I have always thought that artistic creation is a way for the skinless.

To provide oneself with skin.

—Kristina Lugn, “The Dog Moment”1

Skin is looming increasingly large across cultural studies and aesthetic theory, with scholars approaching this largest of biological organs from an array of sociocultural, psychoanalytical, and phenomenological perspectives.2 “Skin is in,” as Claudia Benthien’s succinct appraisal has it.3 Over the last three decades, artists have engaged skin as a risky boundary: an interface affording “inter-embodiment,” yet haunted by the risk of uninvited permeation.4 During the COVID-19 pandemic, borders have become sites of acute tension; the bodily borders of individual human beings are negotiated no less anxiously. Early twenty-first-century art experiments with skin in a striking variety of media—from animal hides to latex and silicone, from body painting to performance and bioart.5 Through these diverse approaches and practices, contemporary artists often relate to skin as both a site of dangerous exposure and a type of armor, assuming the form of a second skin. I explore mediations of skin in early twenty-first-century art, skin here being conceived as both a semantic trope and a concrete material presence.

Aesthetic experience intersects with somatosensory and cultural vectors. To grasp these conjunctures, my account couples a historical sense of how skin-related art addresses the condition of global mobility, entailing diasporicity and “skinlessness,” with a phenomenological reflection on skin’s haptic appeal. Along the phenomenological trajectory, I draw upon the growing discourse on haptic visuality and embodied aesthetics.6 Reviewing the growing body of empirical evidence indicating that sensorimotor information is involved in how people process artworks,7 Kendall Eskine and Aaron Kozbelt argue that “an embodied approach to an abstract domain like aesthetics should fruitfully inform our understanding of that domain.”8 Taking up these ideas, I adopt a somato-cultural approach that connects individual viewers’ somatosensory experiences with the sociocultural conditions under which skin emerges as a meaningful medium.9 Benthien has also sought to marry these concerns, stressing “the immense significance of skin as a symbolic form for cultural processes as a whole and its importance to the individuation and self-becoming of the human being, in particular.”10 Presupposing a synergy between these complementary historical and sensorial critical modes, I closely analyze a corpus of skin-related installations and videos. In and through these analyses, I show how skin signifies in an age in which mobility dissolves not only geopolitical borders but also subjective boundaries.

As Steven Connor compellingly suggests, “[p]erhaps the skin means, more than anything else in particular, the necessity for there to be a ground.”11 The concepts of skin-as-ground and skin-as-home resonate with the organ’s biological and psychological functions as a protective limit and enveloping shell. Naomi Segal has pointed out that “with a world running out of control, there is a need ‘to set limits.’”12 To illustrate this point, she describes how “[m]aths, biology, and neurophysiology have all become sciences of interfaces, membranes and borders.”13 Here I work with and through tropes of the skin as an identity marker, protective shell, and interface. Skins figure as productive means of engaging with borders and envelopes that are so tenuous they have to be fortified. Yet millennial skin-related art is not as politically explicit as some more outspoken migratory art projects.14 The installations to which I attend both subtly probe forms of insecurity that people feel in their own skin and query various Other skins. Heidi Kellett has postulated a “dialogic exchange between skins,” which she deems crucial to experiencing skin-based art.15 In this vein, I conclude by putting forward the phenomenological claim, supported by recent empirical studies, that skin-related art, at its best, might foster a “presence effect” that serves to reawaken viewers to their own skin envelopes and embodiment therein.16

The corpus under scrutiny clusters around three foci, which echo the skin’s symbolic functions in Didier Anzieu’s Skin-Ego theory (on which I will elaborate presently).17 Inevitable overlaps notwithstanding, the works are subsumed under the categories of double shells, skin fetishes, and destructured skins. I will discuss Nandipha Mntambo’s work with raw cowhides; Ana Álvarez-Errecalde’s synthetic skin-suits; Jessica Harrison’s imprinting of her own skin onto clay; the latex-clad protagonists of Wu Tien-chang’s videos; Pamela Rosenkranz’s work with the pink silicon known as Dragon Skin; Penny Siopis’s invocations of the South African horror figure Pinky Pinky in thickly laid oil paint; and Michel Platnic’s overpainting of faces and bodies in his video emulations of Francis Bacon and Egon Schiele.

Anzieu: The Skin-Ego, Double Shells, and Skin Fetishes

Didier Anzieu’s Skin-Ego theory has been recognized as a useful bridge between psychoanalytical and cultural concepts of skin.18 Here, I look particularly to Anzieu’s evocative use of skin myths, which provide a useful analytical framework within which to approach skin-related art. To situate these myths, a brief review of the Skin-Ego and its related set of concepts is in order. Anzieu’s psychoanalytical theory positions skin as “a primary datum which has elements of both the organic and the imaginary.”19 The Skin-Ego is thus conceived of as the interiorization of very early bodily and psychic sensations: of being shielded, contained, and physically supported by a caregiver within a shared skin-envelope.20 This concept is premised on Anzieu’s insistence that “every psychical function develops by leaning anaclitically on a bodily function, whose workings it transposes to the mental plane.”21 Like biological skin, the Skin-Ego thus fulfills the functions of a shield, barrier, containing envelope, and sensitive interface, “filtering exchanges (with the id, the superego and the outside world).”22 The Skin-Ego is formed on an interiorized supporting object, which provides a stable core for the fully individuated self.23

I follow Rikke Hansen and a range of other cultural critics in adopting Anzieu’s theory as a “suggestive starting point” for cultural analysis.24 Anzieu himself was the first to reach across received distinctions between the regimes of culture and biology by broaching the cultural dimensions of the Skin-Ego. While acknowledging the skin’s physiological role as an interface with reality, Anzieu asserted that skin also constitutes a primary cultural medium, as evidenced by social markings such as incisions, tattoos, makeup, and clothing.25

Connor has suggested extending Skin-Ego theory into the realm of the “cultural-poetic,” broadening the Skin-Ego’s containing function to account for the complexity and plurality of contemporary subjectivities.26 As Marc Lafrance has maintained, Anzieu’s relevance to cultural theory lies in how his theory demonstrates the crucial role of limits in forming human subjectivity, especially in relation to contemporary conditions of “fluidity, instability, and malleability.”27 It is for this reason that Anzieu’s emphasis on the centrality of skin—as both a cultural signifier and sensory medium—is at the heart of my argument.

According to Anzieu’s formulation, the Skin-Ego has nine functions.28 Of these, those of “containing” and “individuation” are most relevant to the present discussion.29 Recalling myths involving flaying—particularly the flaying of the satyr Marsyas for outshining Apollo in a musical contest—Anzieu outlines the universal fantasy of a mutual skin connecting baby and mother. The painful yet inescapable rift from the supportive body leaves the Self bereft of containment and support.30 Of particular interest here is the fantasy of the double wall, evoking “the protective wrapping, . . . which in phantasy one imagines taking from another person in order to . . . duplicate and strengthen one’s own.”31 For Anzieu, the flaying of Marsyas, despite its grotesqueness, bears redemptive potential. Although the containing and shielding skin becomes painfully detached from its grounding medium, it is “conserved whole and this ensures . . . the sustaining of life and the restoration of fertility.”32

Among the fundamental skin mythemes (narrative units of myths) that Anzieu highlights, the story of Zeus’s aegis or overgarment that was prepared from the skin of Amaltheia the nanny goat, pertains most directly to my discussion of doubled and fetishized skins. “The aegis not only makes a perfect shield in battle,” writes Anzieu, “but also augments Zeus’s powers, leading him to his unique destiny as the master of Olympus.”33 Another skin mytheme pertains to the river Marsyas gushing beneath the suspended skin of the offending satyr. Anzieu associates the river with “instinctual energy . . . available only to those who have preserved the integrity of their Skin-Ego.”34 A flayed yet vital skin figures centrally in these myths of recuperation.

In what follows, I look at a selection of installations that engage in anxious attempts to regrow epidermic envelopes and graft them onto injured Skin-Egos. I draw on Anzieu’s “fantasy of the double wall”35 and that of the “second muscular skin.”36 In Anzieu, the double wall is conceived as an imaginary defense ensuring the wholeness of the skin ego,37 whereas the second muscular skin indicates a “prosthetic substitute,” an objectified container countering internal fragmentation. I refer to the first as a double shell and the second as a skin fetish.

The double shells and skin fetishes addressed in the following section tap into a frightening sense of dissociation from the body. The idea of dissociation, which Anzieu finds in myths and fantasies of flaying, resonates in Franz Fanon’s concept of “epidermalization,”38 or the formation a “racial-epidermal schema”39 imposed by an objectifying, racist gaze. This construction of corporeal existence impairs the innate constitution of a bodily self. Fanon pictures detachment from the healthy, intuitive body schema as “an amputation, an excision,” through which one is “[s]ealed into . . . crushing objecthood.”40 Similarly, some installations to which I turn in the following sections render the skin a detached and objectified epidermal shell.

Skin as Home and Global Mobility

In focusing on the growing prominence of these epidermal shells in art installations, I bring the Skin-Ego to bear on contemporary art engaging with the dissolution of borders. In a cultural order pervaded by mobility, whether forced or voluntary, skin functions as a surface on which identity and belonging, body image and social standing are negotiated. Skin is and has been the quintessential focus of racism, discrimination, and persecution throughout history, and remains inscribed in contemporary culture as a crucial marker of Otherness.41

When approached in relation to art, though, there is more at stake in skin than individuals’ experience. Mieke Bal has proposed that “aesthetic encounter is migratory if it takes place in the space of, on the basis of, and on the interface with, the mobility of people as a given, as central, and as at the heart of what matters in the contemporary, that is, ‘globalized’ world.”42 For Bal, mobility is a pervasive sociocultural phenomenon, which is not limited to individual biographies. It is important that I stress this point at the very outset of my discussion, for it bears on the corpus that I examine. I do not limit my analysis to artists whose lives are marked by migration, or artworks that explicitly address the politics of migration. Rather, I concur with Murat Aydemir and Alex Rotas that the migratory participates in “formations and processes that may well, at first sight, seem untouched by migration.”43 Here, I am concerned with works that, instead of explicitly foregrounding mobility as their subject matter, relate to the idea of skin as home or ground, a sheltering envelope and an identity marker. Thus, the present discussion pivots not on the politics of migration, but rather on a sense of global turbulence that agitates our subjective and collective “shells.”

Sara Ahmed has subtly woven skin into her phenomenological description of “the lived experience of being-at-home.”44 I find her assertion, that migration involves “a spatial reconfiguration of an embodied self: a transformation in the very skin through which the body is embodied,” extremely helpful.45 Yet I seek to expand Ahmed’s focus beyond “the discomfort of inhabiting a migrant body.”46 Indeed, I stress the bidirectionality of this sociocultural malaise: On one side, emigrating subjects are haunted by a loss of home and ground. On the other, receiving communities are simultaneously deeply unsettled, as limits and borders become porous and permeable. Amid such contingencies, “human beings feel increasingly less sheltered in the skin,” Benthien asserts.47 Figuring global turbulence through the trope of the skin in contemporary art, then, speaks to the urgent need to seal and fortify failing envelopes while responding to intersubjective challenges.

Each of the artists whose works I address here is enmeshed and engaged with this global, though regionally differentiated, condition. The ways in which they approach it, however, unfold in relation to a range of different geographical and social contexts and are colored by their diverse backgrounds and experiences. Mntambo and Siopis work in South Africa across the racial gap. Born in Zimbabwe and growing up in postapartheid South Africa, Mntambo works from a Black African position;48 Siopis, the descendant of British and Dutch immigrants to South Africa, struggles to form a sense of belonging, ridden with guilt.49 Early on in the postapartheid era, Okwui Enwezor (a world-leading curator and theoretician of African art) accused Siopis and other white South African artists of recycling racist tropes rather than addressing the problematics of their own past.50 Driven to delve into her white identity in this way, Siopis’s engagement with racial anxiety is manifest in her series Pinky Pinky, which I later discuss.

Based like Siopis and Mntambo in a deeply troubled home country, Wu Tien-chang evokes Taiwan’s traumatic history of Chinese martial rule (1949–87). Coerced into adopting the Chinese language and culture,51 while at the same time inundated by American forces posted on the frontline with mainland communist China, Taiwan emerged from this period in a state of “diaspora at home.”52 Wu addresses identity-related tensions in his video installation Farewell, Spring and Autumn Pavilions (2015), discussed here.

Active in Barcelona, Spain, the Argentinian artist Álvarez-Errecalde remains within the cultural perimeter of the Spanish-speaking world.53 Her position perhaps best befits Anne Petersen’s description of contemporary itinerant artists as “transnational cultural worker[s].”54 Creating empty skin-suits tagged with the geographical and personal details of their original “wearers,” she posits a void at the center of identity. Harrison and Rosenkranz are based in Scotland and Switzerland, respectively. The geopolitical circumstances of these countries are not nearly as troubled as those of South Africa, Taiwan, or Argentina. Rosenkranz’s expressed aversion toward national identification, along with her ongoing uneasiness about Caucasian-tinted skin functioning as an identity marker,55 can be understood by way of Irit Rogoff’s concept of “active . . . unbelonging.”56 Although Rosenkranz is clearly apprehensive about the way in which skin can manifest ethnic Otherness, she has never openly addressed this point, which might bear on her biography. Finally, Platnic’s immigration from France to Israel is unique within the conceptual frame of migration, in that relocating to Israel from worldwide Jewish diasporas is conceived as a homecoming, albeit mingled with uprooting. While maintaining close cultural ties with his country of birth, Platnic has described his childhood as imbued with Otherness and insecurity.57 In Ahmed’s terms, he seems to have inherited “a body which feels out of place” from his Jewish parents.58 The son of a French-Jewish holocaust survivor, Platnic’s overpainting of his own skin bears the weight of personal and collective trauma.

Despite working across so many different situations and varied biographies, formal approaches, and concerns, each of these practitioners is experimenting with forms of epidermal covering or enclosure. Emerging from a mesh of mobilities—some current, others originating further back in history—these works tap into what I propose to read as an overwhelming sense of skinlessness in contemporary culture.

Double Shells, Second Skins

As a point of entry into my discussion of double shells, the first of skin’s symbolic functions I addressed in this essay, I turn now to the full-body skin-suits in Álvarez-Errecalde’s performative installation More Store (2009) and the accompanying photographic series Histologies (2011). In developing my analysis, I put Álvarez-Errecalde’s skin-suits in dialogue with Mntambo’s treated cowhides, which are sculpturally molded onto a cast of the artist’s body.

For More Store (2009), Álvarez-Errecalde created a series of life-size, stretchy skin-suits, based on photographs of forty anonymous nude women aged eighteen to seventy-five. Visitors to the installation may wear the suits, literally donning an Other’s skin. In a pseudocommercial gesture, which emphasizes the skins’ transformation into wearable objects, the artist sewed tags recording each woman’s age, spoken language, and nationality onto the suits.59 Addressing the “overwhelming desire to represent skin without a necessary connection to a body,” Kellett reads Álvarez-Errecalde’s work through the metaphor of skin-as-clothing.60 Kellett has coined a succinct term for work in this vein: haut [sic] couture, which puns on haut (skin) in German and the French haute couture (high fashion).61 The women’s skins, detached and objectified, tagged and displayed like fashion items, are patently invested in cultural critique. Yet there is no escaping the darker tones underlying this installation, which go beyond the artist’s stated concern with the “devitalization, domestication and exploitation” of female subjects in the global marketing system.62 Strikingly, the row of hanging skins resonates with slaughterhouse imagery, bringing a substratum of anxiety into view. Recall Anzieu’s fantasy of flayed skin functioning as a double shell: “the skin that has been torn from the body . . . represents the protective envelope, the shield, which one must take from the other in phantasy either simply to have it for oneself or to duplicate and reinforce one’s own skin.”63 The connotation of flaying is amplified in Álvarez-Errecalde’s subsequent, related photographic series Histologies (2011), in which female and male protagonists wrestle with the foreign skins, struggling uneasily to either fit them on or peel them off. Fitting in and out of the skin-suits requires a double effort: not only donning an ill-fitting garment but also taking on a body image that will inevitably be distorted due to age, gender, and ethnic differences between the suit and its wearer. Whereas visitors’ skin is actually stimulated in More Store, which involves putting the skin-suits on, stimulation is only suggested when one contemplates the photographs of Histologies. Álvarez-Errecalde is thus able to elicit somatosensory engagement, as if viewers are haptically feeling a vulnerable and often dysfunctional skin-envelope. In coming into uncomfortable proximity with “the ill-fitting ‘flayed’ skin of another,” participants become more aware of their own skin.64 Indeed, Álvarez-Errecalde’s skin-suits convey a deep vulnerability, hinting at a pending failure of the fantasy of the double shell.

Ana Álvarez Errecalde, More Store, 2009 (artwork © Ana Álvarez Errecalde; photograph provided by the artist)

Ana Álvarez Errecalde, More Store, 2009 (artwork © Ana Álvarez Errecalde; photograph provided by the artist)

Ana Álvarez Errecalde, from the series Histologies, 2011 (artwork © Ana Álvarez Errecalde; photograph provided by the artist)

Whereas Álvarez-Errecalde models synthetic skins on a global assortment of female bodies, Mntambo employs strange and unsettling animal/human taxidermy, molding raw cowhides onto casts of her own body. Addressing what she terms Mntambo’s “skin/ned politics,” Ruth Lipschitz espies a conjunction of postcolonial and feminist critique in the black-skinned human/animal hybrids.65 Mntambo herself has linked her choice of cowhide as a medium to the ongoing negotiation of identity in postapartheid South Africa.66 Problematizing implicit associations among woman, African, and animal, Mntambo’s taxidermy echoes the dissociation from the Othered body that Fanon described in Black Skin, White Masks. Beginning of the Empire (2007) features eleven furry black hides, shaped and chemically stiffened to take on the form of human female torsos.67 In Conversation: The Beginning of Forever (2015), white hides are fashioned into Victorian dresses, suggesting absent female bodies, the tails of the animals left intact in a disquieting instance of “human/animal hauntology.”68 The artist interferes with the hides’ physical memory of the living organism that once inhabited them: “as much as I try to control it through chemical processes or stretching it over a mould [sic], if I were to re-wet it, it would continue to remember a particular shape.”69 Two bodies, animal and human, thus inhabit a single shell. And while the artist struggles to mold it to her will, the hardened envelope harbors a treacherous memory of its nonhuman provenance, revealing “our fraught relationships with our hides,” in Kellett’s turn of phrase.70

These taxidermy-based installations exceed political critique, reaching a level of sensory intensity at which meaning emerges through the hide’s “abrasive materiality,”71 which recalls the “decay and rot and flies and maggots” involved in the working process.72 These unsettling animal/human shells might best be accounted for with Anzieu’s concept of the second muscular skin, which becomes “abnormally overdeveloped when it is brought in . . . to shore up the flaws, fissures and holes of the first containing skin.”73 Mntambo’s taxidermy, it seems, attempts to recuperate skin-envelopes that are no longer functional, to grow second muscular skins while exploring, as Hansen puts it, “the relationship between hides, hiding, and exposure.”74 Mntambo regards the “humps and bumps” of human morphology as signals of “safety, housing, a shield of some sort.”75 In replicating her own body curves in animal hides, then, the artist broaches concerns related to borders and shelter. Mntambo’s disturbing taxidermies involve a measure of aggression, which Anzieu sees as part of the defensive act of growing a second muscular skin.76 Through casting her own body, Mntambo vicariously inhabits the flayed yet vibrant skin shells.77 For Giovanni Aloi, the strength of these installations “lies in their irreducible essence as a surface layer peeled off from an animal.”78 But though Mntambo’s installations are inevitably aversive, they are also strangely enticing. Specifically, they appeal to our sense of touch. The excess that Lipschitz observes in these installations, then, works far beyond the critical “return of the abject.”79 A subject, stripped of integrity and safety, might fleetingly find relief in the sensory arousal afforded by the hardened and fetishized animal shells, which function as both double walls80 and second muscular skins,81 bridging the present discussion with what follows.

Nandipha Mntambo, Beginning of the Empire, 2007, installation view, Michaelis Gallery, Capetown (photograph provided by the artist)

Nandipha Mntambo, Conversation: The Beginning of Forever, 2015, installation view, 56th Venice Biennale (photograph provided by the artist)

Skin Fetishes: Latex Masks and “Skin-Furniture”

Connor views artificial skins as fetishes, reflecting “the fantasy of toughened skin . . . designed to produce a reassuring condition of impenetrability.”82 He particularly points to latex—among a variety of fetishized skins—as speaking to Anzieu’s fantasy of the double wall, which “appears to be the defensive counterpart to the phantasy of a fleshless skin.”83 Whereas Mntambo and Alvarez-Errecalde play out the fantasy of a fleshless skin, Wu Tien-chang’s pervasive use of latex masks speaks to the fetishizing drive.

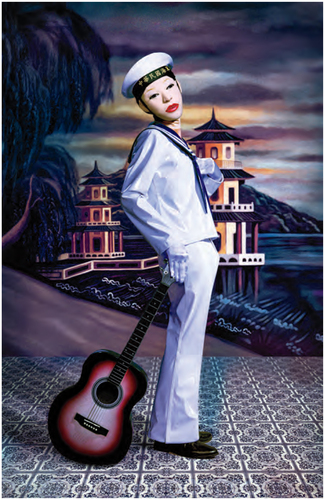

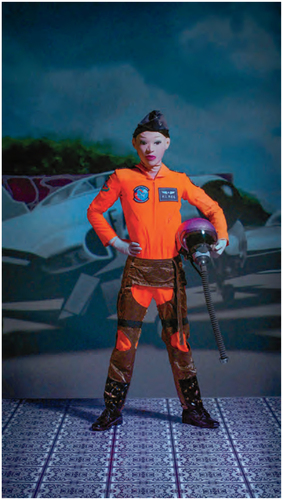

The single-channel video Farewell, Spring and Autumn Pavilions was presented in the Taiwan Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale. It features a tiny, claustrophobic stage with a painted backcloth depicting a Taiwanese landmark—the Spring and Autumn Pavilions. Although this background was popular in studio photography in the 1950s, Wu’s choice of this site is far from nostalgic. As he explained to me, the Spring and Autumn Pavilions are located in Zuoying, the administrative area of the Taiwanese naval base. Conscripted sailors often had their likenesses taken in photographic studios adjacent to the naval base; the photographers used the pavilions as a background to the portraits.84 A solitary figure, in a white sailor’s uniform, white gloves, and a full facial mask, poses onstage in a tableau vivant. As the sailor begins to march, his sprightly steps contrast starkly with the visible fact that he is marching on a conveyor belt and thus remaining in the same spot. The unsettling effect conjured by the expressionless mask is enhanced by the moving background. This latter technology recalls protocinematic contraptions such as the moving panorama.85 As the video proceeds, the sailor changes into a pilot’s overalls against the background of the Taoyuan Air Base, the seat of the secretive Black Cat Squadron, responsible for surveillance flights over Communist China during the Cold War. For the Taiwanese, the artist claims, the Black Cat Squadron represented the United States’ excessive military presence in their country, which profoundly shaped the experience of Wu’s generation.86 US sailors (“drunk and grabbing tight onto the hips of bar girls”) were a common sight in his native harbor city of Keelung; “the US army,” he says, “was my window on the world.”87

Wu Tien-chang, still from Farewell, Spring and Autumn Pavilions, 2015, installation view, Taiwan Pavilion, 56th Venice Biennale (artwork © Wu Tien-chang; image provided by the artist and Tina Keng Gallery, Taipei)

Wu Tien-chang, still from Farewell, Spring and Autumn Pavilions, 2015, installation view, Taiwan Pavilion, 56th Venice Biennale (artwork © Wu Tien-chang; image provided by the artist and Tina Keng Gallery, Taipei)

Thus, when the video ends and the screen darkens, a life-size ghost sailor materializes as if floating in midair. Emerging from a troubled past, this strange apparition is created by yet another nineteenth-century stage trick, the Pepper’s Ghost Illusion.88 The artist has chosen to negotiate the trauma of colonized Taiwan, it would seem, by way of nineteenth-century apparatuses of “virtual reality” such as the moving panorama and mirror illusions. In this way, he invokes the ghosts of the past while maintaining a safe distance.

When I asked him directly about his use of latex as surrogate skin, Wu responded by invoking the notion of fetish, “a form of self-healing through retrospection and licking one’s wounds from the early days. . . . Just like many toddlers . . . substitute mothers’ skin with stuffed animals or security blankets.”89 Thus, Farewell, Spring and Autumn Pavilions manifests an excessive materiality that recalls Anzieu’s concept of “hypercathecting the narcissistic skin.”90 The plastic uniforms’ sheen and bright colors are crucial in this respect, as are the velvet curtain and colored lights flanking the video monitor. The white latex mask—a layer of detached and objectified skin, eerily recalling Fanon’s titular White Masks—is especially important. The eerie impression of dissociated skin derives particularly from the areas around the eye sockets, which constitute the sole trace of human expression in an otherwise frozen look. Like dead skin, the rubber mask is not wired for sensation. Given its lack of muscular agency, the mask thwarts intersubjective communication, leaving the protagonists isolated within a fetishized skin that is communicatively dysfunctional yet protective.

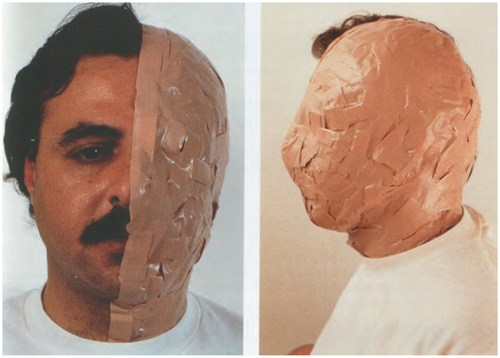

A useful analogy can be drawn between Wu’s surrogate facial skin and Palestinian artist Khalil Rabah’s series Half-Self-Portraits (1997). Gannit Ankori analyzed this series in terms of a “split Self,” held together by adhesive Band-Aids. Drawing on Fanon, Ankori notes the contrast between the Band-Aids’ normalized Caucasian pinkish color and the artist’s dark skin. Further, Ankori highlights another tension that the Band-Aid skin foregrounds: that between schism and suture.91 The latex skins of Wu’s figures enact a similar splitting of the Self, whereby the fetishized encasing latex functions as an “ego-reinforcing compromise between the ego and that which threatens to lacerate or destroy its fragile self-enclosure.”92

In another vein, Harrison’s viscerally troubling series Handheld (2009) resonates with Anzieu’s notion of fetishized skin. Here, the artist imprints her own epidermal texture onto clay, which she forms into minuscule furniture. Disturbingly, these objects seem to be upholstered using human skin. This unsettling impression is augmented by visible creases, wrinkles, and even hairs. As with Mntambo’s and Wu Tien-chang’s works, Harrison’s fetishization of skin is at once successful and abortive. The artist presents the skin-furniture in photographic compositions, held in the palm of her hand. In so doing, the artist multiplies and hardens her own epidermis, so that it seemingly hovers between living and dead matter. Harrison’s furniture has a striking anthropomorphic quality; at the same time, the artist’s own hand becomes a decontextualized object, as Kellett has noted.93 In the absence of a face, the artist’s hand is no less an object than the “skinned” furniture it holds. This ontological ambiguity is responsible for the unnerving air of Harrison’s skin fetishes. Invoking the horror of flaying in conjunction with commodity consumption, thus coming dangerously close to cannibalism, the Handheld series is deeply disturbing. Unlike Wu’s latex masks, which emulate the human face but retain a sleek, inorganic texture, Harrison forfeits human morphology and accentuates epidermal texture until it becomes a “dermography,” to use Ahmed and Stacey’s evocative coinage.94

Khalil Rabah, Half-Self-Portrait, 1997 (artwork © Khalil Rabah; photograph provided by the artist)

Jessica Harrison, Armchair, 2009, from the series Handheld (artwork © Jessica Harrison; photograph provided by the artist)

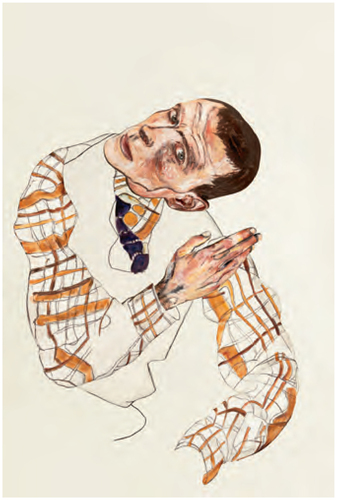

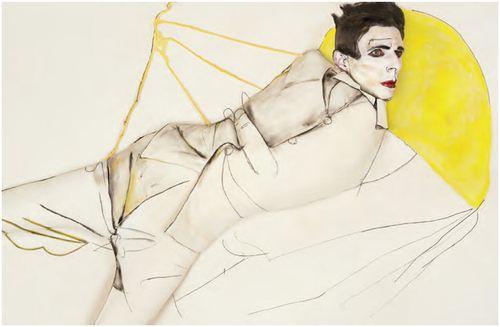

My discussion of skin fetishes and the fantasy of hardened skin concludes with works by Michel Platnic. Some of Platnic’s early experiments involved overpainting his own face and torso, directly engaging with his skin as both a sensate and symbolic surface. Yet Platnic did not stop at “hypercathecting” the skin through paint’s excessive materiality.95 His series After Bacon (2014) and, more recently, Bordermine (2020) explore intermedial crossings. Again, they feature the artist with his body painted over, but this time in video tableaux emulating paintings by Bacon and Schiele, respectively. After Bacon (2014) comprises performative video reconstructions of Bacon’s triptychs. Platnic constructed compelling three-dimensional emulations of Bacon’s distorted spaces, within whose claustrophobic confines he and other performers move. Emphasizing rather than downplaying the dissonance between painting and moving images, Platnic plays depth against surface and motion against stillness, while bringing paint to bear on flesh. In conversation with me, he associated the Bacon series with Jean-Paul Sartre’s play No Exit, written in occupied Paris in 1944.96 Considering that Platnic’s father survived the Nazi occupation of France as a young child in hiding, the works’ sense of claustrophobic confinement is doubtlessly autobiographical—to evoke Bacon’s postwar art at all is to stir anxiety. Yet by casting himself as Bacon’s protagonists and assuming their skinlessness, Platnic is partially able to reembody Bacon’s flayed figures.97 Gilles Deleuze highlighted the “pictorial tension between flesh and bone” in Bacon’s paintings;[98Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon, The Logic of Sensation (London and New York: Continuum, 2003), 22. First published 1981.] Platnic, in turn, harnesses skills that he acquired during his earlier career in engineering to reconstruct Bacon’s skewed skeletal structures, and endow “with faces” the flayed figures within, thereby retrieving their lost humanity.

Michel Platnic, Self-Portrait, 2009 (artwork © Michel Platnic; photograph provided by the artist)

Michel Platnic, After Three Studies of Lucian Freud, 1969,” 2014 (artwork © Michel Platnic; photograph provided by the artist)

Michel Platnic, Self-Portrait with Checkered Blouse: After Self-Portrait with Checkered Shirt, 2020 (artwork © Michel Platnic; photograph provided by the artist)

Michel Platnic, Boy Lying Down: After “Reclining Boy (Erich Lederer),” 2020 (artwork © Michel Platnic; photograph provided by the artist)

In Bordermine (2020), Platnic impersonates Schiele’s self-portraits in visually haunting and technically ambitious videos and stills. The artist’s face is fully painted in emulation of Schiele’s self-portraits. At the same time, parts of his body seem paper-thin, having been squeezed into specially designed, tight-fitting straitjackets. The series’ very title, Bordermine, complicates notions of selfhood and identity, with Platnic seeking to define his borders within another artist’s self-portrait. With more than a hint of apprehension, his practice interrogates the skin’s function as a self-defining boundary, a “bordermine.” The art historical reference to Schiele is no less telling. Gerald Izenberg’s psychohistorical account of Schiele’s conflicted self-portraits highlights their “fragmentation without any coherent sense of self at all.”98 On this basis, Izenberg interprets Schiele’s ubiquitous use of mirrors as an inversion of the Lacanian mirror stage, through which the ego forms. In Schiele, he writes, “the opposite seems to happen: the illusory upright ego is deconstructed into its fragments.”99

Platnic is not the first artist to respond to Schiele’s self-portraits and disturbing female nudes. In 1995, the performance artist John Kelly presented the performance Pass the Blutwurst, Bitte, in which he impersonated Schiele’s appearance using makeup. Enacting intricately choreographed motions that resonated with the contorted postures of the bodies that figure in Schiele’s paintings and drawings, Kelly staged compelling vignettes from the Viennese artist’s tragically short life.100 The Italian dancer Claudia Contin Arlecchino has also responded to Schiele’s signature body language. Under the title of tragedia dell’arte, she developed a vocabulary of choreographic gestures based on Schiele’s figures.101 Whereas these projects respond to Schiele’s anguished motions and postures, Platnic seems more occupied with the tension between body volume and surface. As he incorporates himself into Schiele’s drawings, he becomes disembodied. Trading body volume for the flatness of paper, Platnic becomes a fleshless skin. At one level, his practice of growing a second skin of painting—consisting of important specimens from the canon of modern art—recalls Anzieu’s fetishized or objectified second skin. At another, Platnic’s particular choice of painters (Bacon and Schiele) speaks of vulnerability and very thin skin, with After Bacon suggesting skinless flesh and Bordermine invoking the fantasy of flaying, implying a thin, fleshless skin.

Destructured Skins

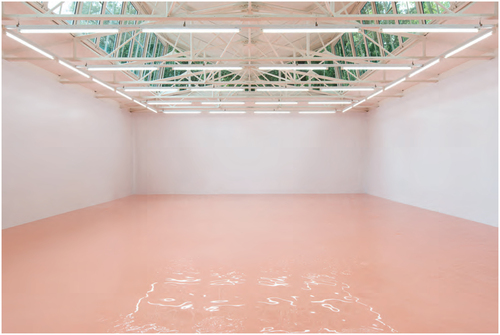

I conclude with works by Rosenkranz and Siopis in which wrappings or containers completely dissolve. In Our Product (2015), Rosenkranz transformed the Swiss Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale into a huge pool filled with a pinkish liquid. According to the exhibition statement, the pink liquid was of “a standardized northern European skin-tone” and combined several ingredients, Evian water and silicone among them.102 The multisensory effect that the artist intended for the installation was enhanced by a synthesized scent “evoking the smell of fresh baby skin.”103

Rosenkranz’s oeuvre manifests an ongoing concern with skin and Self, which she presents as products of a globalized capitalist culture in which “products are increasingly branded as if they were subjects.”104 In an earlier series, Firm Being (2009–11), she employed a liquid silicon product known as Dragon Skin, which is used in the film industry to create flesh-colored masks. In Firm Being, bottles produced by international mineral-water brands such as Evian, Fiji, and San Benedetto—all evoking pristine, unspoiled nature—were filled with pink-tinted Dragon Skin. The pigmented liquid refers to globalized identity constructs, materializing in “the very flesh colors of predominant Evian target groups.”105

Uneasiness creeps into Rosenkranz’s Venice installation, not least given the sheer quantity of liquid solution that has been tinted to evoke the color of northern European skin.106 Taken as a metaphor for the Skin-Ego, the pool of pink silicon appears to stage the diffusion and dissemination of a Self no longer held within firm boundaries, whether those be social, cultural, or historical. Whereas Firm Being’s branded plastic bottles still function as humanoid envelopes, albeit commodified, in Our Product the liquid spills out in an unformed cascade of destructured skin. And yet, the installation assumes the presence of fully embodied and sensually agile agents, addressed via compelling visual, auditory, and olfactory stimulations. Effectuating what Bal calls “sentient binding,” Rosenkranz thus destructures skin as a cultural construct only to reconstruct it as a sensate, embodied presence.107

If Platnic grafts replacement skin onto the raw flesh of Bacon’s figures, Siopis evokes Bacon to undergird her project of “pulling the form . . . away from the subject, [dragging] form and figuration to the verge of formlessness.”108 Her series of paintings Pinky Pinky (2002–5) centers around a South African horror figure, which the artist has described as neither Black nor white, an undefined “half-man, half-woman, half-human, half-creature.”109 The Pinky Pinky paintings are made up of thickly laid pink oil paint. This “host of pinkness” congeals into suggestive yet featureless faces, in which fake teeth, eyelashes, toenails, and plastic wounds are embedded.110

Conceiving of the Pinky Pinky paintings, in a Deleuzian sense, as “carnal document[s],”111 Siopis has invested them with the formlessness and excessive material intensity of what Deleuze and Félix Guattari called a “Body without Organs.”112 As in Rosenkranz’s silicon installations, Siopis’s skins fail to fulfill their containing function, exposing flesh in all its extremely problematic pinkness. The evocative texture of fleshy paint renders the horror of the Pinky Pinkys palpably and viscerally present. Unlike the sense of liberation that attends Deleuze and Guattari’s Body without Organs, here the images of destructured skin are suffused with unrelievable anxiety.

Coda: Art for the Skinless

Contemplating Anzieu’s relevance “for our time,” Andrzej Werbart has lingered over the dual need to find ways of “restoring boundaries and promoting exchanges across borders.”113 Whereas Werbart’s perspective is first and foremost psychoanalytic, one might well contend that bodily and geographical boundaries are also becoming sites of individual and collective insecurity. The COVID-19 pandemic has overwhelmingly reinforced this condition, to which the artists discussed here seem to have responded with compelling skin-related experiments. In these works, damaged skin envelopes and fetishized double shells are brought to bear on inhabited bodies no less than on society and politics. As a concluding proposition, I want to consider the possibility that there might be something consoling about skin-related art, which goes beyond anxieties around porous borders.

What I am proposing is that such works might augment viewers’ awareness of their own bodily borders, if only for the duration of the gallery visit. I would describe this as a sense of being encased in a body in space, which I associate with Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht’s “presence effect.”114 In a line that bears on the conjunction of skin, home, and art, the experimental filmmaker Phil Solomon told me that “artists are often familiar with never quite feeling at home in the world or even in your own skin . . . hence we create new worlds and new skins in the privacy of the creative act.”115 This suggestion dovetails with the poem “The Dog Moment” by Kristina Lugn, speculating on art as a recuperative “way for the skinless.”116 With these thoughts in mind, it is worth investigating the apparatus that affords potential aesthetic relief to skinless subjects of this troubled age.

The popular notion of “touching with the eyes,” which Laura Marks conceptualizes as “haptic visuality,” is crucial to understanding how art might augment one’s feeling of inhabiting an enclosed physical body.117 In the following remarks, I bring important phenomenological postulations proffered by Marks, Vivian Sobchack, Bernadette Wegenstein, and Kellett into conjunction with studies in cognitive neuroscience that suggest an intriguing approach to skin-related art.118 To my knowledge, the somatosensory processing of artworks’ visual textures, and these textures’ effect on viewers’ skin sensations, have not been investigated empirically.119 Related studies, albeit not focused on art, may be helpful. An fMRI study conducted by Hua-Chun Sun and her coauthors, for example, shows that observing and processing visually represented texture (i.e., texture that is presented visually while not being physically there) involves a cross-modal, visual-somatosensory network in the brain’s cortex.120 This study was even able to distinguish between somatosensory patterns that were activated by rough and smooth visual textures. The authors hypothesize that “if the brain has a system to generate expectations of tactile sensations when looking at objects with distinctive surface properties, changes in appearances that affect such expectations should elicit different activation responses in somatosensory cortex.”121 Based on their results, the authors explain that somatosensory cortices’ responses to visual textures are predicated upon the potential outcome of engaging with these textures. Interestingly, Sun and her colleagues found particularly pronounced responses to visual roughness in a cortical somatosensory region that earlier studies have shown to be active during actual physical stimulation by rough surfaces.122 This means that visually observing rough textures involves what Antonio Damasio has called “as-if body loops,” whereby the brain simulates physical sensation—in this case, tactile contact with a visually rendered texture.123 Also notable is a study by Simon Lacey, Randall Stilla, and Krish Sathian, showing that texturally suggestive idioms (such as “a rough day”) activated somatosensory brain areas, unlike semantically similar control sentences that lacked textural suggestion (such as “a bad day”).124 In a similar vein, India Morrison and her coauthors proposed that sensory expectation underlies somatosensory responses to images of noxious objects (a broken wine glass, for example), as opposed to harmless objects (such as an unbroken glass).125 This study highlighted brain regions that were sensitive to the target object’s tactile properties. On the basis on these studies, read in conjunction with phenomenological theories of haptic aesthetics, I would like to raise the possibility that skin-related art is particularly well-suited to arousing sensory expectations. Mntambo’s hairy hides, Harrison’s “dermographies,” Wu’s inorganically smooth latex masks, Platnic’s painted skin, Siopis’s amassed paint, and Rosenkranz’s liquid silicon are strong candidates for inducing this type of somatosensory arousal.

Here, I respond to Gumbrecht’s call for “new, presence-based ways of thinking aesthetics.”126 In Gumbrecht’s terms, this implies a bottom-up processing of sensory inputs, activating “a layer in our existence that simply wants the things of the world close to our skin.”127 It may be that the heightened somatosensory arousal that I have postulated here fosters a consoling presence effect—Lugn gestures towards this in designating art a “skin for the skinless.” In the works I have discussed, skin performs as a site of somato-cultural interrogation, where skin-related anxieties are probed and a consoling, if fleeting, sense of presence is afforded.

Hava Aldouby is senior lecturer in The Open University of Israel’s Department of Literature, Language, and the Arts, and artistic director of the Open University Gallery. Her research focuses on phenomenological aspects of the interface between contemporary art, global mobility, and peripheral identities, with an emphasis on surfaces, textures, and skins. Her monograph The European Canon and Contemporary Artists’ Moving Image is forthcoming from Palgrave Macmillan.

- Quoted and translated from Swedish in Andrzej Werbart, “‘The Skin is the Cradle of the Soul’: Didier Anzieu on the Skin-Ego, Boundaries, and Boundlessness,” Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 67, no. 1 (2019): 38. ↩

- See Sara Ahmed and Jackie Stacey, eds., Thinking through the Skin: Transformations (New York: Routledge, 1999); Didier Anzieu, The Skin-Ego, trans. Naomi Segal (London: Karnac Books, 2016); Claudia Bethien, Skin: On the Cultural Border between Self and World, trans. Thomas Dunlap (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002); Austin Booth and Mary Flanagan, Re:skin (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006); Anne Anlin Cheng, Second Skin: Josephine Baker and the Modern Surface (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013); Steven Connor, The Book of Skin (London: Reaktion Books, 2004); Michelle Stephens, Skin Acts: Race, Psychoanalysis and the Black Male Performer (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014); Dirk Vanderbeke and Caroline Rosenthal, Probing the Skin: Cultural Representations of Our Contact Zone (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015); Bernadette Wegenstein, Getting under the Skin: Body and Media Theory (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006); and Werbart, “‘Skin is the Cradle.’” ↩

- Bethien, Skin, 2. ↩

- Ahmed and Stacey, Thinking through the Skin, 4. ↩

- For skin-related bioart, which is not discussed in this essay, see the Tissue Culture and Art Project. ↩

- See Laura Marks, Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002) for a discussion of haptic visuality. In writing on embodied aesthetics, I have drawn on the following texts: Vivian Sobchack, Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004); David Freedberg and Vittorio Gallese, “Motion, Emotion and Empathy in Esthetic Experience,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11, no. 5 (2007): 197–203; and Cinzia Di Dio and Vittorio Gallese, “Neuroaesthetics: A Review,” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 19, no. 6 (2009): 682–87. See also Hava Aldouby, Béatrice Hasler, Tehila Nadav, and Doron Friedman, “Viewing Images of Jagged Texture in Digital Artwork Affects Body Sensations: A Virtual Reality Study,” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 2022, advance online publication. ↩

- Kendall J. Eskine and Aaron Kozbelt, “Art That Moves: Exploring the Embodied Basis of Art Representation, Production, and Evaluation,” in Aesthetics and the Embodied Mind: Beyond Art Theory and the Cartesian Mind-Body Dichotomy, ed. Alfonsina Scarinzi (Heidelberg: Springer, 2015), 157–73. ↩

- Ibid., 163. ↩

- Embodied aesthetic experience has attracted increasing research interest over recent decades. See Freedberg and Gallese, “Esthetic Experience”; Marta Calbi, Hava Aldouby, Ori Gersht, Nunzio Langiulli, Vittorio Gallese, and Maria Alessandra Umiltà, “Haptic Aesthetics and Bodily Properties of Ori Gersht’s Digital Art: A Behavioral and Eye-Tracking Study,” Frontiers in Psychology 10, no. 2520 (2019), https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02520/full; and M. Alessandra Umiltà, Cristina Berchio, Mariateresa Sestito, David Freedberg, and Vittorio Gallese, “Abstract Art and Cortical Motor Activation: An EEG Study,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 6, no. 311 (2012). ↩

- Benthien, Skin, 6. ↩

- Connor, Book of Skin, 38. ↩

- Naomi Segal, Consensuality: Didier Anzieu, Gender, and the Sense of Touch (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2009), 44. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Examples include Ai Weiwei’s Good Fences Make Good Neighbors (2017), which focused on border regulation and the movement of people, and Tiffany Chung’s Unwanted Population (2017), which traced African migration routes to Europe. ↩

- Heidi Kellett, “Skin Portraiture: Relational Embodiment and Contemporary Art,” in Vanderbeke and Rosenthal, Probing the Skin, 249. ↩

- Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, Production of Presence: What Meaning Cannot Convey (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004). ↩

- Anzieu, Skin-Ego. ↩

- Marc Lafrance, “From the Skin Ego to the Psychic Envelope: An Introduction to the Work of Didier Anzieu” in Skin, Culture and Psychoanalysis, ed. Sheila L. Cavanagh, Angela Failler, and Rachel Alpha Johnston Hurst (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 16–44; Segal, Consensuality, 2009; and Valerie Walkerdine, “Communal Beingness and Affect: An Exploration of Trauma in an Ex-industrial Community,” Body and Society 16, no. 1 (2012): 91–116. ↩

- Anzieu, Skin-Ego, 3. ↩

- Ibid., 43–44. ↩

- Ibid., 103. ↩

- Ibid., 44. ↩

- Ibid., 21. ↩

- Rikke Hansen, “Animal Skins in Contemporary Art,” Journal of Visual Art Practice 9, no. 1 (2002): 10. See also Segal, Consensuality; Connor, Book of Skin; and Walkerdine, “Communal Beingness.” ↩

- Anzieu, Skin-Ego, 114. ↩

- Connor, Book of Skin, 91. ↩

- Lafrance, “Psychic Envelope,” 20. ↩

- Anzieu, Skin-Ego, 98. ↩

- Ibid., 101–3. ↩

- Ibid., 44–48. ↩

- Ibid., 54. ↩

- Ibid., 51. ↩

- Ibid., 54. ↩

- Ibid., 55. ↩

- Ibid., 141. ↩

- Ibid., 217. ↩

- Ibid., 141 ↩

- David Marriott, “Waiting to Fall,” CR: The New Centennial Review 13, no. 3 (2013): 168. ↩

- Franz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (London: Paladin, 1970), 111. See also David Marriott, Whither Fanon: Studies in the Blackness of Being (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018); and Michelle Stephens, “Skin, Stain and Lamella: Fanon, Lacan, and Inter-racializing the Gaze” Psychoanalysis, Culture and Society 23, no. 3 (2018): 310–29. ↩

- Fanon, Black Skin, 109. ↩

- See, among others, Sara Ahmed, “Home and Away: Narratives of Migration and Estrangement,” International Journal of Cultural Studies 2, no. 3 (2001): 329–47; Karen Brodkin, How Jews Became White Folks and What That Says About Race in America (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1998); Cheng, Second Skin; Cedric Herring, Verna M. Keith, and Hayward Derrick Horton, eds., Skin Deep: How Race and Complexion Matter in the “Color-Blind” Era (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004); Margaret Hunter, “The Persistent Problem of Colorism: Skin Tone, Status, and Inequality,” Sociology Compass 1, no. 1 (2007): 237–54; and Joanne L. Rondilla and Paul Spickard, Is Lighter Better? Skin-Tone Discrimination among Asian Americans (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007). ↩

- Mieke Bal, “Lost in Space, Lost in the Library,” in Essays in Migratory Aesthetics: Cultural Practices between Migration and Art-Making, ed. Sam Durrant and Catherine M. Lord (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2007), 23–24. ↩

- Murat Aydemir and Alex Rotas, “Introduction: Migratory Settings,” in Migratory Settings, ed. Aydemir and Rotas (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 2008), 9. ↩

- Ahmed, “Home and Away,” 341. ↩

- Ibid., 342. ↩

- Ibid., 343. ↩

- Benthien, Skin, 237. ↩

- Hansi Momodu-Gordon, 9 Weeks (Cape Town: Stevenson Gallery, 2016), 119. ↩

- Allison K. Young, “‘We Never Did Return’: Migration, Materiality and Time in Penny Siopis’ Post-Apartheid Art,” Contemporaneity: Historical Presence in Visual Culture 4, no. 1 (2015): 49. ↩

- Ibid., 54. ↩

- Joan Lebold Cohen, “Art and Politics in China and Taiwan: Ai Weiwei and Wu Tien-chang,” Modern China Studies 18, no. 2 (2011): 83–99. ↩

- Christopher Lupke, “Fractured Identities and Refracted Images: The Neither/Nor of National Imagination in Contemporary Taiwan,” positions 17, no. 2 (2009): 247. ↩

- See Ana Álvarez-Errecalde’s official website. ↩

- Anne Ring Petersen, “The Locations of Memory: Migration and Transnational Cultural Memory as Challenges for Art History,” Crossings: Journal of Migration and Culture 4, no. 2 (2013): 121. ↩

- Pamela Rosenkranz, “Artistic Bacteriology: Pamela Rosenkranz,” interview by Nicolas Bourriaud, L’Officiel, June 1, 2015. ↩

- Irit Rogoff, Terra Infirma: Geography’s Visual Culture (London: Routledge, 2000), 5. ↩

- Michel Platnic, personal communication with the author, August 2020. ↩

- Ahmed, “Home and Away,” 343. ↩

- Kellett, “Skin Portraiture,” 261. ↩

- Ibid., 243. ↩

- Ibid., 258. ↩

- “More Store,” Ana Álvarez-Errecalde ↩

- Anzieu, Skin-Ego, 50. ↩

- Ibid., 264. ↩

- Ruth Lipschitz, “Skin/ned Politics: Species Discourse and the Limits of ‘The Human’ in Nandipha Mntambo’s Art,” Hypatia 27, no. 3 (2012): 546–66. ↩

- Momodu-Gordon, 9 Weeks, 119. ↩

- On cultural linkages among women, animals, and Africans, see Giovanni Aloi, Speculative Taxidermy: Natural History, Animal Surfaces, and Art in the Anthropocene (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), loc. 4187 of 7820, Kindle. ↩

- Ibid., loc. 4123 of 7820, Kindle. ↩

- Nandipha Mntambo, quoted in Momodu-Gordon, 9 Weeks, 127. ↩

- Kellett, “Skin Portraiture,” 266. ↩

- Aloi, Speculative Taxidermy, loc. 373 of 7820, Kindle. ↩

- Momodu-Gordon, 9 Weeks, 119. ↩

- Anzieu, Skin-Ego, 219. ↩

- Hansen, “Animal Skins in Contemporary Art,” 12. ↩

- Momodu-Gordon, 9 Weeks, 129. ↩

- Anzieu, Skin-Ego, 220. ↩

- Aloi, Speculative Taxidermy, loc. 475 of 7820, Kindle. ↩

- Ibid., loc. 4162 of 7820, Kindle. ↩

- Lipschitz, “Skin/ned Politics,” 555. ↩

- Anzieu, Skin-Ego, 141 ↩

- Ibid., 217. ↩

- Connor, Book of Skin, 53. ↩

- Anzieu, Skin-Ego, 141. ↩

- Wu Tien-chang, email to the author, March 30, 2016. ↩

- Erkki Huhtamo, “Global Glimpses for Local Realities: The Moving Panorama, a Forgotten Mass Medium of the 19th Century,” Art Inquiry: Recherches sur les Arts 4 (2002): 193–228. ↩

- Wu Tien-chang, email to the author, March 30, 2016. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- The Pepper’s Ghost Illusion is a stage trick known since the 1860s. A semitransparent mirror is placed at an angle to the stage and the audience, allowing full view of the stage while reflecting an offstage figure. The audience is only able to see the ghostly reflection of the offstage figure, against the fully realistic view of the stage. Thus, a “ghost” appears onstage. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Anzieu, Skin-Ego, 141. ↩

- Gannit Ankori, “‘Dis-Orientalisms’—Displaced Bodies/Embodied Displacements in Contemporary Palestinian Art,” in Uprootings/Regroundings: Questions of Home and Migration, ed. Sara Ahmed, Claudia Castañeda, Anne-Marie Fortier, and Mimi Sheller (Oxford, UK: Berg, 2003), 79–80. ↩

- Connor, Book of Skin, 49–50. ↩

- Kellett, “Skin Portraiture,” 254–55. ↩

- Ahmed and Stacey, Thinking through the Skin, 1. ↩

- Anzieu, Skin-Ego, 141. ↩

- Michel Platnic, personal communication with the author, August 2019. ↩

- As if seeking to render Bacon’s skinless subjects present to viewers, Platnic repeatedly emphasizes that everything in the video is physically real and is not the result of digital manipulation. ↩

- Gerald Izenberg, “Egon Schiele: Expressionist Art and Masculine Crisis,” Psychoanalytic Inquiry 26, no. 3 (2006): 467. ↩

- Ibid., 471. ↩

- John Kelly, director, “Pass the Blutwurst, Bitte (complete performance),” May 4, 2012, 1:23:32. ↩

- Giulia Vittori, “Choreographing Expressionist Paintings: Claudia Contin Arlecchino Dances Egon Schiele,” Dance Chronicle 41, no. 2 (2018): 212–38. ↩

- Enrico, “Pamela Rosenkranz: Our Product. Swiss Pavilion at Venice Art Biennale 2015,” Vernissage TV, May 14, 2015. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Susanne Pfeffer, “Our Product” (curator’s statement), from “Pamela Rosenkranz Fills Swiss Pavilion with Immaterial Elements at Venice Biennale 2015,” Design Boom, May 8, 2015. ↩

- Katya García-Antón, Gianni Jetzer, and Hilke Wagner, introduction to Pamela Rosenkranz: No Core (Zurich: JRP/Ringier, 2012), 16. ↩

- Enrico, “Pamela Rosenkranz: Our Product. ↩

- Bal, “Lost in Space.” ↩

- Sarah Nuttall, “An Unrecoverable Strangeness: Some Reflections on Selfhood and Otherness in South African Art,” Critical Arts 24, no. 3 (2010): 463. ↩

- Sarah Nuttall, “Wound, Surface, Skin,” Cultural Studies 27, no. 3 (2013): 430. ↩

- Sarah Nuttall, “Penny Siopis’s Scripted Bodies and the Limits of Alterity,” Social Dynamics 37, no. 2 (June 2011): 290. ↩

- Quoted in Nuttall, “Penny Siopis’s Scripted Bodies,” 297. ↩

- Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 153. ↩

- Werbart, “‘Skin is the Cradle,’” 56. ↩

- Gumbrecht, Production of Presence, 106. ↩

- Hava Aldouby, “An Outsider in Grand Theft Auto: Phil Solomon,” Art Journal 80, no. 2 (2020): 85. ↩

- Quoted in Werbart, “‘Skin is the Cradle,’” 38. ↩

- Marks, Touch. ↩

- Marks, Touch; Sobchack, Carnal Thoughts; Wegenstein, Getting under the Skin; and Kellett, “Skin Portraiture.” ↩

- See Aldouby, Hasler, Nadav, and Friedman, “Viewing Images of Jagged Texture in Digital Artwork Affects Body Sensations.” ↩

- Hua-Chun Sun, Andrew E. Welchman, Dorita H. F. Chang, and Massimiliano Di Luca, “Look but Don’t Touch: Visual Cues to Surface Structure Drive Somatosensory Cortex,” NeuroImage 128 (2016): 353–61. ↩

- Ibid., 354. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Antonio R. Damasio, Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain (New York: Pantheon Books, 2010). ↩

- Simon Lacey, Randall Stilla, and Krish Sathian, “Metaphorically Feeling: Comprehending Textural Metaphors Activates Somatosensory Cortex,” Brain and Language 120, no. 3 (2012): 416–21. ↩

- India Morrison, Steve P. Tipper, Wendy L. Fenton-Adams, and Patrick Bach, “Feeling” Others’ Painful Actions: The Sensorimotor Integration of Pain and Action Information,” Human Brain Mapping 34 (2013): 1982–98. ↩

- Gumbrecht, Production of Presence, 20. ↩

- Ibid., 106. ↩