Contemporary Projects features original projects driven by artists, designers, or curators, highlighting diverse, critical forms of knowledge directly produced by art and design practices.

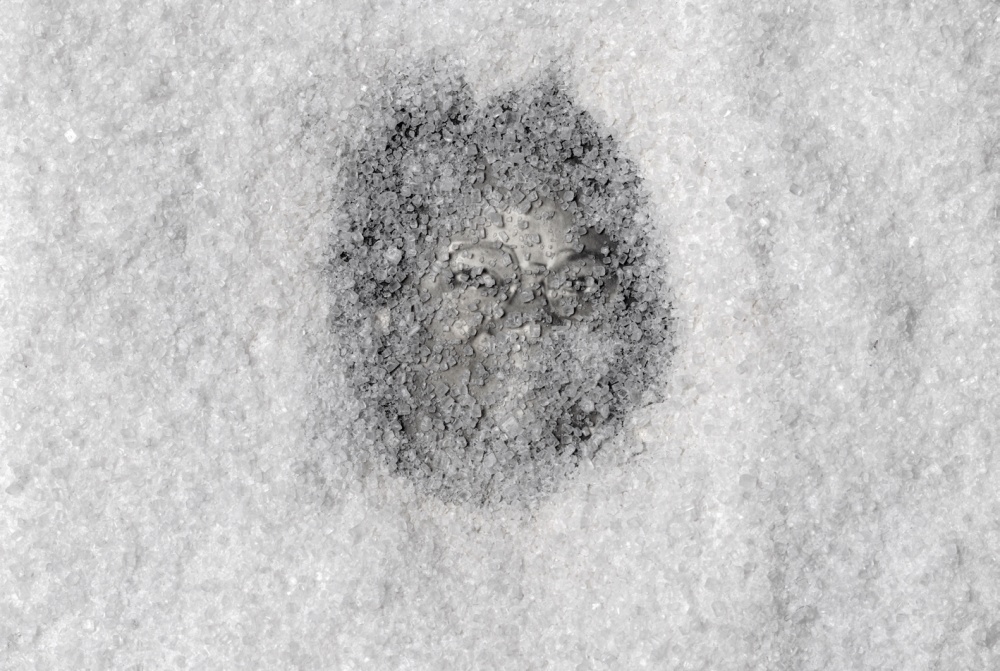

In Sweet Thing, I use sugar as a symbolic thread to weave a fragmented family album. Combining archival images of my Cuban ancestors with contemporary photographs taken on visits to their former homes, I create blurred visuals that echo the elusive nature of memory. As a repeated symbol in this project, sugar functions as a form of visual cacophony.

The series gathers family portraits, archival material, soundscapes, and interviews with my parents, alongside images of meaningful locations. From the remnants of my great-grandparents’ home in Matanzas, near the Triunvirato sugar plantation, where they were once enslaved—and now part of UNESCO’s Routes of Enslaved Peoples—to the rural settlements of Holguín and Las Tunas and the spiritual landscape of Havana’s Church of Our Lady of Regla, each site is both personal and historical. These are places marked by sugarcane and survival, where the soil itself carries the residue of bondage, devotion, and inheritance. Each piece reconstructs an uncertain past.

In this excerpt from the series, I focus on the women who anchor these histories—those whose strength and silence form the emotional and spiritual core of Sweet Thing. Their lives, marked by endurance and devotion, trace the contours of the island itself. Unlike traditional genealogical records, my process is nonlinear. Missing documents and eroded narratives force me to construct memory through place and imagery.

Sweet Thing explores displacement, survival, and the fragile nature of inherited memory. The title draws from a phrase once used in Cuba to describe the sugar harvest: “The excess of sugar produces bitterness.” A reminder that sweetness and suffering have always been intertwined.

I can picture my grandmother, born in 1898, as the proud yet humble daughter of former slaves, her tiny frame already brimming with quiet strength. From dawn until dusk, she moved between the kitchen hearth and the sunbaked fields. She raised ten children through sheer perseverance—though words on a page may have eluded her, her story was written in the lives she shaped and the legacy she passed on.

My late mother was born in a tiny settlement of fewer than ten houses in the eastern part of Cuba, surrounded by sugarcane. She was barely eight when her mother packed her off to Holguín’s grand townhouses, sent to polish silver and scrub floors so the family could survive. She stayed with those wealthy families until the world itself seemed to pivot in 1959, and then—like so many—she set her sights on Havana.

According to my mother’s stories, in one of the houses she worked, the mistress would go to the extreme of using a white glove to check that the dishware was spotless, even though the butler had already supervised.

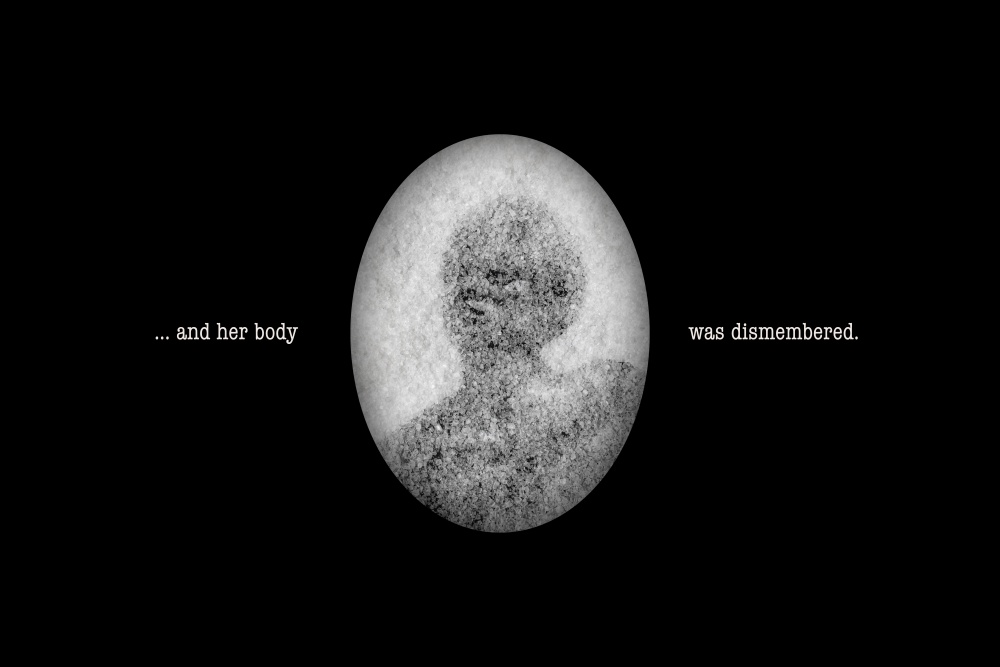

God Had Other Plans, 2025, photo installation/variable dimensions

My mother always loved dancing, but as her mother might say, “God had other plans.” So, she sent her to work and decided who her first husband would be.

My Aunt Coty spent her whole life around her house in Santa Ana de Cidra, raising six kids. She only had access to basic education when she was already an adult.

Less than a mile away from where my father was born, there’s a monument to the slave Carlota. She led a slave uprising in 1843. The house of the masters was set on fire, as well as part of the sugar mill and the bohíos of the batey. The rebellion managed to spread throughout the province of Matanzas. She died fighting in March 1844.

My great-great-grandmother, Isidra Pupo, lived to be 114 years old. She was taken to Cuba as a slave of unknown origin. After the abolition of slavery, she was a domestic servant. Despite her long life, there is no graphic testimony of her passage through this world.

I asked my older sister, “Do you know the origin of the last name Pupo in the family?” She said our grandmother Isidra worked as a maid in the house of a Pupo family. The lady was very nice, she taught her how to read and write, she said. Then she decided to name Isidra’s children Pupo.

Coda

At times, I wonder if retracing a past filled with unfinished stories is not unlike trying to nurture a tree whose roots have been severed—a gesture bound by hope yet fated by absence.

Jorge Luis Álvarez Pupo is a Cuban artist based in Belgium whose work explores cultural heritage, migration, identity, and legacy. Trained in literature and English language at the University of Havana, and in Photography at the International Institute for Journalism José Martí, he combines archival material with contemporary imagery to reconstruct personal and collective memory. His work has been exhibited internationally at Paris Photo, AIPAD, and Bozar Brussels, and is held in major collections, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Albertina Museum, Vienna.