Contemporary Projects features original projects driven by artists, designers, or curators, highlighting diverse, critical forms of knowledge directly produced by art and design practices.

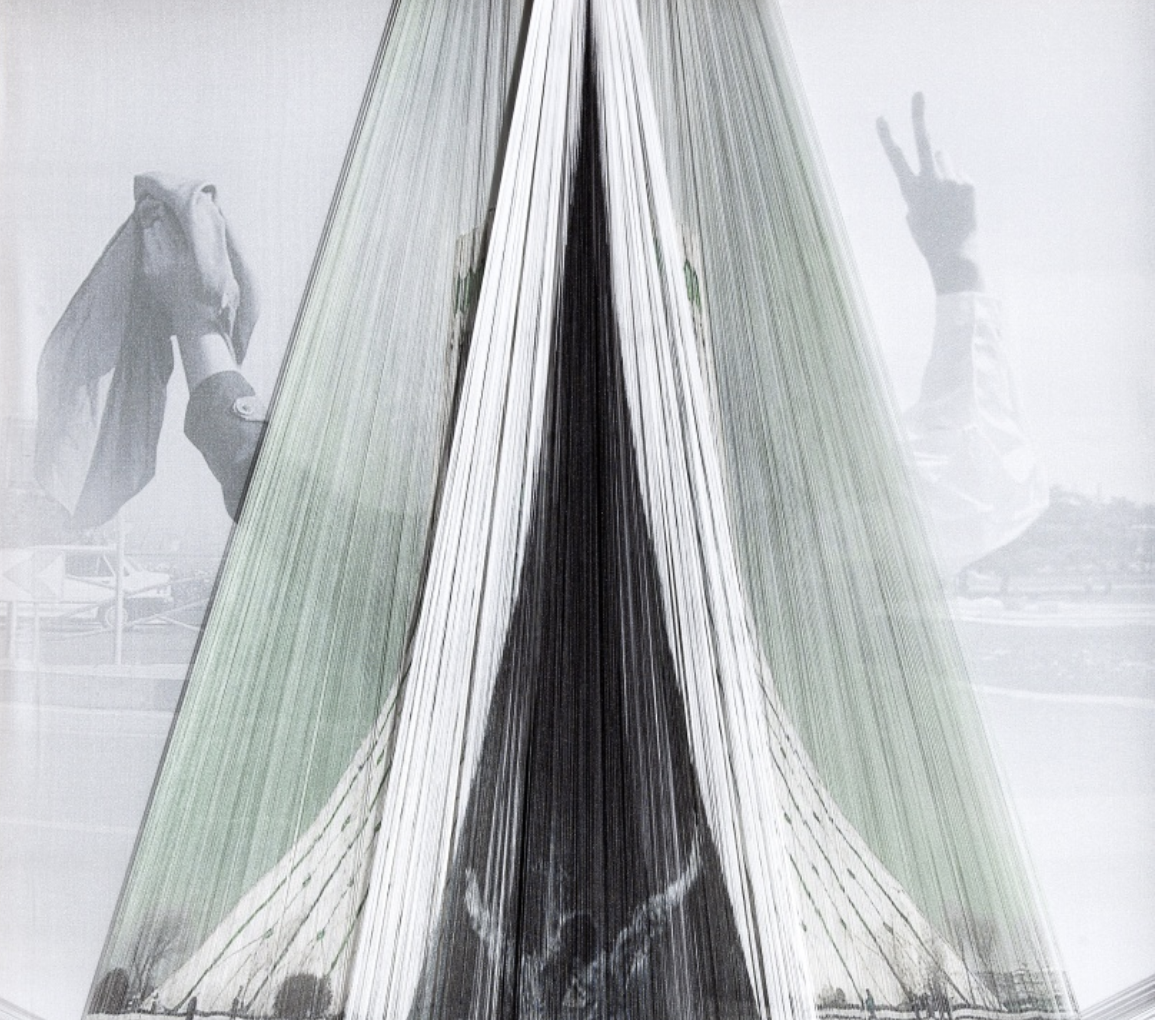

Threads of Freedom, is a simultaneous weaving together and unwinding of stories of Iranian women who take photographs of themselves and share them on social media in an effort to liberate their bodies from governmental discrimination and control. I print these images on fabric and deconstruct them by hand, spending hours in an uncomfortable and exhausting posture while I focus on the threads. This process is a form of protest, a way to resonate with the struggle, to participate by reweaving our stories, and in so doing, amplify the significance of Iranian women’s actions and to echo their message. Unreclining unweaves and recombines four photographs Iranian women took of themselves in the streets of Iran. The photographs depict the women after they have removed their headscarves in front of the Azadi Tower in Tehran while making the victory symbol with their hands. For an Iranian woman, removing one’s scarf and revealing one’s hair in public is a crime. In all of these photographs, the women turned their faces away from the camera to protect their identities. The Azadi Tower is a monument that has significant implications in Iranian culture. It has been the site of many events and protests throughout history. Unlike more phallic-shaped towers, the gracefully ascending lines and form of the monument hold space and invite entry, evoking fabric, flowing out to us like a mother’s skirt. Unreclining mimics the architectural resonance of the tower and emphasizes the verticality of the women’s poses and aspirations. These photographs not only challenge representations of women as docile, domesticated, and typically horizontal or reclining, but they also reclaim the physical spaces, streets, and public places that belong to them—and that they have been historically excluded from for nearly fifty years.

Throughout history, women have had a complex relationship with making and consuming fabric; fabric was utilized to simultaneously conceal, beautify, and objectify women’s bodies. For the last four decades, the Islamic government in Iran has constructed a form of state and religious identity which forces women to fully cover their bodies and hair to embody conservative Islamic values; to do otherwise is illegal. In September 2022, a young Iranian woman was arrested in Tehran by the morality police for the crime of not wearing her headscarf properly. Mahsa Amini, who was visiting Tehran, was separated from her family in the street and was taken to a detention center, where she went into a coma and later died in the hospital. The pressure and fear of being arrested by the morality police has overshadowed the everyday lives of Iranian women for many years. In a country where you may be arrested for being in public without a hijab, holding the hand of or kissing a loved one in public, or going to a gathering that includes both men and women, it can feel impossible for Iranian women, such as myself, to feel safe inside or outside of our homes. The tragic death of Mahsa Amini was a moment in which our anger washed away our fears, reunified us, and shaped the Women, Life, Freedom movement.

After this agonizing incident, women have been coming to the streets, removing and brandishing their headscarves and burning them, or cutting their hair. These acts of protest do not end in the street; women continue practicing civil resistance in the virtual space by sharing photographs of themselves. While women are aware of the danger inherent in sharing their images and the risk of being arrested, in the past few months they have regularly shared photos as a political act, resulting in a proliferation of images of brave young Iranian women across social media. These actions are their attempt to free their bodies from an oppressive system of representation and have created a web that connects not only Iranian women but women around the world. As I currently reside outside my home country, I find myself overwhelmed yet empowered by the images that connect us and weave our untold stories together.

Threads of Freedom enables me to be engaged with women living in Iran who are immersed in this movement, allows me to amplify messages of protesters, and highlights the cultural, social, and political significance of women’s resistance in Iran. In Threads of Freedom, the digital images of protest are printed on silk, then mixed, layered, deconstructed, and reconstructed through hours of tedious work to pick apart and reweave them. I carefully separate the threads to dismantle the fabric to reveal or cover the bodies and spaces, and to redefine traditional entanglements between women, fabric, and representation. The silk threads are strong, lustrous, and elegant, like the subjects in the images, and help characterize the material flows of the digital images that carry the message of brave Iranian women who believe in the “Dawn of Victory.”

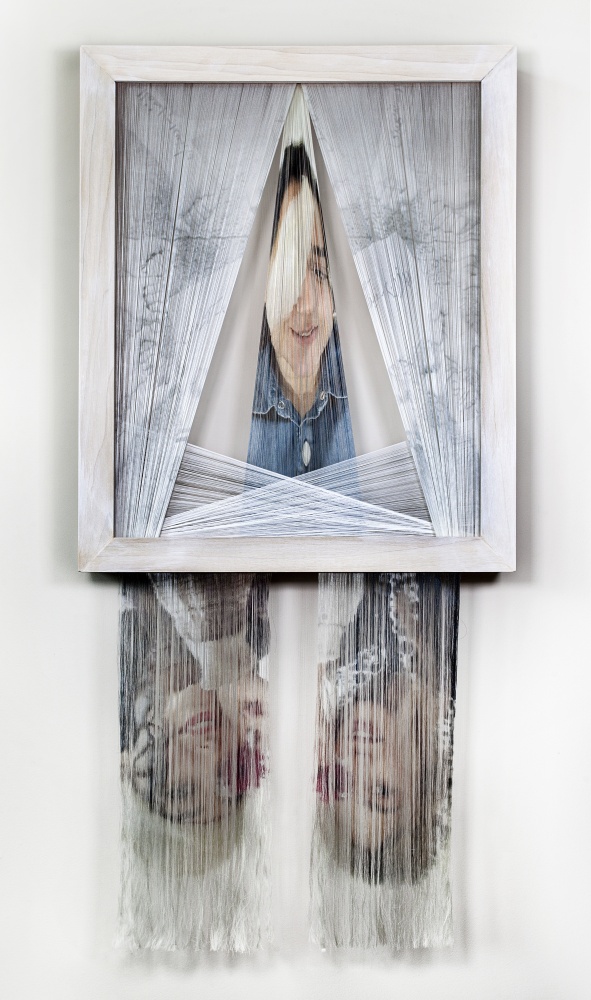

In Unwound, I incorporate selfies of Iranian women who lost their eyesight after being shot by security forces during the protests. In these selfies, women reveal their faces while holding a flower, object, or piece of writing in front of the injured eye. Injuries are simultaneously an unweaving of the body and the weaving of a story into a body. The body, in turn, tells that story. The threads of these women’s stories create a tapestry of a vision for the future. In the center of the frame, I positioned a selfie of Nadia. The photograph shows her with a bandage on her eye and a smile on her face. The faint image framing Nadia is a photograph taken by schoolgirls making fists with the names of protesters who lost their lives written on their wrists. Moving the threads away from Nadia’s image opens a space of appreciation, acknowledgment, and respect for a woman who lost her sight but became a messenger of a vision of freedom. The threads that hang from the frame show two smiling women, each covering an eye with a flower. They show no signs of fear or weakness, instead embodying elegance, courage, and bravery. Their image aligns beauty and feminine strength with defiance and makes the violence palpable by covering the site of injury. The threads that comprise these two images flow below the frame, emphasizing the women’s desired escape from the constructed boundaries of material, social, and political productions.

In Threads of Freedom, I focus on how Iranian women want to be represented by using their images, laden as they are with intent, story, and risk. In Threads of Freedom, fabric does not cover women’s hair or body; instead, it becomes a surface that reveals women’s bodies, and the threads of those fabrics reweave their shared stories.

Mona Bozorgi is an Iranian interdisciplinary artist-scholar who lives in the US. Bozorgi’s work focuses on inclusive representation and explores the performative nature of photography as an entanglement between materials and discourses. Bozorgi is Assistant Professor of Photography at Florida State University. She is also working on her doctoral dissertation titled Selfie-ing: Apparatuses of Bodily Production, at Texas Tech.

CAA and Art Journal Open would like to acknowledge that Mona Bozorgi and Art Journal Open‘s Editor-in-Chief, Grace Aneiza Ali, are both employed by Florida State University. This contribution to AJO was commissioned and edited by AJO’s former Editor-in-Chief, Nicole Archer.