From Art Journal 82, no. 1 (Spring 2023)

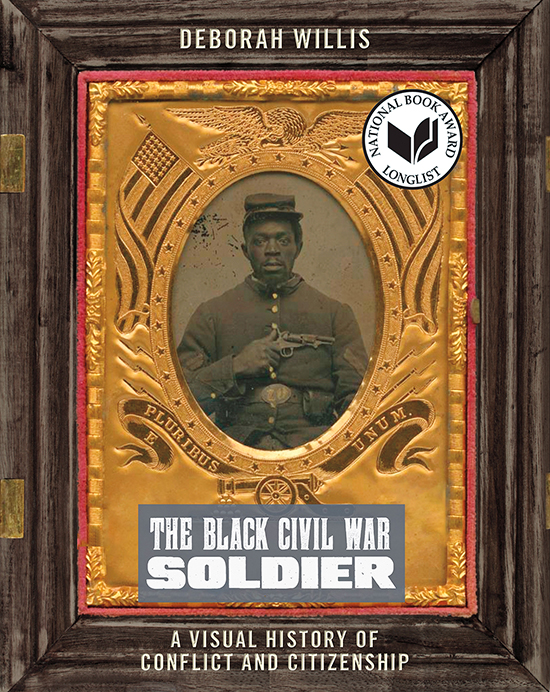

Deborah Willis. The Black Civil War Soldier: A Visual History of Conflict and Citizenship. New York: NYU Press, 2021. 256 pp.; 99 b/w ills. $35.00

In 1976 poet Lucille Clifton published a memoir that opened with an interaction that even now seems familiar, almost fifty years later. She had placed a newspaper ad seeking relatives of the Sayles family. A white woman responded, “Well, my maiden name was Sayles, I say. What was your father’s name? she asks… . Samuel, I say. She is puzzled. I don’t remember that name, she says. Who remembers the names of the slaves?”1 Clifton uses her investigation of a fragmented historical record to ground her own family history, the story of the descendant of Dahomey women, including her great-great-grandmother Caroline, who was kidnapped from the West African kingdom where she was born and enslaved in Virginia at the age of eight. Generations is thus a recovery narrative that asserts the presence of Clifton’s family, and Clifton herself, in two centuries of American life. In doing so, she invites readers to remember the names of enslaved people, and their descendants, but also invites readers to see these historical figures as complex humans navigating social upheavals on both micro- and macrolevels.

Clifton anchors the memoir with family photographs, around which she drapes a quilt stitched from patches cut from stories received on paper and from historical documents. Reprinted on the creamy rag paper of a paperback trade book, the likely sharp details of the originals blur into washes of gray and Black. A young man sitting next to an elderly woman with a small bonnet, a young woman standing perfectly erect in a photography studio wearing a dress from the 1880s, the direct gaze and jaunty moustache of a man shown in a small circular headshot. Clifton does. not analyze or even extensively discuss these photographs, but they are not just illustrations either. In the book’s final pages, she writes, “Things don’t fall apart. Things hold. Lines connect in thin ways that last and last and lives become generations made out of pictures and words just kept.”2 Remembering the names is only part of the work—it is also the practice of recording and conveying the particular ways that individuals navigated constrained circumstances. Immersion in the narrative Clifton assembled provides a sense of this, but by including the photographs, she invites readers to become part of the work. What Barthes would call a punctum, the detail in a photograph that captivates or “wounds” the reader, Clifton might call a point at which a line connects.

Such lines connect throughout The Black Civil War Soldier: A Visual History of Conflict and Citizenship, in which Deborah Willis crafts a history “out of pictures and words just kept.” In her career as a photographer, curator, and art historian, Willis has long defied easy categorization. With this book she again challenges the borders of scholarly disciplines, as well as distinctions between academic and public-facing work, with her production of a “visual history” populated chiefly by archival photographs juxtaposed with transcriptions of primary source texts. The result is a book with a distinctly curatorial sensibility, a fact that reflects the origins of this project in the 1980s, when Willis served as curator and collections coordinator for an initiative that would eventually become the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. As she traveled the country, meeting with collectors and families to develop a collection for a future museum, she encountered photographs of Black Civil War soldiers, and family stories that honed her ability to read what she describes as “resistance to slavery” in those images. This book is an attempt to honor the lives of the soldiers whose bodies were kept in the daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, tintypes, cartes-de-visite, and stereoscopic prints that Willis encountered on an archival journey spanning four decades.

At first glance, the result looks surprisingly like a documentary history of Black soldiers during the Civil War. In chronological chapters dedicated to a single year of the war, with a final chapter focusing on the memorialization of soldiers during Reconstruction and beyond, Willis provides succinct historical context, jumping in occasionally to frame the images and documents that take up the bulk of the book. Readers prepared for a visual history may be surprised to see how much space Willis dedicates to transcripts of primary source texts—journal entries, letters, pension records, legal documents, newspaper articles.

Placed in conversation with the photographic archive Willis has assembled, these sources provide access to the inner lives of soldiers and their loved ones, in particular “to resurrect their views about the war and the circumstances in which they found themselves” (18). The chronological organization, extensive use of textual sources, and Willis’s synthetic historical framing would make this book accessible to those without significant knowledge of the Civil War or the history of photography. It also could bring the faces and voices of Black Civil War soldiers into high school and college classes, as well as to participants in community organizations and other non-academic audiences.

Readers invested in the study of Black visual culture might find themselves immersed in a very different book, one that draws on a vibrant scholarly conversation about the ways that Americans have used images and documents to remember—or forget—Black struggle. Building on work by scholars such as Tina Campt and Saidiya Hartman, Willis raises questions about what photographs did for Black soldiers and their loved ones, and how photographs shaped popular memories of these men, even long after their deaths. Photographs are both representations of a particular moment in the life of an individual, and also objects that continue to circulate well beyond the moment they documented. Willis invites readers to see the images she has assembled as portals into larger social worlds—both the lived experiences of Black soldiers extending well beyond the frame of the photographic field, but also how the circulation of these images shaped popular memories of Black soldiers and the role they played in the Civil War. While Willis is a skilled close reader of images, here she focuses her attention on the development of a conversation across and between primary sources—both visual and textual. The result is a kind of “collective portrait,” a term first used by Willis in her 2013 book with historian Barbara Krauthamer, Envisioning Emancipation, where they argued that both free and enslaved Black Americans used photography to stage and participate in a conversation about the roles they played in transforming the social and political landscape of the nation.3 Here Willis revisits similar territory, this time focusing more specifically on the ways that photographs of Black Civil War soldiers powerfully indexed their subjects’ resistance to slavery. Soldiers used photographs to communicate with loved ones, and to visually insert themselves into national conversations about citizenship and belonging. As Willis writes, “having a photograph taken was a self-conscious act, one that shows the subjects were aware of the significance of the moment and sought to preserve it” (10). By collecting and displaying these images, Willis thus offers readers a kind of access to a series of intimate moments in which the soldiers’ desires were visibly on display, but also honors the wishes of the soldiers themselves in their desire to be remembered.

The development of a collective portrait is a useful strategy because of the fragmentary nature of the archive that Willis is investigating. Of the some 180,000 Black soldiers who fought in the Civil War—roughly 10 percent of Union troops—only a small fraction of those men ever sat for photographic portraits, and as Willis’s archival journey demonstrated, prior to the last four decades, few of those images made their way into traditional archival collections (116). Even fewer photographs were taken of the thousands of enslaved men who served masters defending the Confederacy, though as Willis argues, those that are extant offer important insights into a set of “perplexing relationships” (44). For this reason, Willis focuses primarily on soldiers who fought on the side of the Union, but even then, of the many soldiers whose portraits are identified in her book, many are identified with general labels: “orphans,” “a soldier and his wife,” or “contraband.” In some cases, Willis has access to photographs with clearly identified subjects, as well as textual documents in which those subjects reveal their personal views on the conditions of military service for Black men. Letters between Frederick Douglass’s son Sergeant Major Lewis Douglass and his fiancée, Helen Amelia Loguen, help readers to read more deeply into two formal portraits of the lovers (110–14). But many of the other photographs found in the book lack such an obvious pedigree; Willis often contends with images that have no provenance, or textual sources produced by or discussing soldiers of whom no known photographs exist. Rather than delving deeply into the biographies of Loguen, Douglass, or any of the other figures who populate the book, Willis provides their images or excerpts of the textual records they left behind to build a collective portrait that reveals what the status of soldier and the daily experiences of soldiering meant to Black Americans at this time.

The potential pitfall of this approach is that it can reinforce the symbolic power of these images at the expense of the kinds of intimate views that Willis hopes to resurrect. The problem is not simply that Black Civil War soldiers are often missing from popular depictions of the war, as Willis argues in the introduction, but also that the symbolic power of these photographs can overdetermine viewers’ responses. Under these circumstances, the complexity of individual experiences can collapse, leaving viewers with a kind of surface reading: the Black soldier as a token of a familiar type. Without care, a collective portrait could start to resemble a photographic composite, a method pioneered by British eugenicist Francis Galton in the late nineteenth century. By exposing a succession of photographic plates to produce a single print, Galton could create a visual average of similar images—a strategy he used to produce composite portraits that highlighted the shared features of criminals or developed a visual racial “type.”4 But where the composite method results in the production of a single, often eerie image that is a portrait of everything and nothing at once, they are not easily disassembled into their component parts. In contrast, the collective portrait Willis assembles can call attention to both visual patterns, without losing the reader’s access to the idiosyncrasies of any particular image or historical actor pictured within.

The structure of Willis’s book invites synthetic observation—looking across and between texts and images—but at the same time, the inclusion of such a wealth of primary sources invites readers to bring their own interpretive skills to the work of observation. The uncannily fine grain produced by nineteenth-century wet-plate photographic processes makes soldiers portrayed in these pictures feel radically present to contemporary viewers, highlighting any particular soldier’s distinctive individuality in the direction of his gaze, the angle of his posture, or the placement of his hands. Both as documents of intimate experience and as symbolic representations, these photographs exhibit a representational tension, one that becomes evident as viewers engage with the collective portrait and the distinctive texts and images that comprise that portrait. Even when readers are instructed to see how lines connect across the primary sources included in the book, readers may find themselves in unexpected moments of intimate engagement with a particular object or document. The methodological interventions of this book, and in particular the way that Willis invites readers to engage with the historical record, invite the interpretation of this book as a pedagogical project. As she guides readers through the text, Willis invites us into a particular way of seeing, a practice of noticing when the subjects of photographs gesture beyond the edges of their frames.

Both Willis’s and Clifton’s books are framed around failures of memory, not just the problem of remembering the names of enslaved people and their descendants, but a bigger loss of awareness—or in some cases refusal to recognize—the ways that Black Americans asserted their selfhood in the face of significant resistance, thus propelling dramatic social transformations. In each of these texts, the response to such losses is the assembly of a narrative from words and texts, just kept, a process that reminds us that losses of memory can result from the absence of documentation, but also from a lack of narrative structure that helps the flood of historical documents make sense. As Clifton assembled her raw materials into prose, poetry kept creeping in, resulting in a memoir in which readers must be part of the process of assembly. Unlike a historical monograph, she does not offer clear transitions or conclusions or a summary of argument, and instead readers are left to make the imaginative leaps for themselves. As she reminds us in the book’s first pages, these leaps have consequences and may reflect our own subject positions or backgrounds: “She is puzzled. I don’t remember that name, she says.” Who and how we remember is political work.

Reading Willis alongside Clifton makes the poetry of The Black Civil War Soldier more evident. Though Willis utilizes an apparatus drawn from historical scholarship, the body of her work more closely resembles an assemblage. The author’s curatorial perspective is visible in the particular order and assembly of documents and “photographs that [hold] old and new stories” (212), but still, it is hard not to notice the frames of the discrete images, the edges of the page on which these documents were printed. There are many gaps between the texts and pictures that Willis has arranged, and rather than easing our way across those junctures, she leaves them there as a reminder that memory is work. The gaps, the edges, the points where the subject of a photo gestures beyond the frame are reminders that readers must see the lines of connection—even those that lead through violence and pain—and take responsibility for the collective labor of making and holding memory.

Katherine Lennard is a US historian who studies the material culture of race in the wake of the Civil War. She is the inaugural Abbott Lowell Cummings Fellow in American Material Culture at Boston University. Her monograph, Manufacturing the Ku Klux Klan: Robes, Race, and the Birth of an Icon (forthcoming from the University of North Carolina Press), examines the garments worn by multiple generations of Klan members to track changing ideas about the Klan’s role in American social life.

- Lucille Clifton, Generations: A Memoir (New York: Random House, 1976), 12. ↩

- Ibid., 275. ↩

- Deborah Willis and Barbara Krauthamer, Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2013), 20. ↩

- Alan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October 39 (Winter 1986): 47–52. ↩