The landscape positions us at eye-level with a gray sky over a horizon of rolling mountains. We are looking both out and below from an omniscient nonplace. The eye cannot help but dance between these topographic qualities of the mountains and the words on the cover of Beth Macy’s Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America (2018).1 From the title, the eye passes over the far-off mountains, punctuated in the center by an industrial chimney. These signs of industry cause the mist coming out of the valley to appear more menacing than would a naturally occurring effect of mountain geography. Closer to us, directly following the author’s byline, powerlines stretch out to the right like a signature flourish. The bold, harsh title and subtitle over industrially altered mountains throws the smattering of heterogeneous houses and the lone car at the bottom of the image into relief as pitifully small.

Captions, as Roland Barthes reminds us, anchor a photograph’s meaning.2 Seeing a human-altered landscape completely empty of bodies, framed by the word “SICK”—not to mention the reference to America’s “troubled soul” in its blurb, written by none other than Tom Hanks—gives a sense of ruin that will be familiar to readers who have been confronted with news about environmental ruin for decades. This connection suggests that extractive, unregulated capitalism and industry has stretched to the country’s soul, and that all of this is related to an addicted America.

Dopesick’s cover is part of what I am calling here the visual culture of the opioid epidemic in America. This project is rooted in the observation that a specific type of landscape photograph, a rural setting devoid of human figures, has been repeatedly used on the cover of nonfiction publications about the opioid epidemic since 2015. In New York City, where I live, I saw versions of this image paired with threatening titles about opioids staring out at me from bookstore windows and propped up on tables in airports and train stations. Previous art history scholarship on the visual culture of journalism has fittingly focused largely on magazines, which feature images on nearly every page.3 Magazines tend to be geared toward a wide audience and are ephemeral, “typically perused for a week or a month and tossed out when the next issue arrives,” in the words of Emily Hage.4 Books are designed to be more permanent and can potentially become a feature of household decor, their spines seen on home bookshelves for years following their purchase. This is not to say that buying a book is an aesthetic decision, but that book design does the rhetorical work of visual culture by inflecting the book’s narrative and metanarrative. My aim here is to evaluate how book design has responded to and perpetuated our understanding of the opioid crisis as a problem of white, rural America in decline.

The photographs on these covers borrow stylistically from the “New Topographics” photographers Robert Adams (b. 1937) and Steven Shore (b. 1947), and their predecessors, namely Walker Evans (1903–1975), in the service of telling a particular story about the rising rates of opioid overdose in many rural parts of the country by using the exhausted American landscape as a metaphor. This is a marketing formula that began with Sam Quinones’s Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic (Bloomsbury, 2015) and J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy (Harper, 2016), the latter focusing heavily on the author’s opioid-addicted mother. Both of these books were used as market comps for future books on the subject, so that a formula calcified for how to sell this subject to readers.5 We see views of landscapes and small towns in Chris McGreal’s American Overdose: The Opioid Tragedy in Three Acts (Public Affairs, 2018), John McMillian’s American Epidemic: Reporting from the Front Lines of the Opioid Crisis (New Press, 2019), Eric Eyre’s Death in Mud Lick: A Coal Country Fight against the Drug Companies that Delivered the Opioid Epidemic (Scribner, 2021), and at least five other nonfiction books published since 2016.6 The images are mostly by photojournalists in the authors’ networks or sourced from image banks by book designers. My interest is not so much in the design and marketing processes of publishers as in why these images are an intelligible and enduring metaphor for the epidemic.

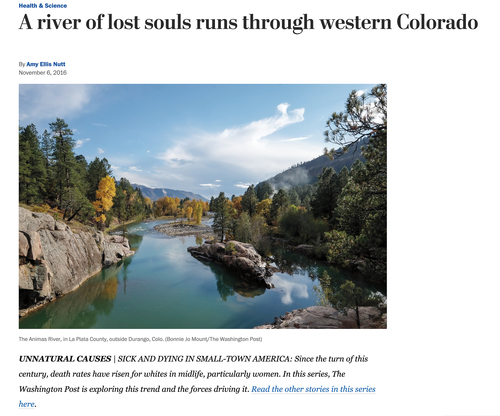

Beginning in 2016, media focus on the rising rates of opioid addiction and overdose deaths grew alongside interest in the popularity of Donald Trump as a presidential candidate.7 Headlines such as “Drug Deaths Reach White America,”8 “Why Are White Death Rates Rising?,”9 “Why Death Rates for White Women in Rural America are Spiking,”10 and “Opioids and Anti-anxiety Medication are Killing White American Women”11 inaugurated the genre of opioid epidemic coverage that these books are part of. Landscape figured prominently in these stories too, such as the Washington Post articles, “A River of Lost Souls Runs through Western Colorado” and “An Addiction Crisis Along ‘The Backbone of America.’”

Economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton coined the term “deaths of despair” in the 2015 paper “Suicide, Age, and Wellbeing: An Empirical Investigation,” but the term did not enter the public lexicon until the following year as a result of investigations into Trump’s popularity.12 Case and Deaton, and the vast corpus of investigative pieces that followed, reported that white people in America were abusing opioids because they were not only suffering from chronic pain due to decades of manual labor in coal mines and factories, but also because of high rates of depression, loneliness, and hopelessness caused by unemployment and poverty, especially in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008. This was followed by the public revelation of the role drug companies like Purdue Pharma have played in pushing OxyContin and other addictive opioids onto vulnerable communities for profit, giving the story resonances far beyond Trumpism, encompassing art museum patronage and outsized pharmaceutical lobbying power.13

“Our target reader,” Lauren Harms, the designer of Dopesick’s cover, tells me, “is very up to date with current events, reads a lot of news, and follows journalism.”14 Patti Ratchford, the designer of Dreamland’s cover, put this target audience more succinctly, as “New York Times readers.”15 Ratchford described choosing the image for the cover as wanting to specifically emphasize that addiction to opioids prescribed by doctors “could happen to anyone, your father, your husband, your sister.”16 Dreamland’s target reader is not actually “anyone,” but those who, we can surmise, are likely college-educated and urban or coastal.17

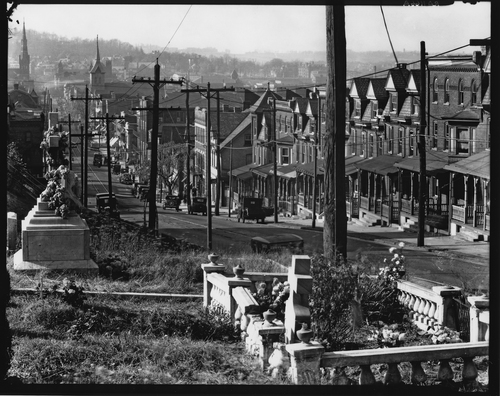

The image for Dreamland’s cover came from Ratchford searching Wikimedia for images of small towns, an evergreen signifier for “anyone,” and landing on the public domain image of Market Street in Portsmouth, Ohio, where the book’s opening salvo takes place. The distressed graphic evoking a torn postcard was added to signal tragedy, a rip in the titular dream. In Quinones’s book, the Mexican cartels who became wealthy by selling heroin to small-town white Americans are presented as a perversion of the American dream, which, the cover tells us, has been torn apart. In later versions, such as Harry Wiland’s facetiously titled Do No Harm: The Opioid Epidemic (2020), the town alone seems to stand for the broken dream.18

“A River of Lost Souls Runs through Western Colorado,” Washington Post, November 6, 2016 (screenshot by the author; published under fair use)

“An Addiction Crisis along ‘the Backbone of America’,” Washington Post, December 30, 2016 (screenshot by the author; image published under fair use)

Pete Garceau, jacket design for Harry Wiland, Do No Harm: The Opioid Epidemic, 2018 (image provided by Turner Publishing; published under fair use)

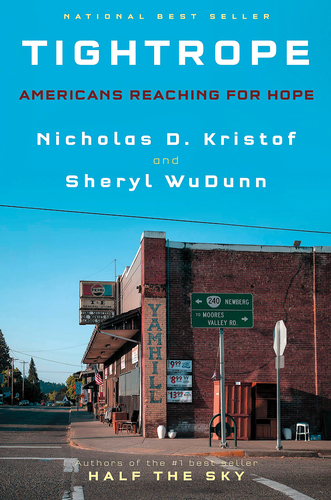

Cassandra J. Pappas, jacket design for Nicolas D. Kristoff and Sheryl WuDunn, Tightrope: Americans Reaching for Hope, 2020 (image provided by Knopf Doubleday; published under fair use)

The target reader of these books may sense that the story here is not only about a medical establishment that is corrupt despite being founded on principles of nonmaleficence, but also about racialized class structures breaking down in a nation that claims to be classless and upwardly mobile, thus tying the story to broader national anxieties. As Maia Dolphin-Krute argues in her book Opioids: Addiction, Narrative, Freedom, in such coverage, “the obligation is to explain both the destruction and a contemporary affect dominated by a loss of privilege, a dissolve of ‘fantasies of the good life,’ and a concurrent loss of optimism.”19 What Dolphin-Krute is referring to is the phenomenon studied by Case and Deaton of widespread poverty and hopelessness, but from the perspective of affect. I take my cue from Dolphin-Krute to ask why these affective dimensions here take the form of landscape.

The initial, obvious answer would be that the opioid crisis was initially reported on as a rural problem, aligning with the surge of interest in “flyover” states that helped to elect Donald Trump; and these are rural landscapes with gray skies that look as depressing as the topic at hand. Part of the job of the book cover is to “support the metaphoric weight of the entire book,” while diseases, as we know from Susan Sontag, often become metaphors for groups of people.20 However, both the opioid epidemic itself and its affective dimensions are not restricted only to rural America.21

These images visually connect the opioid crisis to the decline of America’s middle class by playing on idealized notions of small-town neighborhood. The threat of invisible contagion invading the social body is palpable in the cover of Do No Harm. The open parking spaces that take up the foreground eerily suggest that any life that was once here is now gone, while the vertical path of the road is intercepted by horizontal powerlines which send the eye up to the title. The static view from across the intersection recalls the Hollywood trope of the sole survivor of an apocalyptic event surveying their newly empty surroundings for the first time. Similar photographic and design techniques are deployed in Nicolas D. Kristoff and Sheryl WuDunn’s Tightrope: Americans Reaching for Hope (Knopf Doubleday, 2020). All of these images support books that tell similar stories of white Americans struggling with addiction, poverty, and a sense of hopelessness.

These images share a great deal in both style and function with the Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographs of the 1930s, which were frequently published in mainstream magazines and newspapers for the span of the project. Like the FSA photographs, the compositions of these book covers tell a particular story about the United States by doing the work of, in Cara A. Finnegan’s words, “circulating images that [make] some poverty stories more rhetorically available than others.”22 Compare, for example, the cover of Dreamland with Walker Evans’s Street in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Both feature a street lined with row homes stretching to a church spire, seen from the perspective of somebody standing at the intersection. The eye follows the street, but while for Evans it lands on the homes framed by telephone poles, on the cover of Dreamland it is led all the way to the spire pointing to the distressed graphic. The grave that takes up the foreground of Evans’s image asks us to consider the grief that the residents of these homes may face. The eye then has to travel across the street in order to reach the homes, establishing a dichotomy between life and death, our gaze landing on the side of life; as we follow the street, we leave the graves behind and move on. The image on the cover of Dreamland, with the empty road occupying the foreground, is hauntingly still and lifeless. The cover is designed so that the eye goes first to the title and then to the tear, so that we see the image as already torn, understanding the life of the town itself to be under threat.

This points to a crucial thematic difference between the two groups of images. Whereas the FSA’s Historical Section was ultimately a humanist project (not to mention propagandist), whose photographers emphasized the dignity of their subjects, coverage of the opioid epidemic has emphasized the exact opposite: the despair felt by underprivileged white Americans, which has driven them into the abject state of drug addiction. This lack of dignity is clear when people do appear in coverage of the epidemic. One image that went briefly viral in 2016 was posted on Facebook by the East Liverpool (Ohio) Police Department.23 A man and woman are passed out in the front seat of a car while a child in the back seat looks out at the camera. Consider this harrowing family scene, where the child is the only one alert, against any of the mothers in Dorothea Lange’s pictures who are animated by worry and heightened maternal instincts.

The police department photo is not a marketable image because it shows an aspect of the opioid crisis that runs counter to the media project of casting the issue as a systemic problem, one which implicates every American. The opioid crisis is one of addiction, but addiction is notoriously difficult to isolate from the attendant assumptions of norms and pathologies surrounding it. As art historian Julia Skelly writes, “The addicted individual … is materialized as abnormal through a range of gender, class and race-related discourses.”24 The disease itself—the compulsive drive to use drugs and the inability to stop—is a psychic disorder, one that apparently affects individuals, not groups of people. There are in fact several historical cases of addiction epidemics in communities, from the Opium Wars to the urban crack epidemic of the 1980s. Still, in the dominant “disease model” of addiction, addicted persons are treated (and punished) as individuals, not members of a group.

That the opioid crisis is cast as a systemic, environmental problem, and not one of criminality or personal choices, stems directly from the perceived whiteness of its victims. After all, a systemic view of the problem implies that the opportunity to make better choices is at least somewhat foreclosed. This view makes sense given that many people first became addicted on doctor’s orders. However, mainstream coverage of the opioid crisis has also used systemic factors to explain why people continue using opiates in an ongoing state of being addicted.

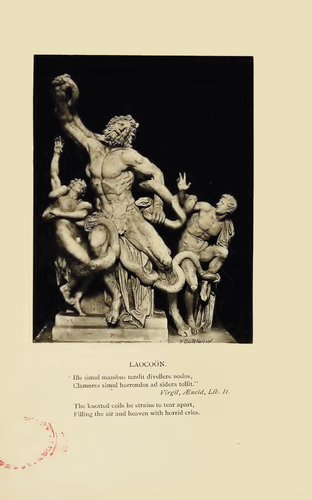

Historically in America, only white, male addicts have received compassion, care, and forgiveness from the public. In this way, today’s opioid epidemic mirrors the last wave of opioid addiction among white Americans in the 1880s, which saw the development of the disease model for addiction that informs how we now understand the problem. After the alkaloids for morphine and cocaine were isolated and marketed in the mid-nineteenth century, the drugs were readily prescribed to those who could afford medical care for a range of ailments. Many middle- and upper-class individuals became physically dependent on these substances. The medical framework which had been developed for treating alcoholism in the nineteenth century was forced to expand to accommodate new kinds of dependency. In 1881, New York physician H. H. Kane published Drugs that Enslave: The Opium, Morphine, Chloral and Hashish Habits, with a photographic reproduction of Laocoön and His Sons as a frontispiece and an epigraph from Virgil: “The knotted coils he strains to tear apart/Filling the air and heaven with horrid cries.” Another New York physician, George Wheelock Grover, published in 1894 his own treatise on “the Morphine, Opium, Cocaine, Chloral and Hashish Habits,” which described in florid prose the plight of “the 2,000,000 lives in these United States of America that are bound in the steel chains of the drug bondage . . . in the fearful grasp of the tyrant that controls them because of a mind that seeks relief, of a brain that cannot apply the brakes to thought.”25

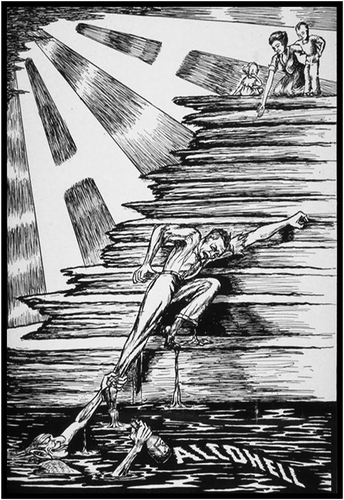

The enduring metaphors for addiction as enslavement and descent are repeated in an early promotional image for Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) following the program’s inception in 1935. Echoing Laocoön straining against his knotted coils, a man emerges from the river labeled “Alcohell” to climb up a stack of pages—representing AA’s emphasis on literature—toward a woman and children waiting at the top. In the river a grinning demon holding a bottle grips the man’s foot, but he places all his might in a heroic effort toward the summit.

H. H. Kane, Drugs That Enslave, 1881, frontispiece showing sculpture Laocoön and His Sons, Philadelphia: P. Blakiston (image provided by Open Knowledge Commons and Yale University, Cushing/Whitney Medical Library; published under fair use)

Early Alcoholics Anonymous poster, 1930s (image provided by Illinois Addiction Studies Archive; published under fair use)

These images reveal the body of the addict as a site of projection for historically American fantasies about white masculinity’s ability to triumph over nature and circumstance, to pick himself up by the bootstraps. To be enslaved by drugs, they suggest, was akin to being enslaved by the land, an animalistic desire incompatible with a civilized life. Addiction as enslavement requires a coherent self to enslave and thus to free, and this self was white, middle-class, and based largely in and around New England, the center of medical research and treatment for much of America’s history.26 The long nineteenth century saw the development of, in Shawn Michelle Smith’s words, “a middle-class conception of the self as centered in an interior sphere.”27 In the context of the enormous social change of the Industrial Revolution, this nineteenth-century self was defined against exposure to racialized others and lower classes. These interior depths, Smith argues, psychically justified a superior position in the social hierarchy. Addiction naturally raised concerns about the stability of this interior self, meriting intervention from the state.

In the decades following the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, a series of legislations were passed that together shifted responsibility for addicted individuals from doctors to law enforcement. As William White summarizes, these decisions were “strongly influenced by the alleged association between illicit drug use and ‘undesirables,’ (anarchists, radicals, and foreigners).”28 By this time, addiction treatment facilities were an established solution for those who could afford sympathetic medical care and were not targeted by law enforcement. The criminalization of drugs bifurcated the figure of the addict along the lines of race and class, determining whether one would be treated with medical care or punitive action.29 The very illegality of “hard” drugs like heroin disassociates them from white users. The original American addict—the person suffering from an uncontrollable disease—was white, middle class, and understood to be merely lapsing from their fundamental sobriety, as in their ability to Just Say No.

We see this logic persisting today in the message of the book covers considered here. If the opioid epidemic is affecting mainly white people, especially those who until recently were members of the middle class, then it is most easily explained by external circumstances that hinder their ability to rationally resist drugs. In Dopesick, Macy quotes sociologist Shannon Monnat: “When work no longer becomes an option for people, what you have at the base is a structural problem, where the American dream becomes a scam . . . . If the economic collapse was the kindling in this epidemic, the opiates were the spark that lit the fire.”30 There was also a shortage of work during the depression of the 1930s, but this was met with expanding social programs and followed by a period of high economic growth. Our current period of automated or offshore work has severely limited economic mobility for the 62 percent of adult Americans without a college degree, while the social safety net is continually reduced.31 This would reasonably give many Americans a sense that the American dream has indeed become “a scam.”

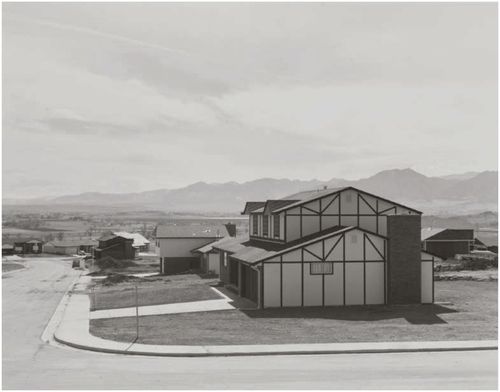

The eerie quality of these book covers aligns them less with the FSA images than with the work of the photographers often grouped under the heading of “New Topographics”: Robert Adams, Stephen Shore, Lewis Baltz, and Frank Gohlke, whose work also questioned the value of the American dream. Exhibited in 1975 at the George Eastman House, New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape presented the built environment—suburban tract homes, factories, parking lots—from an ambivalent, suspicious perspective toward human impact on the land.

On the cover of Brian Allen Carr’s Opioid, Indiana, (2020) the mobile homes of Robert Adams meet the washed-out colors of Stephen Shore.32 The wide, empty streets of Tightrope, Dreamland, and Do No Harm recall Shore’s 2nd Street East and South Main Street, Kalispell, Montana (1974) more than they do the work of Walker Evans. Paul Taylor’s photograph on the cover of American Epidemic could be a nocturne version of Adams’s Tract house, Boulder County, Colorado (1973).33 Both place our vantage point squarely on the other side of the road, pulling the eye down the empty street past a row of suburban homes whose repetition adds to the overarching mood of stillness and passivity. These, we are told by the book’s title, are the “front lines of the opioid crisis”: anonymous suburban homes through which addiction floats freely. In the flatness of Taylor’s homes still lingers the question raised by the photographers associated with New Topographics, that of America as a failed and environmentally unfixable project for which something better may have been lost.

The exhibition appeared in the middle of the economic recession that marked the end of the postwar boom, with rising unemployment and the beginning of budget cuts to social programs. Along with fewer jobs, the growth of automation created an aesthetic of bland repetition that fed a growing sense of alienation and disillusionment. Numbing repetition visually echoes the main feature of drug dependency, and it was in this context that Valium became the highest-selling pharmaceutical in the United States between 1969 and 1982 as an antidote to the unease of modern life.34 After declining following the introduction of Prozac and other antidepressants that target anxiety, prescriptions for benzodiazepines like Valium rose by 50 percent between 2005 and 2015 and were present in 30 percent of fatal opioid overdoses.35

The New Topographics synthesized these themes of social disequilibrium with a nascent environmental anxiety that has since become the dominant theme of the show’s legacy. Lewis Baltz wrote of his subject matter in 1975:

Conceived in expedience for the sole purpose of maximum profit, pathetically dependent on the automobile, these new cities have disposed themselves formlessly along the frontage roads of every interstate highway. Posing an ecological threat which we are only now beginning to grasp, this new human sprawl is also ultimately as alien to urbanism as it is to the land it consumes.36

While culture has certainly begun to grasp ecological threat since Baltz’s writing, we have also grasped a sense of helplessness in the face of it, while the manifestations of climate change continue to surpass the fears of 1970s environmentalists. For contemporary viewers of the New Topographics landscapes, the environmental anxiety Baltz describes has intensified into despair. The visual legacies of the aforementioned photographers intersect with the media spectacle of the opioid crisis at the site of this common despair, characterized by a sense of hopelessness toward the future.

Let’s return to the coal towers dotting the mountains on the cover of Dopesick. Today it is difficult to look at any landscape and not think of climate change, especially for the well-informed target readers of these books. By appealing to our anxiety about climate change via the environmentalist aesthetic of the New Topographics, readers may approach these books prepared for despair, and perhaps with an appetite for it. Whether this allows them to empathize more with the victims of the opioid crisis or simply affirms a conviction that things are hopeless, this framing of the story upholds the sympathy and protectiveness that has historically been reserved only for the white addict.

Climate change is far from the only source of anxiety for the target reader of these books. The feelings of isolation and economic insecurity that Case and Deaton studied in white Americans are not limited to a geographic region. What we see now when we look at rural scenes, the factory town and suburbia, is not what the original viewers of the New Topographics saw.37 This resonates with Lauren Berlant’s observation that many “realist” portrayals of contemporary life from the second half of the twentieth century now feel archaic in their assumed ubiquity of stable incomes (however monotonous that lifestyle might be) and durable attachments. She writes that “for many now, living in an impasse would be an aspiration, as the traditional infrastructures for reproducing life—at work, in intimacy, politically—are crumbling at a threatening pace.”38 Impasse implies a holding pattern, and thus a certain stability that in conditions of instability may seem enviable.

Being “given over” or even, perhaps, “enslaved,” as in the addiction imaginary, connotes the same unproductive stability in the pursuit and evermore delayed promise of numbness. In the context of the declining conditions of social life, addiction suggests a fantasy of reliability—a single-minded, pleasure-focused pursuit—in which to take refuge, whose absorptive rhythms and dramas are more predictable than the ongoing crisis of contemporary life.39 As late-stage capitalism further impedes ways of living, and makes alternatives to it harder to imagine, nonproductive behaviors—what Berlant would call moments of “lateral agency,” such as drug use—become further subject to scrutiny.40 The use of landscapes to signify addiction within the current environmental imaginary suggests that drug addiction could now be everybody’s problem in a way it was not before, because not only does it affect people whom it did not before, but its appeal is easier to understand than it used to be. When addiction is not an isolated incident but a symptom of the culture, then the problem exceeds the representational capacities of the human figure.

W. J. T. Mitchell has pointed out that landscape does something unique: it “effaces its own readability and naturalizes itself” while at the same time it “always greets us as space, as environment, as that within which ‘we’ (figured as ‘the figures’ in the landscape) find—or lose—ourselves.”41 I want to call attention to the fact that landscape presumes a self at all, while addiction has been constructed as a self that is held hostage. In the longstanding American philosophy, the addict who is actively using occupies a subhuman category, physically present but absent where it counts. That a certain essential quality can be nullified by addiction betrays a deep investment in the category of the human as uniquely sentient and agentive.

Epidemics are in many ways products of their historical moment. While journalists demonstrate that the opioid crisis is the result of a series of nuanced factors, the accompanying images do more than just summarize an implicit sense that it is also about declining conditions in which to be sober. Landscape purports to be a “real” place and implicates the viewing subject in relation to it. It does so here, on the covers of this grouping of texts, precisely as the opioid crisis reminds us of the costs of living on American land.

I would like to thank Horace D. Ballard, Emmelyn Butterfield-Rosen, Diane Ahn, and Mariana Fernandez for their generous help and support of this project.

Charles Keiffer earned his MA in art history at Williams College in 2021. He lives in New York City and works at Luxembourg + Co.

- Beth Macy, Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 2018). ↩

- Roland Barthes, “Rhetoric of the Image,” in Image-Music-Text (New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1977), 32–51. ↩

- See, for example, two important methodological sources for this project: Cara A. Finnegan, Picturing Poverty: Print Culture and FSA Photographs (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2003); Emily Hage, “Reconfiguring Race, Recontextualizing the Media: Romare Bearden’s 1968 Fortune and Time Covers,” Art Journal 75, no. 3 (July 2, 2016): 36–51. ↩

- Hage, “Reconfiguring Race, Recontextualizing the Media.” 37. ↩

- Lauren Harms, designer of Dopesick’s cover, interview by author, May 10, 2021. ↩

- See the covers of One by One: A Memoir of Love and Loss in the Shadows of Opioid America by Nicholas Bush (Apollo, 2018); Fentanyl, Inc. by Ben Westhoff (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2019); Do No Harm: The Opioid Epidemic by Harry Wiland (Turner, 2020), Canary in the Coal Mine by William Cooke (Tyndale, 2021); and The Least of Us by Sam Quinones (Bloomsbury, 2021). ↩

- Prior to 2016 the opioid epidemic was seldom discussed outside the public health community. An article in a Canadian journal first designated it as a “crisis” in 201: Meldon M. Kahan, “The Opioid Crisis in North America,” Canadian Family Physician 57, no. 5 (May 2011): 536–39. The first reference in the New York Times was an article in 2013 that mentions “an exploding opioid abuse epidemic” in the United States: Deborah Sontag, “Addiction Treatment with a Dark Side,” New York Times, November 17, 2013. ↩

- Editorial Board, “Drug Deaths Reach White America,” New York Times, January 25, 2016. ↩

- Andrew Cherlin, “Why Are White Death Rates Rising?,” New York Times, February 22, 2016. ↩

- Dan Keating and Kennedy Elliott, “Why Death Rates for White Women in Rural America Are Spiking,” Washington Post, April 9, 2016. ↩

- Kimberly Kindy and Dan Keating, “Opioids and Anti-Anxiety Medication Are Killing White American Women,” Washington Post, August 31, 2016. ↩

- Anne Case and Angus Deaton, “Suicide, Age, and Wellbeing: An Empirical Investigation” (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2015); “Long-Term Trends in Deaths of Despair,” Social Capital Project (Washington, DC: Joint Economic Committee, Senate Republicans, September 2019); Kevin Loria, “‘Deaths of Despair’ Are on the Rise among Working-Class White Americans, New Research Suggests,” Business Insider, March 23, 2017; Ann Brenoff, “White Americans Are Dying from a Surge in ‘Deaths of Despair.’ This May Help Explain Trump, According to Economists Studying Mortality,” Huffington Post, March 23, 2017; Joel Achenbach and Dan Keating, “New Research Identifies a ‘Sea of Despair’ among White, Working-Class Americans,” Washington Post, March 23, 2017. ↩

- Several news outlets reported on the Sackler family behind Purdue Pharmaceuticals, the company that produces OxyContin, who are also well-known museum benefactors, including Patrick Radden Keefe, “The Family That Built an Empire of Pain,” The New Yorker, October 30, 2017; Christopher Glazek, “The Secretive Family Making Billions From the Opioid Crisis,” Esquire, October 16, 2017; and Alex Marshall, “Museums Cut Ties With Sacklers as Outrage Over Opioid Crisis Grows,” New York Times, March 26, 2019. ↩

- Lauren Harms, interview by author. ↩

- Patti Ratchford, interview by author, July 19, 2022. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- The journalism industry platform, Letter.ly reported that 72 percent of New York Times readers have at least a university degree, 71 percent are white, and 91 percent are Democrats: Milos Djordjevic, “25 Insightful New York Times Readership Statistics,” Letter.Ly, March 14, 2021; “In Changing News Landscape, Even Television Is Vulnerable, Section 4: Demographics and Political Views of News Audiences,” Pew Research Center, September 27, 2012. ↩

- Wiland, Do No Harm. ↩

- Maia Dolphin-Krute, Opioids: Narrative, Addiction, Freedom, (Santa Barbara, CA: Punctum Books, 2018), 28. The reference to optimism and “the good life” reflects the influence of Lauren Berlant’s Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), which describes contemporary affects in these terms and also informs my analysis of the opioid epidemic and class difference in America. ↩

- Kyle Vanhemert and Peter Mendelsund, “What Makes for a Brilliant Book Cover? A Master Explains,” September 23, 2014. Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor, (New York: Picador, 1978). ↩

- Beth Macy, Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company That Addicted America, (New York: Little, Brown, 2018), 9. For the lack of geographical specificity to the opioid crisis, see Veronica A. Pear et al., “Urban-Rural Variation in the Socioeconomic Determinants of Opioid Overdose,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 195 (February 2019): 66–73, which concludes that “Regardless of urbanicity, elevated rates of prescription opioid overdose were found in more economically disadvantaged zip codes.” ↩

- Finnegan, Picturing Poverty, xi. ↩

- Corky Siemaszko, “Ohio City Releases Shocking Photos to Show Effects of Poison Known as H,” NBC News, September 9, 2016; Alice Park, “The Story Behind the Viral Photo of an Opioid Overdose,” Time, January 24, 2017. ↩

- Skelly, “Skin and Scars,” 2. ↩

- George Wheelock Grover, Shadows Lifted: Or, Sunshine Restored in the Horizon of Human Lives. A Treatise on the Morphine, Opium, Cocaine, Chloral and Hashish Habits. (Chicago: Stromberg, Allen & Co., 1894), 9–10. Grover’s statistics are likely exaggerated. ↩

- See Colin Woodard, American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America (New York: Penguin Books, 2012). Woodard describes New England or “Yankeedom” as uniquely concerned with self-governance, responsibility, and education, dating back to Puritan roots and making “sobriety” a particular area of concern. ↩

- Shawn Michelle Smith, American Archives: Gender, Race, and Class in Visual Culture (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 67. ↩

- White, Slaying the Dragon, 151. ↩

- “Punishment and Prejudice: Racial Disparities in the War on Drugs,” Human Rights Watch 12, no. 2 (March 2000), “Relative to population, black men are admitted to state prison on drug charges at a rate that is 13.4 times greater than that of white men.” ↩

- Macy, Dopesick, 151–52. ↩

- Anne Case and Angus Deaton, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020). ↩

- Brian Allen Carr’s Opioid, Indiana is the sole work of fiction in this study, but it appears concurrently with the others and indicates the standardization of this marketing strategy: Carr, Opioid, Indiana (New York: Soho Press, 2019). ↩

- John McMillian, American Epidemic: Reporting from the Front Lines of the Opioid Crisis (New York: New Press, 2019). ↩

- Kimball P. Marshall, Zhanna Georgievskava, and Igor Georgievsky, “Social Reactions to Valium and Prozac: A Cultural Lag Perspective of Drug Diffusion and Adoption,” Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 5, no. 2. ↩

- Eric C. Sun et al., “Association between Concurrent Use of Prescription Opioids and Benzodiazepines and Overdose: Retrospective Analysis,” British Medical Journal, March 14, 2017; Rhitu Chatterjee, “Steep Climb In Benzodiazepine Prescribing by Primary Care Doctors,” NPR, January 25, 2019. ↩

- Lewis Baltz, “The New West,” Art in America (April 1975). ↩

- Curator Britt Salvesen notes that in 1975 the majority of the reviews focused on stylistic concerns, with only one calling the show “ecologically based social criticism.” Britt Salvesen, Alison Nordström, New Topographics, 2nd ed. (Göttingen, Germany: Steidl, 2010). ↩

- Berlant, Cruel Optimism, 5. ↩

- This is not to suggest that drug addiction is a pleasurable experience, but to acknowledge that drugs are addictive because they repeatedly activate and then deplete the brain’s pleasure centers. ↩

- Lauren Berlant, “Slow Death (Sovereignty, Obesity, Lateral Agency),” Critical Inquiry 33, no. 4 (2007): 754–80. ↩

- Mitchell, Landscape and Power, 2. ↩