This article first appeared in Art Journal vol. 83, no. 3 (Fall 2024)

DRC No. 12 is an independent nonprofit art space in Beijing housed within a two-bedroom apartment within the Diplomatic Residence Compound, which is often abbreviated to DRC. Located on Jianguomenwai Avenue in the Chaoyang District, DRC was established in 1971 as the first office and residence compound in the People’s Republic of China for foreign staff of embassies, international organizations, and news agencies. During the 1970s and 1980s, DRC became a cradle of cross-cultural exchanges and avant-garde art practices which attracted many artists, filmmakers, rock musicians, and writers to the compound. Although it is not quite an area of extraterritoriality, DRC has created an alternative diplomatic domain partially outside the control and surveillance of Chinese authorities. For instance, people living or working there have exceptional access to international broadcasts from CNN and BBC as well as to search engines, such as Google and Yahoo, with no apparent interference.

Nonetheless, guarded by armed police and separated from surrounding neighborhoods, the complex is never completely free from institutional regimentation. There is very strict entry control at the main gate. All visitors are required to register at reception with a valid identity document. In fact, DRC is state-owned real estate affiliated to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The residential and working spaces within DRC are rented only to foreign nationals or organizations. Chinese citizens are not usually allowed to enter the compound unless they are invited by individuals or organizations based in DRC. To some extent, the guarded gate still creates a physical and ideological boundary which naturalizes the division between China and foreign countries despite various nonofficial artistic and cultural activities held within DRC which have been fostering transnational transcultural communications since the 1970s. In association with deliberately chosen case studies, this article will examine the ambiguous and paradoxical character of DRC, which traverses the clear line of demarcation between domestic and foreign, and official and nonofficial.

As for the apartment unit known as DRC No. 12, it was first rented as a private office by the organization’s founder Peng Xiaoyang, a former lawyer with a Canadian passport.1 Born and brought up in Beijing, Peng has been friends with many artists with whom he grew up from a young age. In the winter of 2015, after hosting an event in memory of the late Chinese artist Feng Guodong, Peng decided to turn the unit into a nonprofit art space. Thus far, DRC No. 12 has held twenty-six exhibitions, offering diverse angles of vision on the spatial, historical, sociopolitical, and cultural specificities of the site. In a way, DRC No. 12 easily calls to mind some other nonprofit independent art spaces in Beijing, including Arrow Factory (2008–19) which transformed a windowed storefront located in an old hutong area into an exhibition space for displaying commissioned site-specific installations to cultivate generative interactions with the neighborhood.

However, it is the dual residential and diplomatic nature of DRC No. 12 that makes it a distinctive art space which brings to the fore the dynamic local-global entanglements investigated in this article. Due to the strict entry control at the main gate, the exhibitions held at DRC No. 12 can only be visited by invitation. Interested viewers can make an appointment online to obtain an invitation in advance. While exhibitions are on, staff members at DRC No. 12 are required to come down to the gate multiple times a day to take in registered viewers. According to Peng, the “by invitation” stipulation also enables the space to avoid or circumvent the bureaucratic procedures for acquiring authoritative permissions from relevant state institutions for public exhibitions.2

Moreover, DRC No. 12 has its own working system for selecting and commissioning exhibitions. Each year, an artistic committee, comprised of a different group of three or four artists and art professionals, sends invitations to artists whose practices, based on the committee’s research, are likely to engender certain productive interactions with DRC No. 12. At times, the committee also receives unsolicited submissions from artists who are willing to undertake the complexities of organizing an exhibition in the space. According to records, not every artist who submitted a proposal ended up having an exhibition at DRC No. 12. Nor did every artist accept the invitation from the committee. By far, every successful case has been developed and finalized through several months of in-depth conversations between members of the committee and the artist.3 Nevertheless, the committee only gives suggestions on the exhibition program and never make any curatorial interventions. Apart from a few exceptions, most of the artists have taken on the role of both the maker and curator of his or her exhibition.4 As for its daily operation and exhibition production, DRC No. 12 receives funding from private donors on the understanding that, as Peng indicates, “they have no say in what we do and are not allowed to recommend artists.”5 For Peng, such non-interfering support from donors is important for an art space which aims to create an environment for art production free from commercial pressures.6

This article aims to draw a generative parallel between two multimedia exhibitions presented at DRC No. 12 in 2016 and 2017, respectively, which offer an insight into some initial ideas that undergird the establishment and subsequent development of this unique art space located within a semi-official diplomatic domain in Beijing. My discussion investigates how the works presented at DRC No. 12 construct a “migratory” site of aesthetic encounters—where things, bodies, and images are set in motion physically or conceptually, unsettling any notions of spatial stability and temporal continuity—and how the exhibitions held in the space provoke critical reflections on unprecedented cross-border flows and exchanges on the basis of people’s site-specific artistic engagements in close relation to their quotidian experiences of life, making it possible to reconsider and reconfigure the connections and boundaries between private and public, past and present, and local and foreign. This article also delves into the ways in which DRC No. 12 explores and demonstrates a glocal model of art and exhibition making, concurrently aligning with and disrupting a range of institutional apparatuses of supports, constraints, and controls at the local, national, and transnational levels.

The Migratory, The Glocal

In this article, the notion of “migratory” is not necessarily tied to migrants or literal physical acts of migration. Rather, it considers how the site-specific art practices conducted at DRC No. 12 engender affective situations of border crossings in both a material and discursive sense. The analysis of the chosen exhibitions draws upon the scholarly discussion of “migratory aesthetics” that first came to the fore through a series of writings published around the late 2000s by a group of artists, cultural theorists, and art historians, including Mieke Bal, Sam Durrant, Catherine Lord, and many others. According to Durrant and Lord, migratory aesthetics “suggests the various processes of becoming that are triggered by the movement of people and peoples: experience of transition as well as the transition of experience itself into new modalities, new art work, new ways of being.”7 The works of art, which are studied in relation to migratory aesthetics, mobilize people’s kinesthetic and multisensory engagements, giving rise to open-ended ontological, epistemological, and aesthetic inquiries into the increasingly uprooted and movable state of contemporary life. Meanwhile, Bal proposes to understand migratory aesthetics as “a non-concept, a ground for experimentation that opens possible relations with ‘the migratory,’ rather than pinpointing such relations.”[Mieke Bal, “Lost in Space, Lost in the Library,” in Essays in Migratory Aesthetics, 23.] In line with these scholarly works, this article considers how DRC No. 12 as an exhibition space allows artists and viewers to engage with and reflect on multiple migratory conditions through their on-site practices of making or perceiving art which cannot be “grasped in terms of any given notion of stability,” revealing the contingency and mutability of one’s sense of identity, place, history, and culture.8

As for the term “glocal” or “glocalization,” it was first coined by British sociologist Roland Robertson to shed light on the important role of the local in generating cultural heterogeneity to contest the homogenizing effects of globalization.9 For Robertson, “the very idea of locality” is never simply cast as “a form of opposition or resistance to the hegemonically global.”10 Instead, the local and the global are mutually implicated, co-constructed and interdependent, and their relations could vary at different times and in different contexts. However, as scholars such as George Ritzer and Victor Roudometof have suggested, Robertson’s discussion is lacking in thorough consideration of the shifting power dynamics among diverse local and global forces which make it possible to destabilize and reformulate the systems and rules that govern the existing world order.11 Moreover, Robertson does not make it clear how practices conducted in a specific location and cultural circumstance might unsettle and challenge “the increasingly global ‘institutionalization’ of the expectation and construction of local particularities.”12

Developed from Robertson’s work, Canadian political philosopher James Tully configures “glocalization” as an engaged, democratic, and de-imperialized alternative to the Western-oriented ideals of cosmopolitanism and globalization which have been primarily predicated on the deterritorialized implementation of a universalizing system regarding international law or free trade that still ultimately favors powerful interests.13 Tully proposes to embrace the extensive and diverse localized grassroots practices outside traditional institutions at both national and international levels, which can lead to contestations, disruptions, and reconfigurations of existing geopolitical and sociocultural structures so as to construct “a world without end” in dialogical ways.14

This article is grounded in Tully’s critical exploration of “glocalization.” Although none of the works presented at DRC No. 12 directly addresses civic engagement or practical strategies of nonviolent disobedience in a political sense as investigated by Tully, they cultivate similar forms of locally grounded and transnationally oriented public engagements and collective commitments in and via site-specific processes of artistic production and reception. In addition, given its special indeterminate sociopolitical status in between domestic and foreign, DRC could be a compelling location to explore the formation of divergent glocal experiences of transnational transcultural connections, crossings, and collisions both within and beyond institutional practices.

55 Days at Peking

The first exhibition under discussion is 55 Days at Peking, which reconceived and reformulated a historical incident—the fifty-five-day siege of the legation quarter in Beijing during the Boxer Rebellion. The artist Ni Haifeng moved to Amsterdam in the early 1990s. Since then, his persistent negotiations with two remarkably different cultures and nations have provided him with a distinctive insight into China’s complex relations with foreign powers over the past two centuries.15 For Ni, DRC reminds him of Dongjiaominxiang, an old hutong area in Beijing where foreign legations were concentrated during the late Qing Dynasty, and where many diplomats, their families and guards, as well as Chinese Christians, resided.16 The siege of this legation quarter by the Boxers began on June 20, 1900. On the following day, after Empress Dowager Cixi issued a declaration of war against foreign powers, troops of the Chinese Imperial Army started to join the Boxers in attacking the foreign legations, although the attacks were mainly conducted in a fitful and piecemeal fashion.17 The siege was eventually ended by the armed invasion of the Eight-Nation Alliance on August 14, 1900.

In Ni’s view, the Boxer Rebellion was a controversial anti-foreign and anti-Christian grassroots movement in Chinese history.18 The official Chinese historical writings tend to attach more importance to Western colonial aggression rather than hostility and xenophobia incited from within Chinese communities.19 When doing research for the exhibition, Ni was drawn to the 1963 American historical epic film 55 Days at Peking. The title of the film highlights the exact timeframe of the siege which was especially reconfigured by the artist in his work to complicate and diversify viewers’ embodied perceptions on the exhibition site. Unlike some other films produced in Chinese contexts on the Boxer Rebellion which engender strong patriotic sentiments by exacerbating feelings of injured national pride and humiliation, 55 Days at Peking, according to the artist, could give viewers of his exhibition a unique entry point to revisiting and reinventing a past incident beyond confined national and cultural circumstances.20 In addition, by naming his exhibition after a film with substantial plots that are primarily built upon cinematic fabulations, Ni intended to open up different possibilities for viewers to generate their own interpretations without necessarily aligning with any accounts of historical “truth.”21

As indicated earlier, migratory aesthetics is not merely associated with art practices that address actual experiences or conditions of migration. More importantly, the relevant discussion investigates the ways in which works of art might engender an unstable but generative state of permanent movement, making it possible to transgress and reconstruct spatial, temporal, geographical, and cultural boundaries in an iterative manner.22 As for the exhibition—55 Days at Peking, Ni transformed DRC No. 12 into a migratory aesthetic site where the history of the Boxer Rebellion was not brought to the fore as objective, absolute facts, but rather constituted and reconstituted across time and place by virtue of the embodied embedded contributions from himself and other individuals to the work’s on-site materialization that gave rise to divergent perceptions and understandings.

The exhibition opened on June 20, 2017, and ended on August 14 to align with the exact duration of fifty-five days of the siege that occurred at Dongjiaominxiang 117 years before. The two-bedroom apartment was spatially arranged into a temporal structure. On wall-mounted flagpoles in the west side bedroom were the black-and-white navy ensigns of the eight nations invading Beijing in 1900, which included Japan, Russia, Britain, France, the United States, Germany, Italy, and Austria-Hungary. The removal of color from the ensigns by the artist could allude to a faded past that was also revitalized through newly cultivated site-specific relationships with DRC No. 12. Walking along and across the row of flags, viewers were prompted to contemplate the historical meaning of the ensigns in association with the intricate intertwining of trade, war, and imperial expansion that led to both connections and conflicts across national and regional borders. In the bedroom on the east side, seventeen contemporary national flags in full color were suspended from the ceiling. Following the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire members of the Eight-Nation Alliance had morphed into a roster of a total of seventeen countries: Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia (which further divided into Czech and Slovakia), and Yugoslavia (which split into Croatia, Montenegro, Serbia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Macedonia).

In the living room, a mounted monitor screened the film 55 Days at Peking with no soundtrack and on an extremely slow playback speed, which stretched the duration of the film to 1,320 hours to coincide with the fifty-five-day duration of both the historical incident and the exhibition at DRC No. 12. On multiple occasions, viewers reported that they had simply seen film stills displayed on the screen. The forward motion was only recognized if viewers spent quite some time observing the footage. The film, produced by Samuel Bronston and directed by Nicholas Ray, was mostly shot in Spain, where a cinematic Chinese environment was fabricated in a foreign territory. With this in mind, it follows that the on-site encounter at DRC with the decelerated, mute footage could engender various forms of cross-border and cross-cultural displacement. Furthermore, all major roles in the film, including Cixi and Rong Lu, were performed by Western actors and actresses wearing heavy makeup, whereas the extras playing the masses of the Chinese people were Chinese immigrants and mobile workers sourced from different cities across Spain. Released in 1963, 55 Days at Peking received a considerable number of negative critical reviews pointing to its lack of historical accuracies.

As Bal has discussed in a different context, conditions of slowness created through technological interventions in lens-based works allow viewers to realize how the perception of art requires time; one’s affective engagement with images or objects as a process could be far beyond what one instantly sees “out there.”23 Thus, for Bal, the interruptive manipulation of time with lens-based media can foreground people’s embodied sensuous involvements in the continuous artistic production of meanings, which makes it possible to undo or enrich fixed visual representations. As for Ni’s appropriation of the film 55 Days at Peking in the exhibition, the slow-motion effect prolonged viewers’ perception of the footage on the screen, complicating their identifications with the featured characters beyond preconceived stereotypes. Moreover, this historical film shot in a foreign environment outside China and subsequently decelerated for the exhibition to interrupt and intensify the immediate on-site experiences of viewers at DRC No. 12, engendered discrepancies that blur the clear division between past and present, near and far, and image and reality. In this way, Ni’s practice posed a challenge to any linear conception of history stably bound to a particular place and culture.

The corridor at DRC, which connects the two main bedrooms, could be perceived in Ni’s exhibition as a pathway linking the past to the present. Two parallel rows of fifty-five numbered dates in month/day/year format for both 1900 and 2017 were printed on the walls starting in the corridor and extending throughout the entire site. During the exhibition period, images, historical texts, and newspaper clippings related to what happened on each date in both 1900 and 2017 were continuously added to the walls. The 1900 timeline was centered around materials about the Boxer Rebellion while materials in the more contemporary timeline had a wider focus. In the gradual adding of materials, the two combined timelines each had their own day-to-day expansion, giving rise to various perceptions and understandings regarding not only the siege of the foreign legations in 1900, but also fragmented traces of life in different parts of the world in 2017.

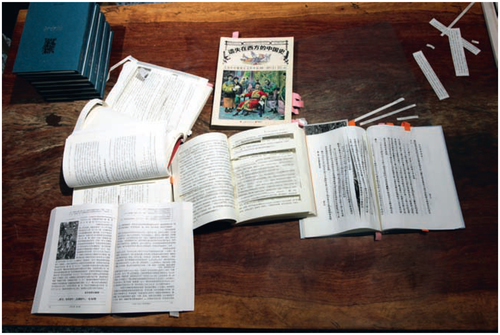

In preparation for the exhibition, the artist purchased a range of books on late Qing history published in different historical times. In addition to the ones written in Chinese, Ni also bought a great number of Chinese translations of books originally published in a foreign language to offer different insights into the history of the Boxer Rebellion beyond the Chinese context.24 On each day of the exhibition, Ni and staff members at DRC No. 12 spent time reading the books and selecting relevant content. They then cut paper strips and images out of the books to paste onto the walls. The books were piled on a table in the living room, giving clues to the sources from which bits and pieces of information had been found. Without embracing any specific interpretations of the Boxer Rebellion, Ni’s work was intended to engender a diverse array of voices and perspectives based on people’s immediate on-site identification and (re)formulation of a large amount of visual and textual materials.

By contrast, the 2017 timeline incorporated a much wider variety of content about current affairs, entertainments, sports, domestic politics, and international relations. Displayed on the walls were mostly clipped headlines and front-page images from daily newspapers issued in different cities and provinces across mainland China. A heap of outdated leftover newspapers, accumulated day by day, was also displayed in the living room. Confronted with myriad news reports on major or minor incidents occurring in different times and places, viewers were enabled to reflect on their relationships with/in multiple interlacing spatiotemporal worlds beyond regional and national borders. The exhibition site was, thus, turned into a productive domain of localized public diplomacy, giving rise to divergent views and opinions on sociopolitical and cultural issues both at home and abroad despite possible misunderstandings and disagreements. This condition recalls another important dimension of migratory aesthetics, which, as Bal and Miguel Á. Hernández-Navarro have discussed, underscores the capacity of art to create a platform of not only affective relatedness, but also instability and potential conflict that allow both artists and viewers to “experience and participate in the tensions of a non-consensual society” without ever reaching a finalized reconciliation.25

Furthermore, as Bal has argued in association with migratory aesthetics, works of art do not “leave the viewer, spectator or user of art aloof and shielded, autonomous and in charge of the aesthetic experience.”26 The exhibition 55 Days at Peking, in this sense, materialized migratory aesthetic situations where the artist, staff members at DRC No. 12, and viewers could situate themselves always in transit “from one place and time to another, as a permanent state of impermanence.”27 Whereas the artist and staff members took part in the ongoing (re)configuring of the exhibition by maintaining its material setting, and adding new content to it on a daily basis, viewers walked through the whole apartment and paused at different moments to perceive, identify, and apprehend a hybrid of things, images, texts, and video clips with regard to recent affairs taking place in 2017 as well as varied interpretations or representations of the Boxer Rebellion with a specific focus on the siege of the foreign legations in 1900. Given the remarkably large quantity of items on display, everyone on the exhibition site could be engaged in the persistent processing of information that is devoid of a comprehensive understanding, as there could always be certain materials neglected or not yet taken into consideration.

Based on the constructive practices of multiple embodied individuals through making and perceiving art, histories (whether recent or remote) were rendered specifically tangible and sensible across times and places. In doing so, Ni, with his exhibition, revealed the inevitable partiality of historical knowledge production always open to iterative reinventions and reformulations with difference. Meanwhile, stimulating site-specific kinesthetic experiences of both connections and crossings beyond confined geographical, sociohistorical, and cultural contexts, the exhibition gave rise to a glocal form of public engagement which could destabilize the universalizing narratives of globalization grounded on the institutional practices of governance and regulation that often lock nations and individual bodies into fixed and hierarchically organized structures of control and subordination.28

Diplomatic Residence Compound

Compared with Ni’s 55 Days at Peking, Wang Youshen’s exhibition, titled Diplomatic Residence Compound (August 30–November 6, 2016), brought additional attention to people’s quotidian experiences of life dynamically intertwined with the increasing movements of goods, capital, and services across time and space. Wang’s inspiration for the exhibition stemmed from an international post office located next to DRC. In the 1980s and early 1990s, people had to come to this particular branch of China Post—the state-owned postal system in Mainland China, to send international mail or pick up letters and parcels from overseas which demonstrated its authoritative status for cross-border communication and exchange. Nevertheless, in recent years, the official postal services operated by China Post have no longer been the only option. The rise of many private courier companies has considerably enhanced the nationwide logistics networks that extend to nearly every corner of the world.29

When preparing the exhibition, the artist first borrowed a few items of furniture, including a double bed, a desk, and a few chairs, from several neighboring studio apartments within the complex and placed them in DRC No. 12 to make the space look more like a personal home. Wang did not strictly follow the original spatial layout of the unit. The double bed was placed in the living room, which was temporarily transformed into a main bedroom for the exhibition. The desk was placed in the original main bedroom on the west side, which was arranged into an office. The bedroom on the east side that typically functioned as a meeting room for the art space remained a meeting room. Over the eighty days starting from August 16, the artist sent eighty-five packages of various sizes from his home, studio, and workplace via sixteen different delivery companies to the owner and founder of DRC No. 12, Peng Xiaoyang. Each package could contain multiple items and Peng received at least one package daily until two days before the end of the exhibition on November 6.

Most of the delivered items were photographs, videos, and documents created or collected by Wang in association with his own experience of life or a range of local and international incidents that once caught his attention. His experience of working as a media worker at the Beijing Youth Daily for three decades, instilled in him the regular habit of compiling and archiving materials that he considered meaningful and important. Other things sent to the space included household or personal items such as books, postcards, CDs, old calendars, clocks, light fixtures, rugs, blankets, bed sheets, pillows, food recipes, and bottles filled with homemade health drinks, with which the art space appeared like a typical home.

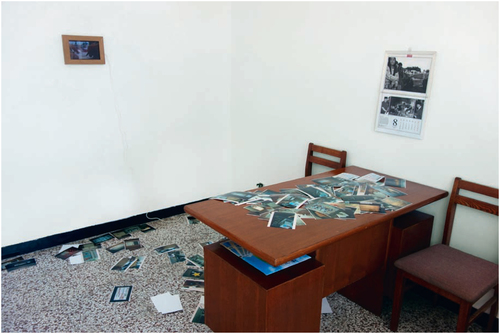

When the exhibition opened to the public on August 30, a variety of images, objects, and written documents were already on display around the space. Both sides of the corridor were covered by printed tracking records of the packages from pickup to delivery, whereas signed delivery bills were pasted on one side of the wall in the living room. Viewers could find some unopened parcels here and there on the ground. With a few more items added to the space every day, the exhibition was continuously being rearranged and reconfigured anew like an ongoing, open-ended event which involved contributions from not only the artist and staff members at DRC No. 12, but also embodied viewers, along with, of course, the couriers who possibly never realized their artistic engagements. After the exhibition, all deliveries were repackaged and sent back to the artist.

As indicated, almost everything exhibited on site had been created, used, or collected by the artist over a period of years. The objects carry Wang’s personal experiences of life and also, at the same time, recall the shared memories among a generation of people living in a rapidly developing Chinese society with/in an ever-shifting world environment. For instance, the blanket placed on the king-size bed in the living room is printed with a tiger on one side and a panda on the other, which was the trend in the 1990s in northern China. A carefully framed poster, featuring the Statue of Liberty holding the World Trade Center towers in her arms, was left on the terrazzo floor arranged against the wall as if it had just been taken out of the shipping box. Brought back by a friend from America as a gift to the artist in 2001, it is one of the 300 limited edition print series produced by Robert Rauschenberg shortly after the 9/11 terrorist attacks.30 Also on the wall was a poster for a 1985 exhibition held in Beijing which first introduced the artist to scenes of everyday life in New York City.31 By opening a personal residence to viewers this exhibition collapsed the very distinction between private and public, and individual and communal. In this regard, the artist’s approach is reminiscent of the “apartment art” or “compound art” phenomenon which played an important part in the development of contemporary art in mainland China between the 1970s and 1990s.32 Before residential housing became commercialized, multiple groups of Chinese artists made use of their private households within, according to Gao Minglu, “government-owned residential complex,” whether building blocks or courtyard compounds, to conduct art experiments outside official art venues.33

Wang’s Diplomatic Residence Compound exhibition especially recalls the works of apartment art discussed by Gao in association with “household art practice and display” in the 1990s, which differ from earlier “family salon” exhibitions held between the late 1970s and the mid-1980s and conceptual art “projects on paper” circulated through low-budget private publications during the late 1980s and the first half of the 1990s.[Ibid.] The recourse to “household art practice and display” was due to the lack of both official support and a well-developed domestic art market, and therefore many artists in the 1990s started to create “home-based” installation works from affordable, seemingly trivial but meaning-making household materials closely related to their quotidian experiences of life.34 Presented at home or within courtyard compounds for a short period of time to a few fellow artists and invited friends, these works engendered alternative perspectives to consider grand narratives of economic development and urban modernization that were pervasive in a fast-changing Chinese society. In fact, some of Wang’s earlier works, like Nutritious Soil (1994), are studied by Gao as paradigmatic examples of “household art practice and display.”35 In 1994, Wang bought bags of nutrient dense soil originating from the forest region in northern China. The artist spread a thick layer of the soil, often used for growing precious indoor plants, on the floor of the kitchen, dining room, and bathroom of his family’s apartment in Beijing. In the following few days, the artist and his family members lived and worked at home as usual while smelling and stepping on the “carpet” of soil. With this piece, Wang provoked reflections on how soil, which carries traces of people and places, could foster tangible sensuous experiences of relatedness across a clear divide between interior and exterior, nature and culture, as well as placement and displacement.

In an interview included in the DRC exhibition catalog, Wang made a subtle distinction between historical practices of apartment art and recent projects conducted at DRC No. 12. In his view, artists’ varied experiments with apartment or compound art during the 1980s and 1990s were more or less a passive choice due to the difficulty of finding suitable venues within museums or art galleries to exhibit their works to the public.36 By contrast, the exhibits presented at DRC No. 12 have been built on participating artists’ proactive exploration of innovative ways of art and exhibition making.[Ibid.] In the case of Wang’s DRC exhibition, by the strategic use of logistics networks, he gave rise to relationships both on and off the exhibition site with diverse individuals far beyond a familiar circle of artists and art professionals. In addition, unlike his other apartment-based works, such as Nutritious Soil, which have been recreated and reformulated in multiple exhibition venues to engender new connections with people, places, and cultures, the arrangement of things in Diplomatic Residence Compound made viewers’ immediate multisensory engagements with the surrounding material environment nonreproducible in a different space.37

The west side of the DRC space receives very good sunlight in the afternoon. At times, because of the strong light, visitors could only squint towards the large, curtainless windows in the living room, which, for the exhibition, were partially covered by a collection of rectangular pieces of paper with images and diagrams about the location and spatial layout of multiple residential apartments in Beijing. The artist had gathered these in 2003, when he was planning to purchase a home in the city. All the images and diagrams were pasted onto the windows with their backside facing toward viewers. On each, the artist had handwritten a number. Under bright sunlight, the papers created shadows projected onto the opposite wall, forming a vague grid structure.38 The frontside of each could be seen from outside on the open balcony. This part of the work enabled viewers to forge affective and tangible connections with not only the material environment of the site, but also well-organized images and diagrams concerning a significant number of residential units scattered around the city, which gave an insight into the real estate boom in Beijing that started in the early 2000s, especially after the city was awarded the hosting rights to the 2008 Summer Olympics and China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO). In Wang’s work, seemingly inconspicuous items could be arranged in specific ways that would engender reflections on how people’s lives were implicated in varied local, national, or even international social-economic conditions.

Attached to the inside of the main door were two photographs exchanged as New Year’s cards between the artist and an Australian couple who first brought him into DRC in the 1980s. In contrast to official discourses of diplomacy that often center around state-to-state relations, the artist revealed his personal experience of “diplomatic” engagement by sending items related to his transnational connections back to the place from which they originated. In the bathroom, a group of photographs collected by the artist in 2013 were set to soak in water in the sink next to the toilet. These photographs capture retired NBA star Dennis Rodman arguing with a CNN host in a live television show regarding Rodman’s visit to North Korea. Rodman’s trip was undoubtedly coded diplomatic, receiving considerable media and public attention while arousing certain controversies. By coincidence, CNN’s Beijing Bureau is located just one floor above DRC No. 12. Over time, these soaked photographs became blurry and eventually faded out. With this part of the work, the artist raised questions about the timeliness, reliability, and accuracy of news reports, which are less about absolute truth and more about the rhetoric of representation and interpretation. Compared with the content of an outdated television broadcast, the fading status of these soaked photographs at different moments of time could affect viewers in a much more compelling and substantial manner, putting forward a way of knowing, becoming, and relating on the basis of one’s embodied, embedded engagements with the surrounding world. In addition, in the exhibition, viewers could find a great number of photographs of the artist taken in varied locations in 1985, 1991, 1997 and 2001 respectively, and also encounter the artist in person, as he was present at DRC No. 12 during the show.

Many of the items displayed in Diplomatic Residence Compound could refer to multiple times and places. This condition of spatiotemporal expansion was further intensified and complicated by Wang’s strategic use of well-developed logistics networks. Via different courier companies, it took one to three days for the packages sent by the artist to reach DRC No. 12. Depending on the location of each company’s warehouse for centralized dispatch, many items might have initially left the city and then travelled back across several districts before arriving at the final destination. The relevant information was revealed to viewers through the tracking records pasted onto the walls of the corridor. On occasions, some shipments, having suffered unexpected damage in transit, ended up taking extra time for settling compensation, which also engendered temporalities of waiting and suspension in stark contrast to the smooth linear conception of time usually associated with express delivery services that underline speed and efficiency.39

Similar to 55 Days at Peking discussed earlier, Wang’s exhibition paid no particular attention to real-life situations of migration. Instead it facilitated site-specific but migratory aesthetic encounters which multiply, in Bal’s words, “temporal and spatial coordinates beyond the possibility of fixation.”40 Far more than simply embracing a free-floating form of art practice completely liberated from all kinds of spatial, temporal, sociohistorical, cultural, and geopolitical constraints, the analysis in this article tends to shed light on the affective material capacity of art to contest and reconfigure existing boundaries and categorical divisions which are often set up to fix or restrict people’s perceptions and understandings of their own existence with/in an ever-changing surrounding environment.

As mentioned at the very beginning of this article, DRC is an ambivalent domain marked by both freedom and constraint. Despite certain privileges enjoyed by people living and working there, DRC is not quite an exterritorial area completely outside the straitjackets of governmental regimentation. According to the artist, some items were found to have been examined, unwrapped, and repackaged prior to the final delivery.41 The items presented in the exhibition could have passed through multiple forms of authoritative control. Interestingly, the artist sent a significant number of his packages via EMS—a subsidiary of China Post set up for express mail services. As indicated in the exhibition records, the EMS shipments took one or two additional days to reach the art space. In consideration of the sensitive location of DRC close to Tiananmen Square in central Beijing, it’s very possible that EMS, compared with private companies, would conduct more stringent checks, resulting in extra processing time.

Rather than posing a direct challenge to state systems of governance and regulation, Wang’s exhibition either circumvented them or, when possible, reformulated them with nuanced interventions. In his discussion of glocalized democracy, Tully proposes a cooperative and dialogical model of citizen-governance relations predicated on the continuous practices of contestation and negotiation through which members of the general public are not excluded from but actively participate in the iterative interdependent (re)constitution of various institutional systems anew.42 With his work, Wang materialized a glocal migratory site marked by both physical mobility and conceptual fluidity that destabilize any pre-given spatiotemporal, sociopolitical, and cultural boundaries. Viewers of different backgrounds could create their own situated relationships with a variety of the items collected, created, or compiled by the artist, which, in turn, enrich and expand the ongoing material and discursive configuration of the exhibition over its 80-day span both on- and off-site, as well as both within and outside institutional controls regarding domestic governance, diplomatic practices, and postal services.

Coda: A Glocal Model of Migratory Site-Specificity

Undoubtedly, site-specificity has been a central issue explored in the exhibitions presented at DRC No. 12, which, given the special location of the space within a semi-official diplomatic domain, also involves a productive transnational and transcultural dimension. This resonates with while also departing from the scholarly discussion since the 1990s of site-specificity closely tied to the proliferation of biennales, art fairs, and artists’ residencies that has led to unprecedented travel and migration in the art world. In her 2002 path-breaking book One Place after Another: Site-specific Art and Locational Identity, Miwon Kwon proposes a discursive model of site-specificity unmoored from clearly identified geographical and material contexts. Her discussion offers insight into the ways in which recent art practices activate public engagements with a range of sociopolitical issues, constituting a discursively determined field of “knowledge, intellectual exchange, or cultural debate.”43 She brings particular attention, especially in the second half of the book, to the rise of socially-engaged community-based art practices concomitant with the growing demand on “an intensive physical mobilization of the artist to create works in various cities throughout the cosmopolitan art world.”44 Basically, artists have started to travel to different places around the world and collaborate with institutions or deliberately chosen communities to create artworks that reveal a particular aspect of local life and culture. In the meantime, as Kwon warns, the specific socioeconomic and institutional conditions that facilitate such privileged mobility of artists to develop connectedness with/in multiple localities have been rarely acknowledged and thoughtfully investigated.

In his review of the book, T. J. Demos indicates that Kwon’s discussion, based on the study of selected works of art, articulates an anti-essentialist perspective, which raises questions about any fixed and stable conception of site, identity, or community “essentially bound to the physical actualities of a place.”45 However, according to Demos, the investigation of discursively determined site-specific works of art, at times, turns out to be “completely uprooted from material practice, as well as from its historicity, which suggests a limitation in Kwon’s analysis.”46 In this regard, built upon her investigation of migratory aesthetics, Bal suggests that “since art making is a material practice, there is no such thing as site-unspecific art.”47 In other words, for Bal, the increasingly migratory production, distribution, and reception of art cannot and should not obscure the affective nuances of locally grounded experiences.48 Unlike Kwon, whose discussion foregrounds a fluid and mutable understanding of discursive site that undergirds the worldwide itineraries of traveling artists, Bal attaches particular importance to the localized material conditions of site-specificity inseparable from the immediate and lively sensuous engagements of both artists and viewers across difference and distance in spite of possible unsettledness and discord.

In this article, the investigation of glocal site-specificity is more aligned with Bal’s discussion. It has less to do with the unimpeded mobility celebrated in the contemporary art world than with intermittently grounded material relationships created through works of art in varied local environments which simultaneously evoke manifold situations of movements and exchanges beyond national and regional borders. Thus, this study offers an alternative perspective to consider the ever more globalized institutionalization of art through well-established systematic practices of museums, art fairs, and biennales that prioritize efficiency and flexibility as well as cross-border portability and connectivity. Through the analysis of the works by Ni Haifeng and Wang Youshen, this article is also intended to cast new light on the creation and exhibition of contemporary Chinese art in transnational transcultural circumstances outside the typical venues of art fairs and biennales. More importantly, facilitating materially-embedded and sensuously-affected site-specific experiences of migratory artistic engagements, the exhibitions presented at DRC No. 12, I would argue, bring to the fore a glocal model of public participation in and via the persistent construction of connections across times, places, and cultures without evading incongruities and disparities. This forms a stark contrast to the practices of assimilation and incorporation conducted by national or international institutions which forge unity, solidarity, and cohesion on the basis of sameness and agreement while suppressing alterity and conflict.

Vivian K. Sheng is assistant professor of art history at the University of Hong Kong (HKU). She is currently completing her first book, Fantasies of Homemaking: Art, Migration and Transnational East Asia. Her writings have appeared in Third Text, Sculptural Journal, Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art and INDEX JOURNAL. [Art History, The University of Hong Kong, 1020 Run Run Shaw Tower, Pokfulam, Hong Kong, vksheng@hku.hk]

- Since March 2024, the ownership and all related rights of DRC No. 12 have been transferred from the founder, Peng Xiaoyang, to the newly established Board of Directors. For more information, see “DRC No.12 Established A New Board of Directors.” DRC No. 12, 2024, accessed on March 22, 2024. ↩

- Peng Xiaoyang (founder of DRC No. 12), WeChat phone call with the author, December 1, 2023. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- A few artists invited a guest curator. ↩

- Peng, “Inside DRC No.12 + Bunker, Beijing,” interviewed by Meng-Yun Wang. The Face, June 20, 2019, accessed on December 8, 2023. ↩

- Peng, WeChat phone call, December 1, 2023. ↩

- Sam Durrant and Catherine M. Lord, “Introduction,” in Essays in Migratory Aesthetics: Cultural Practices between Migration and Art-making, eds. Durrant and Lord (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2007), 11–2. ↩

- Bal and Miguel Á. Hernández-Navarro, “Introduction,” in Art and Visibility in Migratory Culture: Conflict, Resistance, and Agency, eds. Bal and Hernández-Navarro (Thamyris/Intersecting: Place, Sex and Race, vol. 23) (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2011), 10. ↩

- Roland Robertson, Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture (London: Sage, 1992), 173; see also Robertson, “Glocalization: Time-Space and Homogeneity-Heterogeneity,” in Global Modernities, eds. Mike Featherstone, Scott Lash and Robertson (London: Sage, 1995), 25; 30. ↩

- Robertson, “Glocalization,” 1995, 29. ↩

- Victor Roudometof, “Theorizing Glocalization: Three interpretations,” European Journal of Social Theory 19 no. 3 (2016), 393; George Ritzer, “Introduction,” in The Blackwell Companion to Globalization, ed. Ritzer (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2007), 6. ↩

- Robertson, “Glocalization,” 1995, 38. ↩

- James Tully, On Global Citizenship: James Tully in Dialogue (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), 73-79. See also Lee Ward, “Glocalism and Democracy in James Tully’s Critique of Cosmopolitanism and Imperialism,” in Cosmopolitanism and its Discontents: Rethinking Politics in the Age of Brexit and Trump, ed. Ward (London: Lexington Books, 2020), 163–64. ↩

- Tully, On Global Citizenship, 49. ↩

- Ni Haifeng, “Series Interviews–Ni Haifeng’s Exhibition,” in 12 Artists | DRC Triennial (2018.12.7-2019.2.17), exh. cat., eds. DRC No. 12 Artistic Group Members (Beijing: DRC No. 12, 2018), 81–82. ↩

- Ni, WeChat phone call with the author, December 2, 2023. ↩

- See Eric Ouellet, “Multinational Counterinsurgency: The Western Intervention in the Boxer Rebellion 1900–1901,” Small Wars & Insurgencies, 20:3-4, 2009, 510; 513; and David J. Silbey, The Boxer Rebellion and the Great Game in China (New York: Hill & Wang, 2012), 148–50. ↩

- Ni, 55 Days at Peking, exhibition catalog (Beijing: DRC No. 12, 2017), 8. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ni, WeChat phone call, December 2, 2023. ↩

- Ni, WeChat phone call, December 2, 2023. ↩

- Durrant and Lord, “Introduction,” 13. ↩

- Bal, “Activating Temporalities: The Political Power of Artistic Time,” Open Cultural Studies 2, no. 1 (1988): 88. ↩

- Ni, WeChat phone call, December 2, 2023. ↩

- Bal and Hernández-Navarro, “Introduction,” 11. ↩

- Bal, “Lost in Space, Lost in Library,” 23. ↩

- Bal and Hernández-Navarro, “Introduction,” 17. ↩

- Tully, On Global Citizenship, 58–59. ↩

- For more information about the development of postal services and logistics networks in mainland China, see “2016 Annual Express Market Supervision Report,” State Post Bureau, 2017, 6; 13–14. ↩

- Wang Youshen, phone call with the author, March 13, 2023. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Gao Minglu, “Chinese Apartment Art: Primary Documents from Gao Minglu Archive, 1970s–90s,” University of Pittsburgh, September 25, 2023, accessed on December 8, 2023; see also Gao, “From Elite to Small Man: The Many Faces of a Transitional Avant-Garde in Mainland China,” in Inside Out: New Chinese Art, ed. Gao (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 161. ↩

- Gao, “Chinese Apartment Art,” accessed on December 8, 2023. ↩

- Ibid.; See also Wu Hung, “A Domestic Turn: Chinese Experimental Art in the 1990s,” Yishu—Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art 1, no. 3, November 2002, 3; 6. ↩

- Gao, “Chinese Apartment Art,” accessed on December 8, 2023. ↩

- Wang, “Exclusive Interview—Wang Youshen: Teasing ‘Diplomatic’ from ‘Compound,’” compiled by Lee (pseudonym), Diplomatic Residence Compound, exhibition catalog (Beijing: DRC No. 12, 2016), 270. ↩

- ariant versions of Nutritious Soil have been exhibited in venues like Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt in 1996, Pao Galleries, Hong Kong Arts Centre in 1997, and Today Art Museum in Beijing in 2009. ↩

- The artist especially emphasized the interaction of his work and the apartment under remarkable natural lighting conditions. This part of the exhibition has also been briefly discussed by two critics in the review articles included in the exhibition catalog Diplomatic Residence Compound; see Su Wei, “Diplomatic Residence Compound at Sunset,” 200; and Zhang Linzhi, “Time and Space in the Diplomatic Residence Compound,” 238–39. ↩

- For instance, a porcelain pot once used by the artist to make health drinks was broken into pieces when it was shipped to DRC No. 12. The artist presented the broken pot along with a letter of indemnity in the kitchen. ↩

- Bal and Hernández-Navarro, “Introduction,” 11. ↩

- Wang, “Exclusive Interview,” 273. ↩

- Tully, On Global Citizenship, 49; 79. ↩

- Miwon Kwon, One Place after Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 26. ↩

- Ibid., 160. ↩

- T. J. Demos, “Rethinking Site-Specificity,” Art Journal 62, no. 2, Summer, 2003, 99; Kwon, One Place after Another, 164. ↩

- Demos, “Rethinking Site-Specificity,” 98. ↩

- Bal, “Lost in Space, Lost in the Library,” 25. ↩

- Ibid., 23–24. ↩