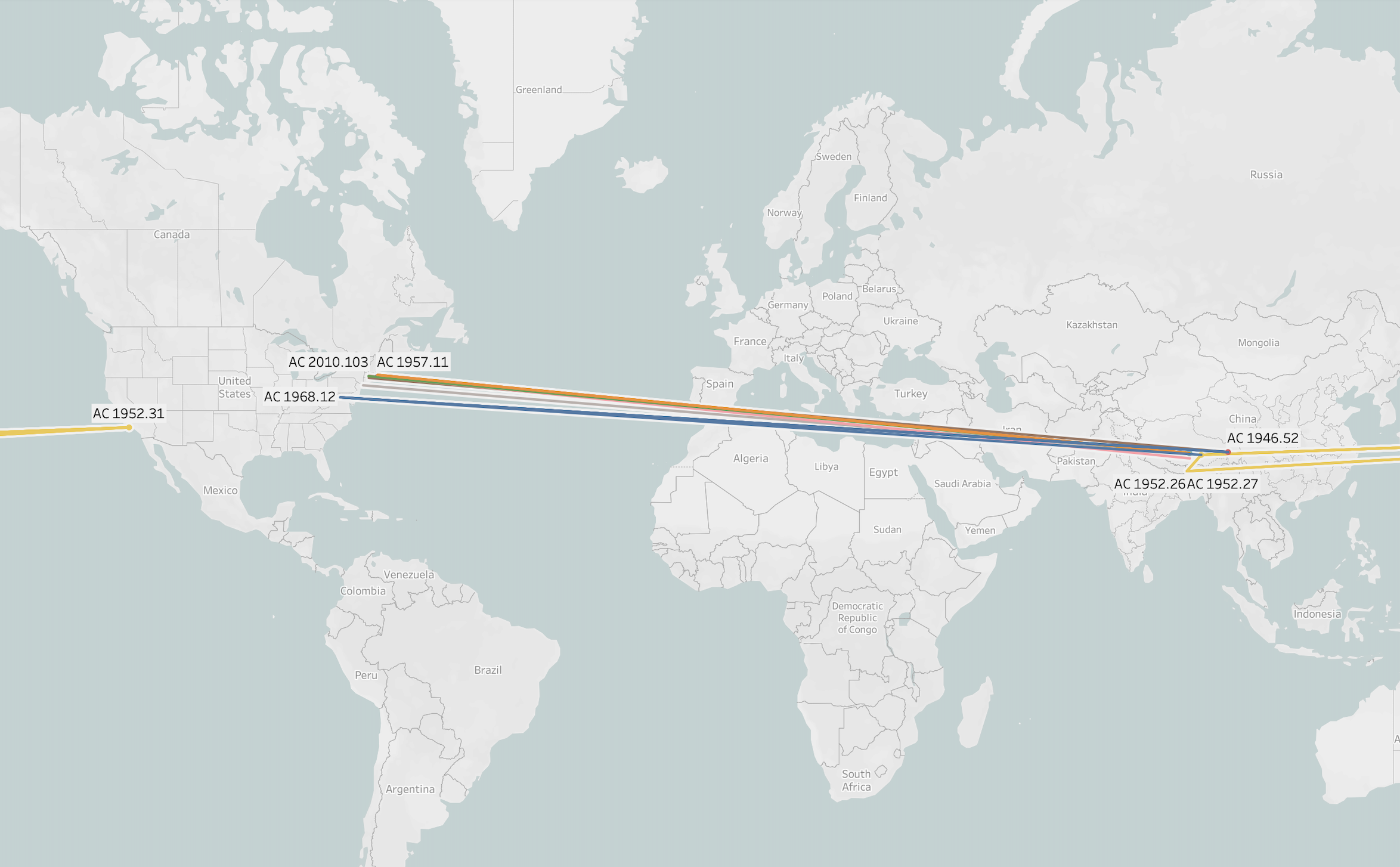

One student, for example, used the spreadsheet to analyze metadata drawn from the digital database and analog records—including handwritten letters; old, printed labels; conservation reports; and donor’s documents—that were associated with Tibetan objects in the Mead’s collections. With this trove of information—much of which had remained otherwise “hidden” due to its absence from the digital database—the student created map visualizations that conjecturally tracked where the various materials (plant-, mineral-, and animal-based pigments and binders, for example) used to create the Mead’s eighteen thangkas (Tibetan Buddhist paintings on cloth) had been sourced and by which routes overland they had traveled.25 They then created a second map that traced the movement of seven Tibetan objects in the dataset from various monasteries in Tibet to new owners, namely private collectors and gallerists, in the United States (above). These exercises provided the student the opportunity to reflect critically upon the dissonances between political borders as they exist today and as they existed prior to the mid-twentieth century. They also offered the student insights about the longer lives of thangkas, in particular the circuitous routes that brought them into being, made them fit for use as objects of devotion in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, and then transformed them into objects of art.26

The questions that this student pursued had found their impetus in the structured data format of the electronic spreadsheet, but their investigation drew equally as much from the thangkas and the physical archival materials related to them. This point underscores how digital art history is, or could be, a deeply iterative activity.27 Far from being rooted solely in a purely abstract, immaterial domain, digital art history demands that objects and their physical metadata be taken seriously. Tellingly, among the ways that the student imagined that their project might be expanded was to use digital tools to virtually—and then physically—reconstruct the textures and smellscapes of some of the thangkas in the collections. The digital, in other words, had brought issues related to materials, materiality, and accessibility to the fore.28

Close and slow looking at objects surely will, and should, remain a cornerstone of art historical pedagogy, but, as these case studies show, the more distant kind of looking that digital art history tools and approaches invite can also bring to light how, to quote Turner once again, museum objects are “discursively produced.”29 The Williams College Museum of Art’s exhibition Accession Number (2017) and metaLAB programs at Harvard’s Light Box venue (inaugurated 2016) have recently demonstrated that gallery spaces offer generative, provocative settings for examinations of and interventions into museum collections and their metadata. These kinds of inquiries are increasingly possible because the Williams College Museum of Art and a host of other institutions have made their collection datasets publicly available to download online.30 Likewise, the classroom—whether in-person or online—can and should be deployed towards similar ends.

Failure to teach our students that “we are active participants in the maintenance of our field’s information infrastructure,” as Emily Pugh has put it, is a grave danger indeed.31 The recent popularization of artificial intelligence tools like DALL-E, a machine learning model created by the for-profit corporation OpenAI that uses natural language descriptions (such as museum object labels and other discursive metadata that can be scraped online) to generate images, is a case in point. DALL-E may not possess inherent bias, but it will reproduce the biases that inhere in the metadata that it employs. A recently published study of displays of trustworthiness based on facial cues in Western European painted portraits produced between 1500 and 2000 likewise failed to acknowledge the limitations of its sources and methods.32 Conducted by a group of cognitive scientists, the study drew its evidence solely from digital photographs of portraits in the National Portrait Gallery, London, yet the team did not account for the fact that these data are remediated representations of the paintings that were the actual focus of the investigation.33 Nor did it address the drawbacks of using a single museum’s collection to formulate sweeping hypotheses about five-hundred years’ worth of Western European portraiture, or the essential point, understood by art historians, that portraiture is “is the product of intersecting demands and desires” and not, as the study’s authors presumed, a reflection of reality.34

To train students of art history to “intervene in the gaps and silences that persist in the digital cultural record,” according to Risam, necessitates recourse to a more multidisciplinary approach to teaching.35 But we need not sacrifice close attention to the physical aspects of the objects that we study. As my students discovered, attention to the digital can yield new and surprising insights about objects and their material properties and histories. The contexts and challenges of online teaching, in a similar vein, prompted my own reexamination of art historical methods and pedagogies.36 Like the specter of an endless pandemic, digital technologies and their algorithms are here to stay. Let us prepare ourselves and our students accordingly.

Acknowledgements

Many individuals had a hand in the planning and execution of the Amherst College fall 2020 Digital Art History course that is the focus of this essay. Among them, I wish to acknowledge the nine students who participated in the course as well as Miloslava Hruba, Stephen Fisher, Tim Gilfillan, Megan Lyster, Andy Anderson, Emily Potter-Ndiaye, Lisa Crossman, Amanda Henrichs, Nicola Courtright, Deborah Diemente, David E. Lazaro, Elizabeth Gallerani, Susan Elizabeth Gagliardi, Nancy Um, Matthew Lincoln, Siddhartha Shah, Dipti Khera, Pika Ghosh, Priyanjali Sinha, Sarah Laursen, and Alexander Brey. For generously reading and commenting on earlier drafts of this essay, I thank the two anonymous peer reviewers, Pika Ghosh, Sonja Drimmer, Miloslava Hruba, and especially my two collaborators in this series, Nancy Um and Susan Elizabeth Gagliardi. Finally, I wish to thank Nicole Archer, editor extraordinaire, for supporting publication of this essay and the larger series of which it is part, not least in the thick of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yael Rice is associate professor of art history and Asian languages and civilizations at Amherst College. She specializes in the art and architecture of South Asia, Central Asia, and Iran, with a particular focus on manuscripts and other portable objects of the fifteenth through eighteenth centuries. She is the author of The Brush of Insight: Artists and Agency at the Mughal Court (University of Washington Press, forthcoming in 2023).

- Although I conceived of this course as an introduction to digital art history, its numbering in the course catalog reflected its status as an intermediate-level, cross-listed course in Amherst College’s Department of Art and the History of Art and in the related Program in Architectural Studies. (The course description may be viewed here.) Like many of the courses I teach at Amherst, the course carried no prerequisites, and while it could be counted towards completion of the History of Art or Architectural Studies major, it was not a requirement for either. Membership in the course included History of Art majors as well as other humanities, social sciences, and STEM majors. Several of the nine students enrolled in the course were double majors; some of these combinations included History of Art and Computer Science; History of Art and Sociology; and Economics and Architectural Studies. ↩

- The course took as its purview South Asian objects more broadly, but focused specifically on those places (today’s India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Tibet) represented by works in the Mead Art Museum’s collections. ↩

- A revised version of the course syllabus from October 14, 2020 may be viewed here. Note that this version of the syllabus retains deleted information (here indicated by strikethrough text) for assignments, exercises, and class visits that had to be canceled or rescheduled. ↩

- On interdisciplinarity in the method and teaching of art history, see, for example, Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis, “Transforming the Site and Object Reports for a Digital Age: Mentoring Students to Use Digital Technologies in Archaeology and Art History,” The Journal of Interactive Technology & Pedagogy 7 (May 10, 2015); and Marie Gasper-Hulvat, “Active Learning in Art History: A Review of Formal Literature,” Art History Pedagogy & Practice 2, no. 1 (2017). Art History Pedagogy & Practice, an open access peer-reviewed e-journal, is, on the whole, an excellent resource for this topic. ↩

- Just what digital art history is, should, and could be has been the focus of a number of salient essays published in recent years. See, among them, Johanna Drucker, “Is There a “Digital” Art History?,” Visual Resources 29, nos.1–2 (2013): 5–13; Pamela Fletcher, “Reflections on Digital Art History,” caa.reviews, June 18, 2015; Murtha Baca, Anne Helmreich, and Melissa Gill, “Digital Art History,” Visual Resources 35, nos. 1–2 (2019): 1–5; Nuria Rodríguez-Ortega, “Digital Art History: The Questions that Need to Be Asked,” Visual Resources 35, nos. 1–2 (2019): 6–20; Paul B. Jaskot, “Digital Art History as the Social History of Art: Towards the Disciplinary Relevance of Digital Methods,” Visual Resources 35, no. 1–2 (2019): 21–33; and Emily Pugh, “Art History Now: Technology, Information, and Practice,” International Journal of Digital Art History 4 (2019): 3.47–3.59. ↩

- Other visitors to our course included Andy Anderson (Academic Technology Specialist), Emily Potter-Ndiaye (Head of Education and Curator of Academic Programs, Mead Art Museum), and Lisa Crossman (Curator of American Art and Art of the Americas, Mead Art Museum), all of Amherst College; and Matthew Lincoln (then Collections Information Architect, Carnegie Mellon University, now Senior Software Engineer for Text & Data Mining, JSTOR Labs), Siddhartha Shah (the then Director of Education and Civic Engagement and Curator of South Asian Art, Peabody Essex Museum, now Director of the Mead Art Museum, Amherst College), Murad Khan Mumtaz (Assistant Professor of Art, Williams College), and Priyanjali Sinha (then a graduate student in Landscape Architecture, University of Pennsylvania). In every case, our interlocutors engaged actively with the class by leading discussions and/or technical tutorials. The combination of local and nonlocal specialists, some possessing digital humanities expertise and some not, was intended to provide students with a diverse introduction to a wide range of current art historical (especially South Asia-centered) and curatorial methodologies. ↩

- Amherst College is a member of the Five College Consortium, which also includes Hampshire College, Smith College, Mount Holyoke College, and the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. A distinct advantage of this arrangement is that students at these institutions are able to enroll in the broad array of courses offered across the Consortium. ↩

- Jennifer Roberts, “The Power of Patience,” Harvard Magazine (Nov.–Dec., 2013); and David M. Lubin, “Slow Looking,” History of Art at Oxford University blog, July 26, 2017. ↩

- Digital photographs, like digital spreadsheets, significantly remediate the objects that they represent. On this important point and the need to reflect on the technologies and digital frames that art historians use and teach with, see Teaching Art History with New Technologies: Reflections and Case Studies, eds. Kelly Donahue-Wallace, Laetitia La Follette, and Andrea Pappas (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008); Elli Doulkaridou, “Reframing Art History,” International Journal for Digital Art History 1 (2005): 67–83; and Alison Langmead, “Art and Architectural History and the Performative, Mindful Practice of the Digital Humanities,” The Journal of Interactive Technology & Pedagogy 12 (February 12, 2018). ↩

- The Mead Art Museum currently uses MIMSY XG (Version 1.6.7) as its primary collections management database. ↩

- Elijah Meeks, “Spreadsheets are Information Visualization,” Stanford Digital Humanities blog, April 28, 2014. ↩

- Jessica Keating and Lia Markey, “‘Indian’ Objects in Medici and Austrian-Habsburg Inventories,” Journal of the History of Collections 23, no. 2 (2011): 283–300. ↩

- Hannah Turner, Cataloging Culture: Legacies of Colonialism in Museum Documentation (Vancouver and Toronto: University of British Columbia Press, 2020), 14. Along similar lines, see also Geoffrey C. Bowker and Susan Leigh Starr, Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999), and, in an art historical vein, Pugh, “Art History Now,” and Susan Elizabeth Gagliardi, “Mapping Senufo: Mapping as a Method to Transcend Colonial Assumptions,” in The Routledge Companion to Digital Humanities and Art History, ed. Kathryn Brown (New York: Routledge, 2020), 135–54. ↩

- On hybrid objects and the utility of the term “hybridity” in the transnational study of art history, see, among others, Carolyn Dean and Dana Leibsohn, “Hybridity and Its Discontents: Considering Visual Culture in Colonial Spanish America,” Colonial Latin American Review 12, no. 1 (2003): 5–35; Monica Juneja, “Global Art History and the ‘Burden of Representation,’” in Global Studies: Mapping Contemporary Art and Culture, eds. Hans Belting, Jacob Birken, Andrea Buddensieg, and Peter Weibel (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2011), 274–97; Stephanie Porras, “Locating Hispano-Philippine Ivories,” Colonial Latin American Review 29, no. 2 (2020): 256–91; and Holly Shaffer, “Eclecticism and Empire, in Translation,” Modern Philology 119, no. 1 (2021): 147–65. ↩

- On these historical phenomena, see Giorgio Riello, “The Globalisation of Cotton Textiles: Indian Cottons, Europe and the Atlantic World, 1600-1850,” in The Spinning World: A Global History of Cotton Textiles, 1200–1850, eds. Giorgio Riello and Prasannan Parthasarathi (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 261–87; and idem, “How Chintz Changed the World,” in Cloth that Changed the World: The Art and Fashion of Indian Chintz, ed. Sarah Fee (Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum, 2019), 192–201. ↩

- Roopika Risam, New Digital Worlds: Postcolonial Digital Humanities in Theory, Praxis, and Pedagogy (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2019), 89. ↩

- The history of collecting South Asian art outside of South Asia was the focus of the recently published Arts of South Asia: Cultures of Collecting, eds. Allysa B. Peyton and Katherine Anne Paul (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2019). On this subject, as well as the consequences of the repatriation of Hindu devotional objects to India, see also Richard Davis, The Lives of Indian Images (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997). ↩

- Turner, Cataloging Culture, 16. Although Turner’s study addresses this phenomenon in the context of natural history museums in the United States, in particular, the insight also bears upon museums of fine arts, too. ↩

- Turner, Cataloging Culture, 186. ↩

- To illustrate this point, a search for “Oriental” in the Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus Online returns the entry for “Asian,” accessed January 30, 2021. ↩

- See, for example, the label text for Dotty Attie’s Sometimes a Traveler/There Lived in Egypt (AC 2002.366.1) and Lalla Essaydi’s Les femmes du Maroc #14 (Women of Marocco) (AC 2007.13). ↩

- Pugh, “Art History Now,” 3.54. ↩

- The description of the final project for the course may be viewed here. ↩

- The often-underappreciated value of museum workers’ labor is a subject that has recently emerged more fully in the public sphere, thanks to strikes mounted by unionized employees at a number of major museums across the United States, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in North Adams, Massachusetts, among others. This immensely important issue is unfortunately beyond the scope of the present essay and deserving of its own separate treatment. ↩

- Along these lines, see Mapping Color in History, a digital project that provides “a searchable database of pigment analysis used in Asian painting,” accessed November 22, 2022. Jinah Kim, the George P. Bickford Professor of Indian and South Asian Art at Harvard University, spearheaded this multidisciplinary digital project. ↩

- For more information about the Mead’s collection of Tibetan thangkas, see Marilyn M. Rhie, Robert A.F. Thurman, Maria R. Heim, Paola Zamperini, Camille Myers Breeze, and Elizabeth E. Barker, Picturing Enlightenment: Tibetan Tangkas in the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College (Amherst: Mead Art Museum, 2013). And on the status of thangkas as both devotional objects and commodities, see Ming Xue, “Strategic Commodification: The Object Biography of Tibetan Thangka Paintings in Contemporary China,” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 11, no. 3 (2021): 1153–67. ↩

- On the importance of integrating quantitative and qualitative methods in digital humanities scholarship, see Claire Lemercier and Claire Zalc, “History by Numbers,” Aeon, September 2, 2022. ↩

- Among the digital projects and readings that inspired these investigations were Bagan—Embracing the Future to Preserve the Past, accessed November 21, 2022; Keith Wilson’s Cosmic Buddha project, described in “The Cosmic Buddha,” accessed November 21, 2022; W. Brent Seales, “Visualizing PHerc.118,” Thinking 3D, January 26, 2018; and Néstor F. Marqués, “Vilamuseu: 3D scanning and 3D printing for Accessibility,” sketchfab.com, January 23, 2018. An exemplary museum exhibition in this vein was Revealing Krishna: Journey to Cambodia’s Sacred Mountain (accessed November 22, 2022), which used holographic imaging to reimagine a 1500-year-old Cambodian sculpture of Krishna, now in the collections of the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA), in its original context. The exhibition was curated by Sonya Rhie Mace, the George P. Bickford Curator of Indian and Southeast Asian Art at the CMA, and mounted at the CMA and the National Museum of Art, Washington, D.C., during 2021–22. ↩

- Turner, Cataloging Culture, 4. On the consequences of the digital remediation of museum objects, see also Haidy Geismar, Museum Object Lessons for the Digital Age (London: University College of London Press, 2018). ↩

- GitHub, a web-based repository, hosts a number of museum collections datasets, including those of the Williams College Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Museum of Modern Art, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian. Contemporary artists like Refik Anadol are also making use of these freely accessible digital collections. For his Unsupervised, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York City until March 2023, Anadol “trained a sophisticated machine-learning model to interpret the publicly available data of MoMA’s collection,” accessed November 21, 2022. I am grateful to Susan Elizabeth Gagliardi for bringing this exhibition to my attention. ↩

- Pugh, “Art History Now,” 3.56. On the perils of art history’s technological belatedness, see also Drucker, “Is There a “Digital” Art History?”; and Nancy Um, “Teaching the Practices of Art History in the Age of Abundance,” Art Journal Online, December 8, 2022. ↩

- Lou Safra, Coralie Chevallier, Julie Grèzes, and Nicolas Baumard, “Tracking Historical Changes in Perceived Trustworthiness in Western Europe using Machine Learning Analyses of Facial Cues in Paintings,” Nature Communications 11, no. 4728 (September 2020). ↩

- For an art historical critique of this study and others related to it, see Sonja Drimmer and Yael Rice, “How Scientists Use and Abuse Portraiture,” Hyperallergic, December 11, 2020. ↩

- Drimmer and Rice, “How Scientists Use and Abuse Portraiture.” ↩

- Risam, New Digital Worlds, 89. ↩

- In the draft description (accessible here) for The Museum in the Digital Age, an intermediate-level course that I plan to teach at Amherst College in fall 2023, I make explicit the focus on museums, collecting, and categorizing that—unbeknownst to me when I initially designed the curriculum—became the centerpiece of my fall 2020 Digital Art History course. Among my goals in teaching The Museum in the Digital Age is to anchor the introduction to digital art history to current museum practices, museology, and cultural heritage studies, and to foreground the local institutional and community contexts in and to which students will learn and contribute. ↩