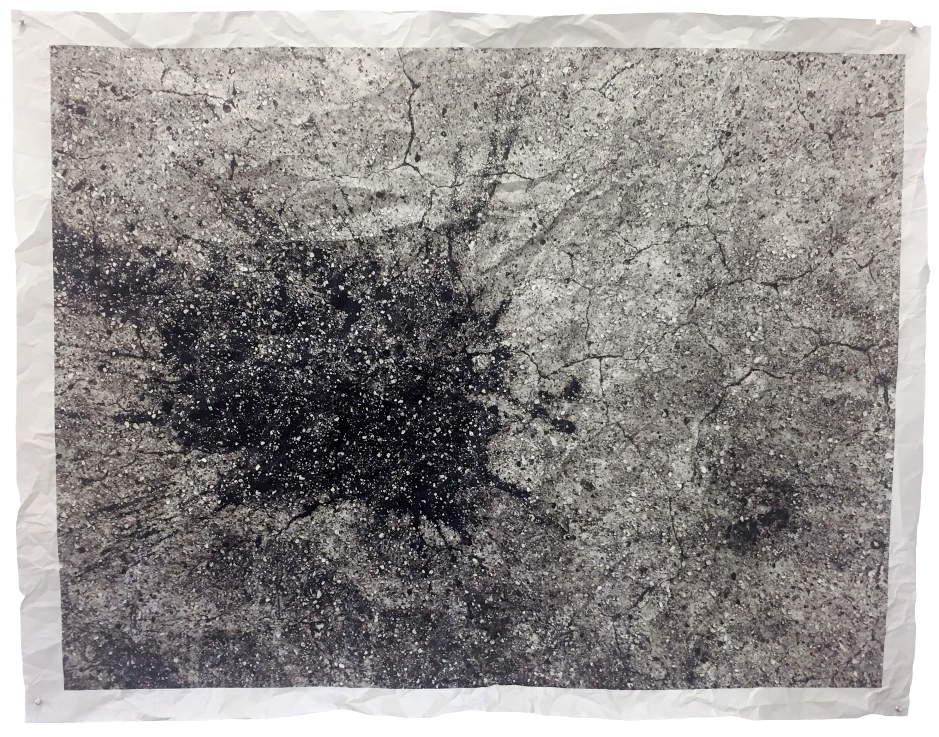

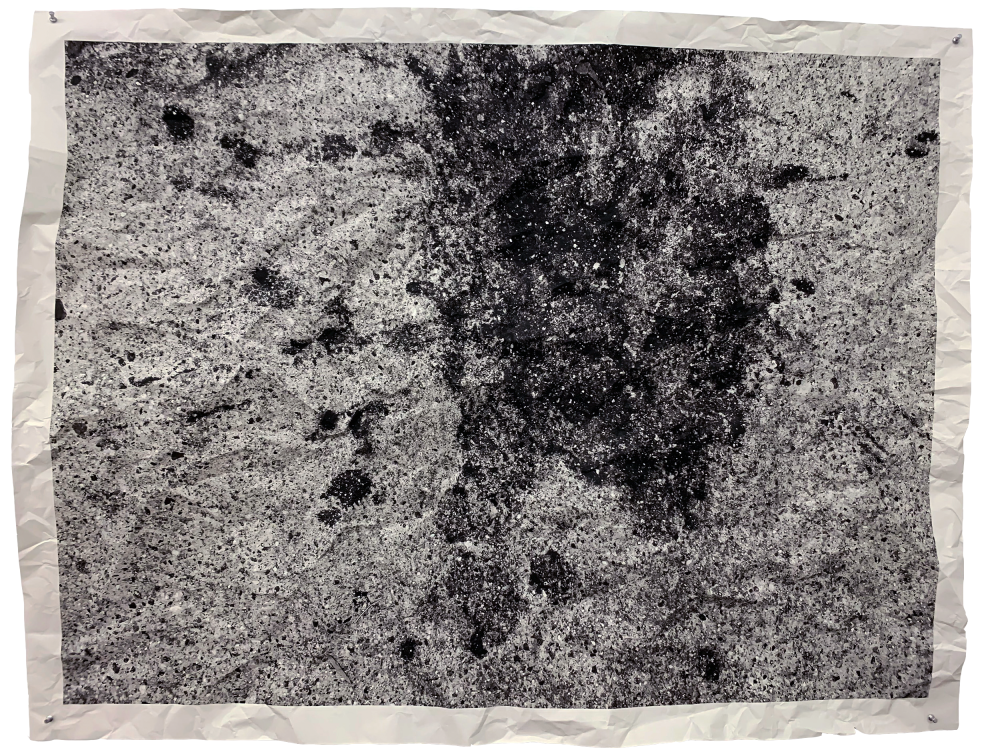

Susan Silton invites readers to download this image here. Print at preferred size, crumple the paper, and open the image back up as much as desired before pinning to wall.

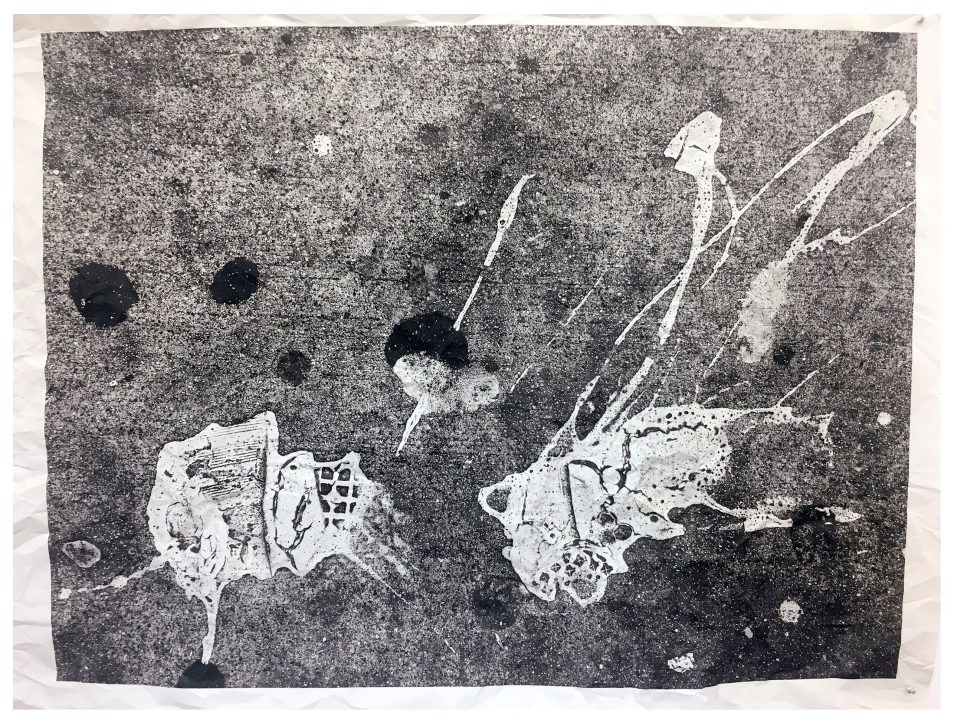

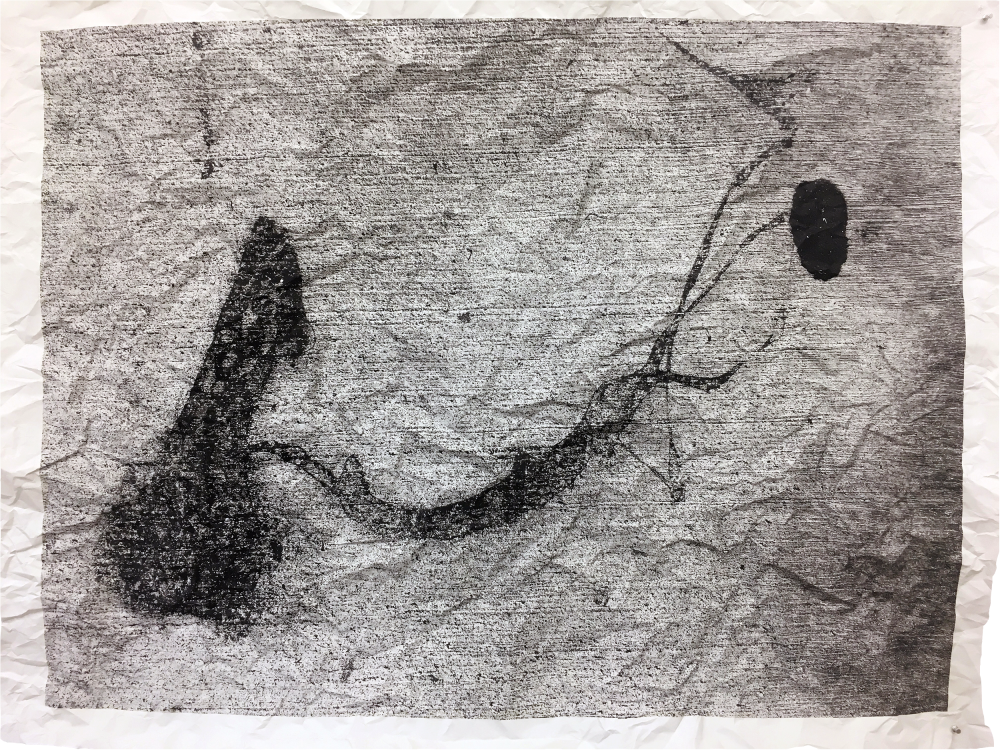

In 2018, Los Angeles-based artist Susan Silton, reeling from what she experienced—what so many of us experienced—as “the emotional, bodily response to Trumpian presence and policy,”1 frequently found her gaze oriented towards the ground. For Silton, “humanity was arduous to look at.”2 During (and since) that time, as she walked the city, instead of looking directly at people, she often found herself observing their leakage: “ordinary stains in the cement, the detritus of our walking, and of our spilling, and of our bodily excretions—the evidence of our being.”3

These traces of bodies moving through urban space ceased to divert Silton’s attention from sociopolitical reality—they clarified it. For Silton, the stains embedded in or on the ground became quasi-pareidolic metaphors for the stains of history, of the current political moment, of the blemishes and disturbances yet to come.

For the last five years Silton has been documenting these stains, printing them as large-format photographs which she then offers to curators or collectors to crumple, fold, or otherwise leave their mark. When exhibited, the photos are often pinned directly to the wall, leaving the paper exposed and making its folds and wrinkles more apparent—reanimating the dynamic materiality of the sidewalks in Silton’s images. What results is the facilitation of a looking that replays Silton’s own. Details of streets once so banal as to be invisible are choreographed into poetic significance. If only fleetingly, cracks in the pavement, gum, splatters of paint become “little ciphers to moments that we can’t quite totally recapture but at least have a point of entry into.”4

The stain of . A stain on . (2018–) begins as an embodied, affective response and ends as a material negotiation. In Silton’s words, she had “recoiled in the face of a novel and ongoing culture of political punishment, of othering and scapegoating, of inflammatory rhetoric and dehumanization that reached new lows during the Trump administration.”5 Silton mobilizes her personal discomfort in order to return to the site/sight—the contradictions and conflict—of that recoiling. Importantly, Silton continues to participate in the social choreography of urban space, cataloguing her visceral responses to the limits on the body and sociality imposed by heteronormative, state, and otherwise oppressive structures. Her oeuvre attests to a keen attunement to the performative, collective modes of making, voice, and other modes of inscription.

Silton’s artistic practice unfolds within a spatiality akin to both Hannah Arendt’s “space of appearance [which] comes into being wherever men are together in the manner of speech and action”6 and Irit Rogoff’s taking up of the term. Rogoff’s space of appearance, which like Arendt’s, is both the site and nature of political action, occurs through an ephemeral mutuality based not on identity or reified spaces of political-cultural power, but in the ebbs and flows of “a related reading of actions and of the fantasmatic subjectivities projected through these actions.”7 Rogoff is particularly drawn to Arendt’s siting of power outside its legitimized modes, structures and participants. This possibility affords a reconceptualization of art as “cultural participation, rather than as a form of either reification, representation, or contemplative edification . . . by seeking out, staging, and perceiving an alternative set of responses.”8

Recalling the “speech and action” that brings about the space of appearance, Silton puts focus on “[t]hat relationship (between words and actions),” which the artist credits as having “guided my entire being—it was just a question of finding the right avenues for expression.”9 As with Rogoff, participatory performativity is the generative force of Silton’s multimodal, searching work linking the political to the artistic. Despite its “final” form as work hung on a wall, The stain of . A stain on . remains within a lineage of performative artwork—in Silton’s practice and beyond—that disturbs discrete experience and creates new collectivities. Amelia Jones has written on Silton as a post-urban subject, queering both psychic and material spaces via the creation of a “complex space of meaning” that collapses distinctions between artwork, exhibition space, viewer, artist. In an analysis of Silton’s 2001 installation hemidemisemiquaver, a video installation of “images of urban life that move just too fast to be seen and comprehended fully,” Jones situates Silton in the Foucauldian heterotopia of Los Angeles, among other artists whose practices speak to their ambiguous, disorienting senses of self and space, intervening both in public life and our understandings of it.10

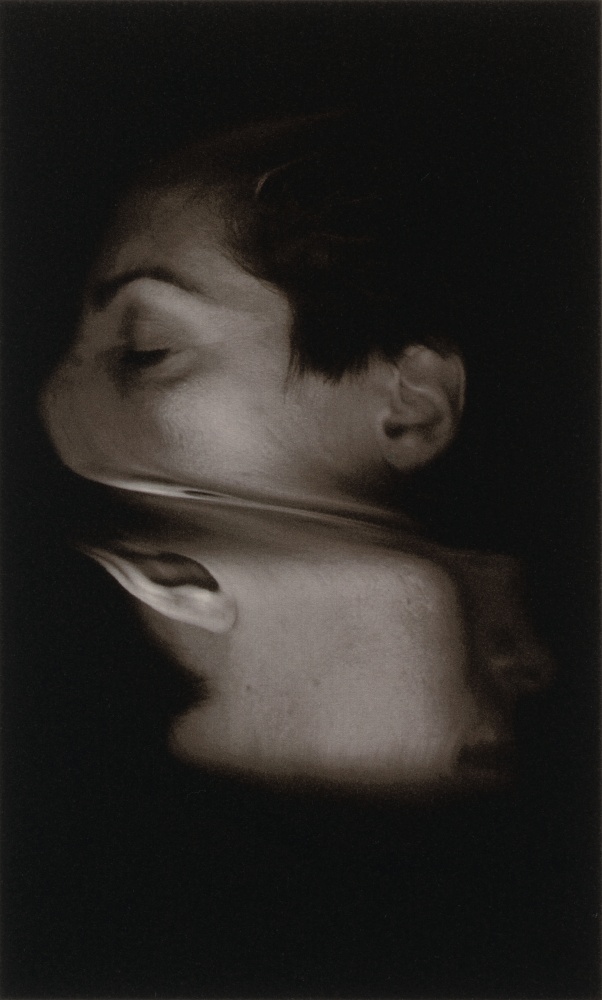

Self-Portrait #4, 1995, giclée print on Rives BFK, 12.5 x 9.5 in. (image © and provided by the artist)

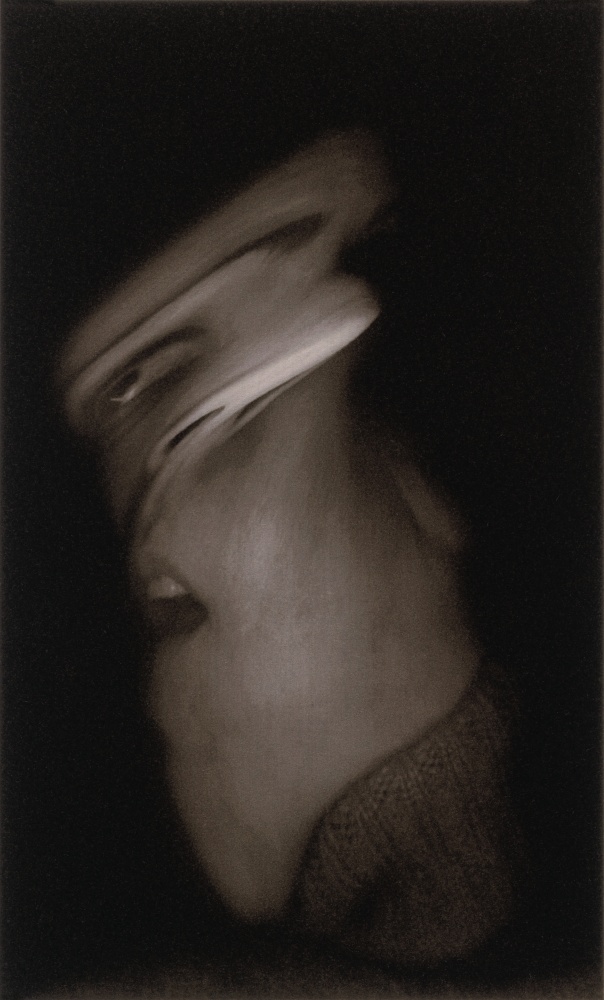

Self-Portrait #9, 1995, giclée print on Rives BFK, 12.5 x 9.5 in. (image © and provided by the artist)

Other early works attest to the endurance of Silton’s preoccupation with troubling subjectivity. The series mutatis mutandis (1994) uses stereoscopes and other visual technologies to grapple with the instability of perception, in particular “the perception of lesbian as mutant, mutation being both anomalous and often necessary to the survival of a species.”11 The title is medieval Latin, translating to “with things changed that should be changed.” In the desktop-scanner–produced Self-Portraits (1995), Silton’s face is distorted by her own bodily manipulations against and with the machine to “consider [her] own mutated selves”12 and the blurred, cyborgian nature of subjectivity.

Silton has continued to develop these poetic meditations on the nature of subjectivity that simultaneously include and exceed the body. In this way The stain of . A stain on . is not simply addressing a personal state of political disappointment, but implicates a society with its figurative head hung low, eyes trained on the ground without even seeing its stains. Silton’s belief that art is a form of cultural participation serves to disturb sedative fantasies of fixed political positions.

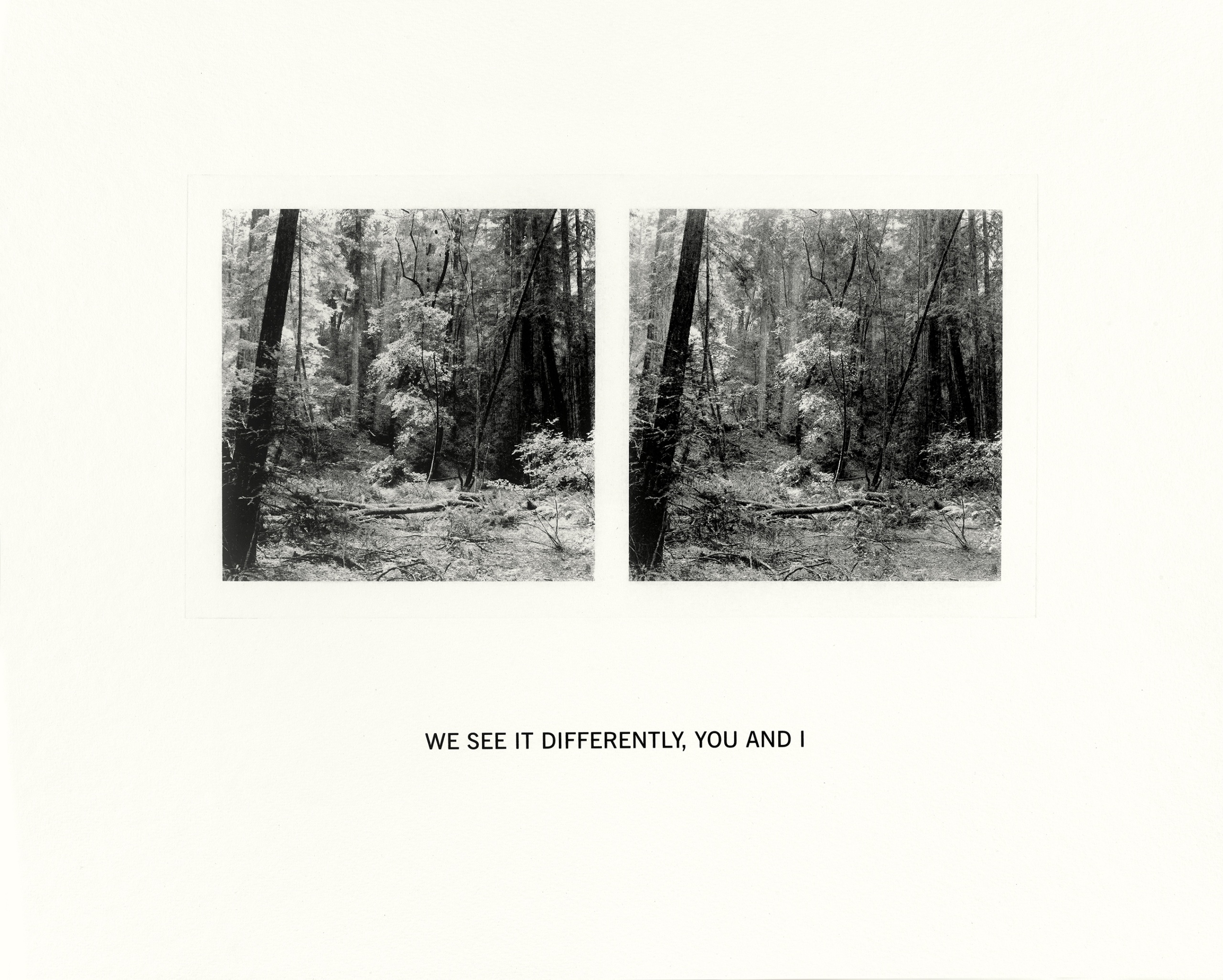

Rogoff advocates for a different kind of looking away, one that shifts the attention from institutions to the relationships between people, the places, and things they make. She asks, “What is it that we do when we look away from art by producing such a ‘space of appearance,’ by attending to the circulation of meaning which passes between us and constitutes a ‘we’?”13 And again, our gaze is diverted towards an itinerant convergence of meaning. Silton’s WE, first exhibited at Los Angeles’s Luis de Jesus Gallery in 2020, is a suite of sixteen pairs of photo-etchings depicting the Armstrong Redwood National Forest. Below each pair of photos is a variation of the phrase “We are seeing it differently, you and I,” written in one of the sixteen possible tenses of the English language. Each print offers two images that first appear identical, but on closer inspection are not. Between two images of the same small clearing, for instance, the trees’ shadows have lightened, but not shifted. And so across the series these modifications alter our perception of the forest’s density, the time of day the photo was taken, and the pictured season. Subtle shifts bring the still forest to life and speak also to the life that marked this forest: Armstrong and its surroundings became known as the “Gay Riviera” in the 1970s and continues to be an important locale of queer culture. Since Silton’s photos were taken, Armstrong has been severely burned by wildfire—adding to the ruination wrought by devastating floods, changes in the tourism and travel industry, public policy, and the AIDS crisis. Silton’s gestures, seemingly slight in comparison to the enormity of these societal ills, nevertheless recall that there always is a history, and that “places are processes, too.”

The final element of WE consists of a short story Silton commissioned the writer Dana Johnson to write, printed and framed in the same manner as the sixteen sets of etchings, and installed it on its own wall at Luis de Jesus. During the exhibition’s final weekend, Silton and Johnson read the story aloud, line by line, one after another. The exhibition’s physical processes of inscription—whether physical (photo intaglio prints, serigraphs, a boxed set), institutional (wooden frames, vitrines), or relational (with Johnson, the master printer Pascal Giraudon, the viewer)—trace and produce the spaces of appearance.

Silton’s sensitivity to how perception might orient us within a pluralist, chaotic society resonates with Arendt’s second critical element of her conceptualization of the public realm, what she called “common sense.”

This same sense . . . fits the sensations of my strictly private five senses—so private that sensations in their mere sensational quality and intensity are incommensurable—into a common world shared by others. The subjectivity of the it-seems-to-me is remedied by the fact that the same object also appears to others though the mode of its appearance may be different.14

Thus we might reconsider the limits of our individual experience as the catalyst for collectivity. In this endeavor, Silton offers a sensuous transparency of process, a risky, tender rigor that has resonance far beyond a single body, or art and its institutions. A stain, or the slightest change in light, exposes all that’s at stake in the spaces we share, in the exchange of words or glances, between “speech and action.” Silton reorients our perspective on our shared world, so that we might see that the space of appearance less as perilous than imperiled. Still, its contingency, and ours, inscribe for us possibility’s promise.

ADDENDUM

In late March 2023, Silton invited me to walk with her in Downtown Los Angeles. We met in Little Tokyo and walked south through the Arts District to the Flower District, stopping at the building in which she lived and worked in the 1980s. All along our route she paused to photograph stains she noticed on the ground beneath our steps.

We looped back to Little Tokyo and paused in front of Toriumi Plaza, a multiply stained site. Just a few years after the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans, a block of Little Tokyo businesses and residences was seized and demolished through eminent domain to make way for the Parker Center, the former headquarters of the Los Angeles Police Department. The Parker Center was in turn demolished in 2019, replaced by Toriumi Plaza, an open space above a parking garage, now owned by the Department of Transportation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, a community of unhoused residents formed at Toriumi Plaza, until they were forced out in a sweep in March 2022. All of this, of course, takes place on what was, for much longer than any subsequent settlement, Yaanga, the largest Tongva village.

Across the street from Toriumi Plaza is a building owned by my partner’s family since the early 1950s. His grandfather also owned a building very close to Silton’s in the Flower District. It’s now a parking lot. As I recounted all this, Silton looked down and found the stain that is featured alongside this writing.

Ana Iwataki is a writer, curator, and organizer from and based in Los Angeles. She is a PhD student in Comparative Studies in Literature and Culture at the University of Southern California. Her current research focuses on the cultural and spatial politics of Asian diaspora in gentrifying cities.

Susan Silton is based in Los Angeles. Her interdisciplinary projects engage multiple aesthetic strategies to mine the complexities of subjectivity and subject positions—often through poetic combinations of humor, discomfort, subterfuge and, beauty. Silton’s work takes the form of performative and participatory projects, photography, video, installation, and text/audio, and has been exhibited/presented nationally and internationally at MOCA, Los Angeles; SFMOMA, San Francisco; Luis De Jesus Gallery, Los Angeles; Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects; LAXART, Los Angeles; ICA/ Philadelphia; MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Los Angeles; and Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, among others.

Projects include the 2022 film/audio installation Bursting in air, Quartet for the End of Time (2017), the site-specific opera, A Sublime Madness in the Soul (2015), the multilayered book project Who’s in a Name? (2013), and the ongoing Whistling Project, which was included in SITE Santa Fe’s exhibition, 20 Years/20 Shows (2015). She has received fellowships and awards from the Getty/California Community Foundation, Art Matters, Cultural Affairs Department of the City of Los Angeles, Durfee Foundation, The Shifting Foundation, and Fellows of Contemporary Art (FOCA), among others. More recently, Silton was awarded an LA Metro commission for permanent installation in the Wilshire/Fairfax subway station. The first major traveling survey of Silton’s work, Diving into the Wreck will open at the Blaffer Museum in Houston in 2025, curated by art historian Andy Campbell.

- Susan Silton, in conversation with the author, January 2023. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Susan Silton, interviewed by Susanna Newbury, “Artists at Work: Susan Silton,” East of Borneo, July 15, 2019. ↩

- Susanna Newbury, ibid. ↩

- Silton, 2023. ↩

- Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 199. ↩

- Irit Rogoff, “Looking Away—Participations in Visual Culture,” in After Criticism—New Responses to Art and Perfomance, ed. Gavin Butt (Blackwell, 2005), 117–34. ↩

- Ibid., 126. ↩

- Silton. 2019. ↩

- Amelia Jones, Self/Image: Technology, Representation, and the Contemporary Subject (London: Routledg, 2006), 117–20. ↩

- Silton, Susan. Susan Silton: Self-Portraits (Cycle One, January–June, 1995) (Santa Monica, CA: Craig Krull Gallery, 1995). ↩

- Silton, 1995. ↩

- Rogoff, Irit, “We – Mutualities, Collectivities, Participations” in I Promise its Political (Museum Ludwig, Cologne, 2002). ↩

- Hannah Arendt, The Life of the Mind (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978), 50. ↩