This article originally appeared in Art Journal 84, no. 2 (Summer 2025)

Reading Sekula in Jerusalem

Like many courses on the history of photography in other universities, the one I deliver regularly at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem includes Allan Sekula’s 1986 essay “The Body and the Archive.” This seminal work is famous for its concretization of prevalent conceptions of photography and uses of cameras within a critique of the social sciences and their devastating applications in modern societies. Through the past four decades, Sekula’s essay has remained a rich source for the reconsideration of the role of photography in the structuring of both aesthetic and social conventions—such as “body” and “archive”—that are still commonly challenged by numerous artworks across mediums, biographies, and political viewpoints.1

We read Sekula’s text in class and discuss its main ideas, while considering their relevance to our own time and place. Now, as I am writing this essay, the wounds of the Hamas attacks on October 7, 2023, are still growing, and the consequent untenable destruction of Gaza by Israel seems unstoppable. The students in my class are a mix of Israeli Jews, Muslim and Christian Palestinians, and a few internationals that decided to stay here in spite of the war. This current deadly crisis in the traumatic national histories of Israel and Palestine is now debated on the international stage with an unprecedented breach of trust between the humanities and the human subjects of their political and critical theories; it feels as if the very project of understanding human beings (especially the cultural, philosophical, and historical means by which their identity as human is given and taken) has never been so challenged by the changing applications of the most basic ethical claims of humanist education. Some of these claims, obviously, stream also through works of contemporary art.

In what follows, I revisit “The Body and the Archive” vis-à-vis its current presentation in a particular pedagogic context, as well as its current connection to particular artistic practices of the past decade. “The Body and The Archive,” as I frequently have come to realize, is still considered a primary reading on how identities are formed, not only in and by the archive but also in and by the creative response the archive generates among artists. It is also richly relevant to my students despite the temporal gaps they face: the four decades that stretch between the 2020s and Sekula’s time, as well as the fourteen decades between today and Sekula’s main subjects of inquiry, the French police official Alphonse Bertillon and the English statistician and founder of eugenics Francis Galton.

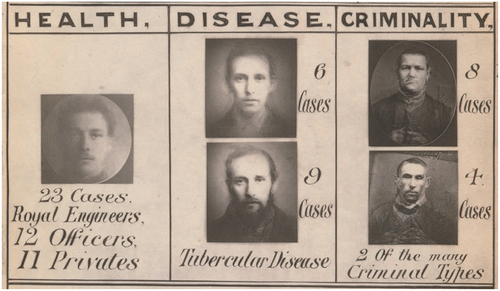

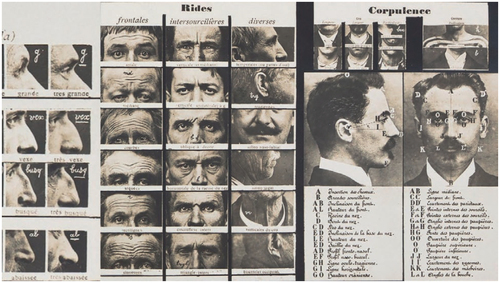

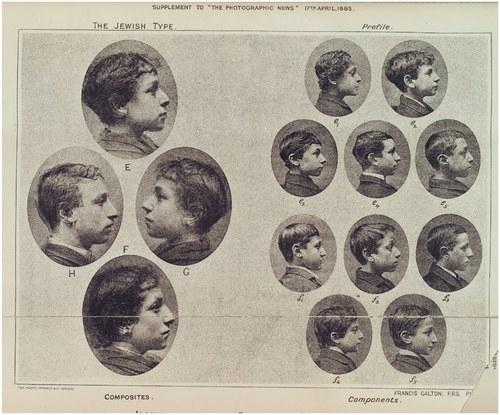

At the outset of Sekula’s essay, a combination of his view on the birth and evolution of photography with his ethical stand regarding the investigation of modern policing mechanisms is clearly formulated: The “presumed denotative univocality of the legal image” (for instance, in the photographic portrait) is employed through the systematization and rationalization of political, aesthetic, and intellectual discourses in the nineteenth century, instrumentally defining a new object—the criminal body; consequently, a more extensive “social body” is invented via specific camera-actions wrongly excluded from the disciplinary frameworks of art and art history.[Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” 346.] A whole set of assumptions and conclusions is then built on the visual logic inferred from innovative camera-based manipulations on the faces and bodies of those who find themselves on the wrong side of the law, as it were. Following Michel Foucault’s 1970s texts on the repressive machinations of power-knowledge and their effects over the human body, Sekula conceives of the very photographic act and resulting processes as primarily socially destructive. Exploring the historical ties of the camera with law enforcement, Sekula performs a deep dive into the different fascinating stories of Bertillon and Galton. Each invented a powerful criminological system which photographically records human facial features that would potentially match and prove the criminality of certain individuals. Importantly, Sekula’s essay does not end with Bertillon and Galton but rather with the prospective association he finds in their work with twentieth-century camera artists, such as Walker Evans, Martha Rosler, and Ernest Cole.

The link between the need to reconsider the histories of modernity—especially from a sociocritical perspective on visual mechanisms of identification and identity formation—and the most basic questions for contemporary artists (such as the ethics of documentation, the ontological traps of representation, the political dimension of creative expression, and the psychological consequences of certain modes of display) was at the heart of Sekula’s own creative practice as an artist. Across various different subjects and stories, Sekula’s multimedia installations have consistently exemplified, on the levels of both the mode of camera-expression and the eventual photo-production and gallery-display, “a materialist social history of photography, a history that takes the interplay of economic and technological considerations into account.”2 This same link—where historical investigation of the medium informs its present manifestations in the arts—is at the basis of the tribute proposed here to Sekula’s nearly forty-year-old essay.

In our recent class in Jerusalem, the reason that Sekula’s essay is so important to a syllabus on photography history seems to deviate from the rationale of disciplinary acknowledgment. Teaching “The Body and The Archive” calls for a certain ethical commitment that is not necessarily subjected to chronological tests of relevance. It is the commitment to watch humanity define its boundaries and call out when every act of epistemological border control cancels out bodies as illegitimate, illegal, or even nonhuman. It is the Foucauldian commitment to deconstruct power-knowledge clusters through seeing our part in their sanctioning, a project in which I hope to find myself and my students included. More principally, Sekula composes histories of art as visual responses, as critical encounters with images, in a similar fashion to what we actually do in class; it is the sort of encounter that Griselda Pollock defined as “framed by existing knowledges, by repressed knowledges, by questions that were not possible to frame and pose before but which are now not only possible but necessary.”3

Let me recall a somewhat surprising example from Sekula’s essay where the text unintentionally punctured our already fragile, conflict-laden present in class. In his investigation of Galton’s 1880s anthropometric method of composite photographs, meant to provide the definitive visual type of the average criminal, Sekula concludes with the “most successful composite as that depicting The Jewish Type,” which was applauded by Galton’s biographer, Karl Pearson, as “a landmark in composite photography.”4 Noting in retrospect the “line of influence that led from Anglo-American eugenics to National Socialist Rassentheorie,”5 Sekula provides a detailed history for Galton’s achievement in a fascinating footnote, too lengthy to quote here in full. It narrates the process whereby Galton would assemble young Jewish students in London, placing the negatives of their photo-portraits one on top of the other, then printing a single average portrait of the “pure racial type of modern Jew.” The result served, as we read in a 1885 review, two opposite ideas: While Galton opted for the conclusive representation of “the Jew as the embodiment of capital,” with particular attention to the Jewish “cold scanning gaze,” others found those composites to be “more spiritual than spirit,” as they bear traces of biblical forefathers—Samuel the Prophet and King David—thus buttressing a “proto-Zionist myth of origins.”6

Reading these lines in class, we make a point to situate Sekula’s investigation in photography history not only in retro-spection on Nazi eugenics and its anti-Semitic precedents but also in pro-spection of the common denominators for Galton’s system and the thriving security industry in contemporary Israel—a relentlessly productive and profitable enterprise of the past two decades where hi-tech innovation joins hands with nationalist xenophobia, military control (here as elsewhere), and constant occupation of the field of vision.7 This bidirectional perspective allows us to read “The Body and the Archive” not as photography history alone but as a creative space for negotiating the instruments of maintaining identity and difference across the “authoritarian turn,” whereby Israel’s obsessions with surveillance essentially stem from the maintenance of the Zionist framework for the current regime in Israel/Palestine.8

These breaches are made possible to track thanks to the spatial and temporal leaps from Sekula’s historical subjects to us, now, on Mount Scopus, where—as at many other college campuses here and elsewhere—cameras monitoring social conduct are designed to remain maximally hidden, while the monitored community is of the generation most occupied with seeking visibility (often already steered by “imagined surveillance” on social media).9 In particular, Sekula’s essay emphasizes the human face as the site for the production, reproduction, and abduction of human identity, and we are reading his essay when this site of the face is willingly manipulated according to ever-changing fashions of computer-generated algorithms of desire and mass consumption. Lips, cheekbones, and eyebrows look increasingly similar in increasingly younger ages, whether in the context of greater versions of face and body transformation or not, and I cannot ignore this fact when speaking in front of the students facing me. These reflections, however ethnographically esoteric, will become central to the comparative analysis of two contemporary artworks in the second section below, two cases where social conventions of identification are challenged by photographic means in order to illuminate the matrix of legitimizing and delegitimizing certain groups according to ethnic, economic, and gender categories. The classroom, as well as the museum, will serve here as Arendtian “spaces of appearance,” where we encounter one another and others, albeit under material conditions which “repurpose this appearance and undermine our freedom,” in the words of Laura Wexler.10

While observing the visual history brought up in “The Body and the Archive,” a somewhat unexpected comment was made in class, which seems to me as reflecting the more genuine and potentially critical sense of responsive acknowledgment, of what could we give back to Sekula’s essay. I projected the archival illustrations from Sekula’s piece on the wall, and some of the students said that the photographed faces in the Bertillon cards or Galton composites were rather impressive and strong, that their subjectivity seemed to gain presence rather than being repressed by those historical mechanisms of photographic standardization. That response required a rereading of Sekula’s main argument:

We are confronting, then, a double system: a system of representation capable of functioning both honorifically and repressively . . . . On the one hand, the photographic portrait extends . . . a traditional function . . . of providing for the ceremonial presentation of the bourgeois self. Photography subverted the privileges inherent in portraiture, but without any more extensive leveling of social relationships, these privileges could be reconstructed on a new basis. That is, photography could be assigned a proper role within a new hierarchy of taste. Honorific conventions were thus able to proliferate downward. At the same time, photographic portraiture began to perform a role . . . [which] derived, not from any honorific portrait tradition, but from the imperatives of medical and anatomical illustration. Thus photography came to establish and delimit the terrain of the other, to define both the generalized look—the typology—and the contingent instance—of deviance and social pathology.11

Countering Sekula’s social critique, the students’ response to the images was telling. I considered that response typical of a generation whose constant exposure to photographed faces through different platforms, over global distances, and in accelerating pace is so immensely far from those that shaped visual conception for both Sekula and Galton. Yet, it was a great moment of joint reflection on the fact that Sekula, indeed, does not develop that honorific side of his phenomenological-historical formula. “The Body and the Archive” does not acknowledge the identity of the photographed subject and does not discuss the “honorific conventions” in the photographic production of Bertillon’s and Galton’s systems; instead, the author awards that potential to the work of independent documentarists who break away from archival logics altogether, as will be discussed below.

The issue of individual identity is key to the very distinction between the Bertillonage and Galtonage methods: While the former rests its entire archival logic on access to the detailed identity card (which includes full name and place of birth, among other data), the latter seeks its authority from the very effacement of those particular details. Moreover, when looking today at the products of these archival machines (just as Sekula did in his research), one may still be interested in who the photographed subjects are. Prior to the sociohistorical scaling-up of one portrait from an institutional archive to whichever society it represents, viewers may be curious to know something about that person who was often involuntarily put in front of a camera lens, subjected to what Tina M. Campt termed a “quiet and quotidian” genre of images.12 If the investigated visual resource provides no clear (visible or “audible,” following Campt’s more sensitive model) answer about that identity, if it fails to fulfill the ordinary expectation from most photographed faces in our time, then we are called to reread Sekula’s text more reflectively: How exactly can we acknowledge the person we see in a photograph under the forces inflicted upon our society by the mechanism of the archive? What else can we do when in investigating a photographic archive, we face people we do not and cannot know but we nonetheless feel we should?

Leaving aside the explanation for Sekula’s preference of the “repressive” over the “honorific” act of the camera,13 the comment in class was an opportunity to rethink the power of the photographed face over its viewer, even when that face is unidentified, even when that face is a product of utter fabrication. The turn from somebody to anybody, which is key to understanding Sekula’s historical exploration, is left unchallenged by an opposite turn. This problem has only grown, I believe, with the “archive impulse” in the arts, which Hal Foster identified at the turn of the millennium—a reappearing tendency in photographic manifestations to which the artist Allan Sekula contributed some early and significant harbingers.14

The honorific perspective is not just an outcome of the planned design of a photographic portrait but a critical possibility which may be applied by later viewers of that portrait. Consequently, this is a potentiality resting inside archives which may play a reconstructive role, as John Tagg reminds us:

In the space of the archive, therefore, the politics of truth inevitably folds into a politics of identity through the regulation of relationships both to time, truth, and memory and to the practices and technologies of record and recollection. As a result, while the archive may once have seemed destined for invisibility in the anonymity of its functioning, the forces of self-determination, decolonization, and their counter-movements have made it a highly politicized space, as communities have come to be seen as being made and remade through the sharing of the ethical obligation of remembrance and through the claim to “collective memory,” of which the archive is now seen as the repository.15

Rereading Sekula with Japan and Yemen

Conceptual art, especially under institutional-critique agendas of the past sixty years (and prior to the “archival turn” of the late 1990s), has been embracing the archive as both medium and idea.16 Numerous artworks, exhibitions, reviews, and academic publications have emphasized the key role of the found photograph in that trend, as it has provided artists with the visual vehicle which merges evidence with aesthetic manipulation and critical reframing of that evidence. Photographic materials—whether extracted by the artist from existing, albeit unnoticed repositories, or created by the artist to cover unnoticed phenomenon—conveyed on various art stages a certain kind of exposure that in most cases suggested an alternative truth. Art that counters the archive by turning it aesthetically rewarding, as if it would change its essential ontological status, still occupies much space in the arenas of contemporary art, and it often still aspires to enjoy that power of corrective historical narration.17

While Sekula concludes “The Body and the Archive” with linking the history of photographic archives to the evolution of photography as an independent art form, the more recent artistic exploitations of archival materials and settings have further complicated the relations of camera-actions and truth-telling. Commenting on the use of archives artistically (a comment that sounds, in retrospect, self-doubting), Sekula writes in a later text:

Any photographic archive, no matter how small, appeals indirectly to [different] institutions for its authority. Not only the truths, but also the pleasures of photographic archives are linked to those enjoyed in these other sites. As for the truths, their philosophical basis lies in an aggressive empiricism, bent on achieving a universal inventory of appearance. Archival projects typically manifest a compulsive desire for completeness, a faith in an ultimate coherence imposed by the sheer quantity of acquisitions. In practice, knowledge of this sort can only be organized according to bureaucratic means.18

I shared with my class two different artworks which may help us understand the incorporation and manipulation of those “bureaucratic means” in artists’ current photographic practices. We found the distinction Sekula made between Galton and Bertillon—“two poles of positivist attempts to regulate social deviance by means of photography [and] the two poles of these attempts to regulate the semantic traffic in photographs”19—resonating in the differences between the work of Japanese artist Tomoko Sawada (b. 1977) and the work of New York–based Israeli artist Shabtai Pinchevsky (b. 1986). Both exemplify the trickling down and perpetuation of the “archival impulse”; however, departing from Foster’s and Sarah Callahan’s art historical diagnosis, Sawada and Pinchevsky also exemplify a critical deconstruction which can be achieved once the archive is in the hands of artists who were subjected in one way or another to its repressive consequences, while having some firsthand technical experience in the making of archives, in serving among its unacknowledged manpower.

In 2015, Sawada presented at MEM Gallery, Tokyo, a grid of three hundred 8½-by-11-inch framed photographs, each presenting the artist’s face differently: Her hair and makeup, as well as the position of her head and facial expression, change according to visual stereotypes of ethnic identities by which the artist was incorrectly perceived by others (strangers and friends alike) once she moved from Japan to the US. “Quite often, when I lived in New York City for six years, I was perceived as being of Chinese or Korean or Singaporean origin . . . only occasionally Japanese,” Sawada said in an interview for the presentation of this project at ROSEGALLERY in Santa Monica the following year. “This made me consider the intuitive process by which people achieve cognition of true or false archetypes. The experience led me to create this new project, transforming myself 300 times to look like a variety of East Asian Women.”20 In Facial Signature, this photographic confrontation—facing the lens and the viewers collectively, albeit in a fabricated manner—crystalized as a new, bolder, and yet more rigid formula: Viewers encounter the critique of institutional and social identification processes as a sheer confusion, the number of female faces looking at you is nearly uncountable, impossible to tell the difference between them, even when it is so visually clear. The most immediate connotation of difference available is that of racial origin, but it is hard to tell whether that connotation is due to the mostly Western blindness of visual differences among facial features of various Asian ethnicities or due to the global blindness to identity disseminated through the mug shot.

An edition of Sawada’s Facial Signature was acquired by the Israel Museum in Jerusalem and temporarily displayed at its East Asian Arts galleries. As its curator, a common question I encountered upon guiding visitors in this exhibition was, “So who is Sawada among all these faces?” Taken seriously, this question reflects the very contradiction conventionally posed between multiplicity and individuality, fueled by the deeply entrenched institutional desire to demarcate and augment the unique genius and identity of the artist (a popular desire which Sekula considered part and parcel of the Romantic “cult of private experience” with art).21 Moreover, that search for the “real Sawada” among the seemingly repetitious photography installation reflects the general impression of realist representation which such archival art enjoys. These modernist conventions—the singling of the genius artist and the embrace of archival staging of realism—together link the incapability of sensing difference among numerous East Asian faces back to that same “deficiency” in telling people’s identity in such a race-obsessed society as contemporary Israel. Indication of differences within a multitude of apparently similar faces becomes a social neurosis when basic visual likenesses thwart regulations of nationalist demographic control, like the one between Jews and non-Jews in Israel.22 The historical context of that social neurosis and its relation to the existential issues at the basis of Zionism aside, Facial Signature seems to provide a much wider, transnational framing for these same cultural preoccupations.

Sawada fools us, and quantity is her key: She cannot “be found” in this massive grid of portraits, simply because she assimilated the photographer with the photographed subject in a way that proves how identity can never be “found,” only founded, made-up (the term “foundation” in the makeup industry comes to mind). In Sekula’s long-term lexicon, Sawada would first be the laborer of her own struggle against the machinations of identity construction in the age of globalized mass reproduction. The artist employs here her previous occupational experience as a television makeup artist, where broadcasters’ cameras with all the surrounding professionals produce personas in the service of given social scripts. Every detail is important for the construction of a photogenic, teleportable character: the light under the chin, the glow and tone of haircut, the angle of eyelashes. Each detail, combined with others, may connote another ethnic or socioeconomic group, but when this entire code is handled by the insurgent artist, even viewers most familiar with the culture tensions on display may get lost. In principal, the making up of these plethora of different faces is nothing less than a work against the “original language of Nature, written on the face of Man,” as John Caspar Lavatar defined the “science of physiognomy” in the 1770s.23 Sawada’s fabricated bank of Asian women insists, however, on racial mapping more than on allotting mental or behavioral characteristics to physical features of the skull or the face; these would have been assumed by an already racially distressed society of observers. We, the audience at the Israel Museum, play the role of the paranoid policeman or criminologist in Sekula’s account.

Yet, in reading “The Body and the Archive” today, we carefully pay attention to Sawada’s title. Facial Signature is a term taken from one of the most advanced and controversial technologies of control in the past couple of decades: borders, markets, communication systems, anything whose operation depends upon the penetration of the public for sorting out and canceling any interruption in its docile economic behavior. Facial recognition systems today are mostly based on artificial intelligence software which scans videos and images that show an individual’s face to create a map of his/her facial features called “a facial signature.” This includes data like their eyes’ precise location, scars, moles, or other facial differences. Then, the software compares the individual’s facial signature to its database—today based on various commercial and governmental datasets hoarding billions of images—and records the matchings. In the words of Nikki Stevens and Os Keyes, “Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) is not a single technology but an umbrella term for a set of technologies that provide the ability to match an unknown face to a known face.”24 This last phrase is helpful in exploring the aesthetic experience in front of Sawada’s photography installation, where numerous faces unknown to the inquisitive viewers only amplify the discomforting realization of their own facial anonymity and visual deficiencies. Significantly, Sawada imports into the encounter with contemporary art the language and logic of rationalist visual presentation whose primary target is making all things known—not so far from the encyclopedic rationale of such Western ideological apparatuses as the Israel Museum. One had only to look around the geographically ordered ethnographic collection of the East Asian art galleries, and then look up in search of the routinely operating security cameras.

The rationale of facial identification systems goes back, according to Sekula, to the Belgian statistician Adolphe Quetelet, whose “average man” idea inspired both Galton and Bertillon. Preceding the invention of FRT by roughly two centuries, Quetelet’s 1835 treatise “Sur l’homme” (A treatise on man) reads: “The greater the number of individuals observed, the more do individual peculiarities, whether physical or moral, become effaced, and leave in a prominent point of view the general facts, by virtue of which society exists and is preserved.”25 This politicized scientific reasoning streams through the first dataset of human faces assembled for computer-based facial recognition. The CIA funded the Bledsoe system developed in 1963: an archive of photographic portraits of white men (in suits) with applied coordinates by which computers can locate certain facial features (similar to the anthropometric systems explored by Sekula). Looking again at Sawada’s meticulous yet conservative foundation of her own data, it is of essence that the early Bledsoe system—just like those of Galton and Bertillon—was not a simple collection of given mugshots but a bank of carefully, newly made studio portraits against a black backdrop: “Beyond their control of photographic conditions, the Bledsoe team did not perform computational interventions to standardize their subjects or their photographs; they simply chose subjects who fit standardized profiles.”26

While the constantly developing technology of facial recognition has been raising many arguments against its dangerous inaccuracy or privacy and property violations, two characteristics are especially relevant in considering Sawada’s acute title: First, facial recognition has proven to be less successful in identifying women and people of color (a racial and gender bias that goes back to the building of early FRT datasets that used only middle class white men)27; and, second, it could still be tricked, even in the most camera-secured public spaces, by wearing certain kinds of makeup.28 Sawada brilliantly merged in a single act the exploitation of these two technological flaws. She turns back to the complicated notions of mask and masking in her culture of origin:

In creating my work, I never try to become someone else or make reference to a particular individual. I simply try to make myself look different. And in order to do that, I change my appearance. But I never empathize with, or act as, someone else in my photos . . . . In Japanese, the words kamen and omen would both translate into English as “mask,” but they imply different things. Wearing a kamen conceals one’s true form, and there is no need to act. But when you wear an omen, the assumption is that you play the associated role. My work deals with kamen, but many people who see my photographs seem to think I’m performing, which I am not.29

Sawada’s work follows the promise and praxis of the nineteenth-century anthropometrics surveyors, as well as the twentieth-century security programmers, leading us into the current state of all-encompassing surveillance society, but she discloses the one component they all work hard to conceal: truth-telling. Facial Signature is an archive that reveals only its controlling creator, along with admitting that photographic portraits in archives can only lead you away from knowing a person.

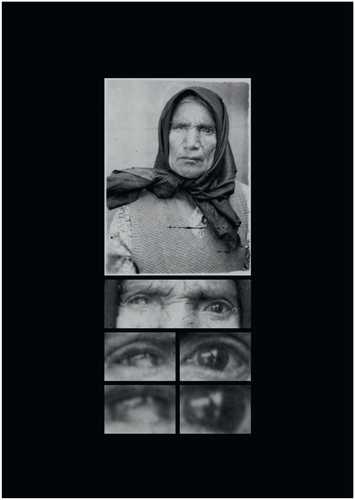

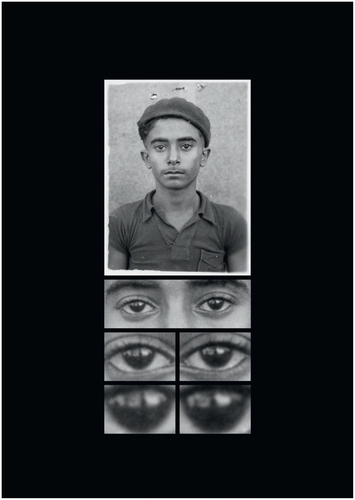

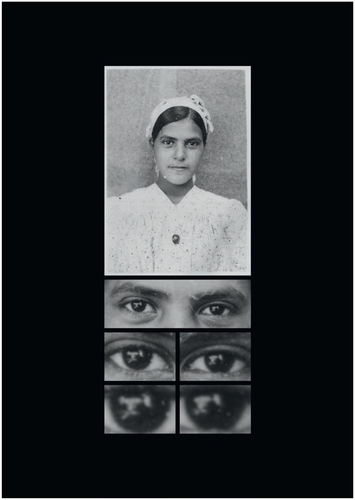

Sekula reminds us that “the archive is both an abstract paradigmatic entity and a concrete institution. In both senses, the archive is a vast substitution set, providing for a relation of general equivalence between images.”30 In other words, the actual space of an archive and the structure of information held in it serve the rationale of universal truth based on comparisons: the more, the better. Comparing things, in the empiricist tradition, gets easier the finer one dissects the investigated object to a greater number of particles. From the Shoe Box is a 2015 series of photographic charts made of scanned materials which Shabtai Pinchevsky found in the archives of the Yad Ben Zvi Institute in Jerusalem—a research institute and archive founded in 1947 to explore the history of Jewish communities living in Arab countries. Pinchevsky was then an intern whose job was to scan visual artifacts in the collection and was told by his employers that “that shoebox over there is nothing but a waste of time.”31 After a while, when left alone at the archive, he returned to that box. Inside, he found hundreds of passport-size portraits of Yemenite “ascenders” (olim, Jewish immigrants to Ottoman/British Mandate Palestine, later Israel). Many of them, so he recalls, were “staring back at me with an angry look. That look felt strangely justified.”32

Pinchevsky scanned the entire content of the neglected shoebox—indeed, doing the filing job that the archive essentially failed to do. The high resolution of the scan allowed him to playfully zoom in, enlarge the image on screen, frame only the glaring gaze of each portrait, then closer on the eyes, and even yet closer on those shiny black irises. Each step is then extracted and placed separately into a diagram of sorts, where the original identification photograph is fully displayed at the top and the strange couple of dark marbles are at the bottom. The final printed work, rather modest in size, is arresting. The quick, intuitive move of my look from the top full figure to those staggering singled-out eyeballs nearly shuts off any intellectual investment, such as asking, naturally, who that person is: I must first struggle with the feeling of being watched by printed matter.33

The artist testifies that it is the monotonous sedentary labor for endless hours in the archive where many of his artworks begin. According to Pinchevsky, every single action in the long and complicated process of digitization of visual archives is complicit with the maintenance of certain narratives. This entails not simply what is eventually collected, selected for scanning, storing, recording, backing up, and so forth; historical knowledge is also made by the level of scanning resolution, the digital weight of files, the saving of memory space on a certain server. When Pinchevsky maximized zooming-in on those dark eyes of the Yemenite ascenders, it was the realization of a technical potential, initially enabled, but eventually limited, by the ordinary decisions and minor actions of the intern in the archive—this time, an intern fully aware of their political implications.

Pinchevsky continued to explore the story of that shoebox: After decades of illegal and individually organized Jewish migration to British Mandate Palestine, the first organized transportation of Jewish Yemenite immigrants to the newborn state of Israel departed from Hashed Camp, outside the city of Aden. Titled “On the Wings of Eagles,” the first round of that operation brought to Israel 5,500 Jewish refugees from Hashed Camp some years earlier. Responding to the rise of anti-Semitism in Yemen during the 1940s, eventually the operation brought to Israel more than 50,000 Yemenite Jews. When those pictures were taken, as Pinchevsky reports, the camp “was in a humanitarian crisis. Overpopulated, with spreading diseases, disregarded by its staff and with a few members violently expelled over religious feuds.”34 For the artist, the demanding gaze of the photographed poor immigrants was not just the result of their hardships at the refugee camp nor the anxiety before departing on a plane to their religiously imagined Zion. Those angry eyes foresaw the failure of that “ascending”: Their belongings taken away, they will soon be placed in transit camps in Israel (Ma’abarot), mixed with Jewish immigrants from other Arab and Eastern European countries, and the scars from those sociopolitical shortcomings will have impacted internal tensions in Israel up to the very present.

Shabtai Pinchevsky, From the Shoebox: The Picture of Zohara Yosef Gridi, 14/1/49, Yechiel Shlomo Kessar, 2015, digital print (artwork © Shabtai Pinchevsky; photograph provided the artist)

Shabtai Pinchevsky, From the Shoebox: The Picture of Said Salam Hassan Habani, 9/1/49, Yechiel Shlomo Kessar, 2015, digital print (artwork © Shabtai Pinchevsky; photograph provided by the artist)

More questions piled up as Pinchevsky shifted archivist routines artistically. Zooming in on the Yemenite refugees’ eyes, the artist discovered the reflection of the photographer. A surprising presence, across time and space, of a trace from that rather forgotten history. The photographer was Yechiel Shlomo Kessar, who worked for the Jewish Agency in Aden. His name appeared on some of the photographs Pinchevsky scanned, and the two photographic activities became closer—indoors digital scanning now and outdoors analog portraiture then:

While scanning and cataloguing, I came upon another familiar name. Haim Madala and Yona Madala, carrying the same family name as my grandmother’s maiden name. At her house, there was a framed composition of the patriarchs of the Madala family. I used to be fascinated by it when I was a small child, and in it, I find Haim and Yona, older by a few decades. I contacted their relatives, and discover that Haim and Yona are already deceased.

I finished the scanning and cataloguing process. All the leads ran their courses. The project was put aside for now, completed. Then my grandmother passed, and the funeral and the week-long mourning at her house was surprisingly flooded by unfamiliar faces. They were all friends of my uncle, Shalom, a religious man who, at a young age, became a follower of Rabbi Uzi Meshulam and a member of his community. In 1994, Meshulam and a few of his followers, my uncle not included, barricaded in a house for weeks, with stones, sandbags and weapons, demanding an official inquiry to their claim—that during the 1950s, Israeli officials and different agencies were engaged in kidnapping and human trafficking thousands of Yemenite newborn babies and children. These claims were eventually investigated by numerous public inquiries, which failed to give convincing and confident answers.35

In our class on Sekula’s essay, we observe Pinchevsky’s fragmented photographic portraits, confronting those demanding eyes, as they inflict a certain reflection on the history of designing identities in Israel by the force of erasure. Some students said that the dismembering of the photographed face—in a way, against the enlightened ideal of the dominion of the head and the mind to which Sekula responds—somehow makes those scanned portraits less generic and more memorable. Thus was the artist’s response to that powerful gaze, and he found himself absorbed by those eyes, thus resonating his biographical connection to Kessar and to what was lurking behind those images for years. This dynamic of visual-psychological dissection is already different from Bertillon’s method of facial fragmentation; while Bertillon is interested in sorting and signaling various facial organs (especially the ears), Pinchevsky is interested only in the eyes, and then in turning them indecipherable, incomparable, scientifically useless. Unlike Sawada, the way Pinchevsky deals with masses of visual items is not by displaying multitude but rather by inventing a new filing format, one that counters archival doctrines. Yet, in both Sawada’s and Pinchevsky’s works, the resulting print of a single face is relatively small (especially in contrast to the convention of large printing in contemporary photography and its spaces of display), which is a significant choice for resetting an aesthetic experience where comparative view is easily available.36

The magnifying scanning also discovered that in some portraits the eyes did not reflect the photographer since the irises turned white due to an eye disease in the Hashed camp—an ominous blindness on both sides of this history, of the 1948 Yemenite refugees, on the one hand, and Pinchesky’s 2015 inability to “catch” the photographer, on the other. Some works in the series From the Shoebox show those blurry pair of eyes, while other photographed gazes display clearer vision, more comfortably equated with the one who views them today. Yet, in all of the prints, the visual arrangement starts with that involuntarily taken portrait—the most generic use of cameras throughout the history of the medium—and ends with those two round shapes which lead the viewer away from the recognizably human and closer to the photomechanical, like camera lenses capturing whatever stands before them. The photographed portrait is fragmented in a visual hierarchy where the bottom line is taken literally to mean a conclusion. As an exercise in deduction, the subtraction of the face to eyes only—that is, to the role of sight and the sense of vision—Pinchevsky’s Bertillonage seems to have a surprising summation: Instead of indicating traces of identity or reading personal qualities inscribed on distinct facial sections of the subject, it lends itself to mirror both the photographing and the viewing agents. Instead of “eroding the uniqueness of the self”37 through a massive text-and-image mechanism of comparative identification, Pinchevsky’s photocollages seem to seek the restoration of the individual, primarily the photographer and the viewer.

The standardized composition imposed on the photographed Yemenite is partly congruent with the visual standardization of the camera and the archive. The story of collective erasure from national memory behind this standardization, however, stretches from the very act of taking those photographs in Yemen to the act of storing and digitizing them in Jerusalem half a century later. Pinchevsky (just like that cameraman “captured” in eyeballs from Yemen) is somehow implicated in both moments: Each one of his found portrait collages is given a title with the name of the photographed person and the name of the photographer. It is a slight yet radical conceptual intervention in the traditions of portraiture. Let us take a closer look, for instance, at the label of the work shown above: Shabtai Pinchevsky, From the Shoebox: The Picture of Said Salam Hassan Habani, 9/1/49, Yechiel Shlomo Kessar, 2015, digital print. This label incorporates two different photographic events and three different actors in those events, crossing technological developments, sites of identity formation, and significantly separate ethnic affiliations associated with certain family names (“Pinchevsky” is East-European, “Habani” Arab). In such condensed appropriation—where the work of art “tells” us it is “a picture”—the entire system of standardized data turns the archive into a conceptual, albeit ideological statement accompanying a single visual object which is now newly individualized.

This act of singling out, of turning a serial item into a memorable, powerfully looking character, seems to derive from the realization of personal connection between the artist and the archive. Pinchevsky’s personal involvement—his testimony which ties his work in the Yad Ben Zvi archive to his family relation with the national trauma of the kidnapped Yemen Children (analogous to Sawada’s personal involvement in the story of racial stigmatization in postcolonial landscapes)—is a generator for undoing the archive logic. The zooming in on those black irises, the stories they suddenly reveal, turns them from cataloged items in another historical repository to general statements on historical blindness. This shift is achieved by a particular design which—unlike Sawada’s equalizing texture of innumerable similarities—suggests a certain quality of what Sakula calls “social leveling and decline” when indicating the essential difference between the photo-archival methods of Galton and Bertillon.38 Bringing the works of Pinchevski and Sawada to our class on “The Body and the Archive” anchored the relation of these two different contemporary artworks to the “age of surveillance” and to potential breaches that artists can still open for us within such social conventions. Decades after Sekula’s socioaesthetic observations and Foucault’s conclusions on panopticism, surveillance can now be considered not as an instrumental monitoring of the modern self but rather as a quality of every act of every camera, overt or covert. When it is in the hands of artists like Pinchevsky and Sawada, such an omnipresent apparatus starts to break, to operate against its design, while opening new avenues of aesthetic interpretation.

The issues that bothered Sekula in critically exploring the impact of the camera-based rationale of the archive—comprehending the meaning of masses of people in masses of images or the long-degrading trust in the existence of consistent identities between authentic and fake—still occupy the art of Sawada and Pinchevsky, as well as many other camera artists of their generation. While both play with exploiting the modern machinations of the construction and distribution of racial stereotypes, their creative stimulus seems to derive from the inflection of contemporary camera-ruled anthropometrical mechanisms upon the artists themselves—Sawada with her own performance incongruent with Western stereotypes of Asian women, Pinchevsky with his family ties to an unspoken, undocumented state-run campaigns of Westernizing socialization. “The Body and the Archive” overlooks the possibility that Bertillon could be himself the subject of Bertillonage or that Galton could quite probably look like one of his own composites. There should be no reason for Sekula to consider this, as Bertillon and Galton were not criminals, certainly not in their own eyes. Nonetheless, Sekula concludes his essay by considering every photographic act of documentation complicit in the same system from which the artist aspires to dissociate; there opens the possibility to see artists themselves as both victims and operators of the same camera-ruled system of signification. Sekula presents the 1960s street documentary of South African photographer Ernest Cole as a transgressive move against that same system, which restores the humanity of a racially criminalized Black society. Sawada and Pinchevsky, however differently, seem to aspire to parallel possibilities for that insurgent counterarchival stance: Sawada employs her “self” instead of a repository of “other-referents,” while Pinchevsky employs gradual abstraction of the face instead of instrumentally rendering the human face informative. Sawada and Pinchevsky seek after themselves in the conventionally documented multitudes they map, not to reach their own fixed identity but rather what its absence critically represents. In the semiotic lexicon Sekula borrows from Charles Sanders Pierce, we could say that both artists move away from “the indexical order of meaning,” treating the photograph not as “a physical trace of its contingent instance” but rather as a symbol, “expressing a general law through the accretion of contingent instances.”39

We read “The Body and the Archive” in class and analyze artworks from the past decade, and by this we acknowledge and reactivate the essay’s significance to the present moment. At the same time, the artworks we analyze seem to be grounded in ideas which have concerned human societies for many generations; that is, they belong to much longer and diverse timelines than what we conventionally deem as contemporary. The tribute, then, seems to go both ways: The photographed face is acknowledged just as the old text is; looking back at it is always rewarded by another, reflecting gaze. And beyond this theoretical-pedagogic formula, there is the impact of a face looking at me from across great temporal, spatial, and modal distances, beyond and against the neutralizing and oppressive structures of the archive, where the honorific register of any photographed person is not canceled once and for all but rather lies in anticipation of artistic interventions, as it carries some aesthetic potentiality initiated by one camera act.

Dr. Noam Gal teaches in the Art History Department at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His main exhibition projects have featured Richard Avedon, Yael Bartana, Berenice Abbott, Chen Cohen, and Micha Bar-Am. His new book The Movers: Israeli Art in the Third Millennium is forthcoming in 2025 (McGill-Queen’s University Press) [Art History Department, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, noam.gal1@mail.huji.ac.il].

- Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” was first published in October 39 (Winter 1986): 3–64. All of my citations from this essay will refer to its republication in Richard Bolton, ed., The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography (MIT Press, 1989), 343–89. ↩

- Allan Sekula, Photography Against the Grain: Essays and Photo Works, 1973–1983 (Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1984), xiv. See also Benjamin J. Young, “Arresting Figures,” Grey Room 55 (Spring 2014): 78–115. ↩

- Cited in Laura Trafí-Prats, “Art Historical Appropriation in a Visual Culture-Based Art Education,” Studies in Art Education 50, no. 2 (2009): 155. ↩

- Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” 371. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 387. ↩

- It is important to distinguish between Israel’s part in the global industry of automated surveillance (with facial recognition among its leading trends) and the common use of such technologies in monitoring and controlling the lives of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. See Elia Zureik, “Settler Colonialism, Neoliberalism and Cyber Surveillance: The Case of Israel,” Middle East Critique 29, no. 2 (2020): 219–35; see also Rohan Talbot, “Automating Occupation: International Humanitarian and Human Rights Law Implications of the Deployment of Facial Recognition Technologies in the Occupied Palestinian Territory,” International Review of the Red Cross 102, no. 914 (2020): 823–49. For a more general formulation of Israel’s technology of surveillance and how it is manifested in cultural production, see Gil Z. Hochberg, Visual Occupations: Violence and Visibility in a Conflict Zone (Duke University Press, 2015). ↩

- Ariel Handel and Hilla Dayan, “Multilayered Surveillance in Israel/Palestine: Dialectics of Inclusive Exclusion,” Surveillance and Society 15, nos. 3–4 (2017): 471–76. ↩

- For recent accounts on the correlations of university surveillance and students’ self-image, see Lindsay Weinberg, Smart University: Student Surveillance in the Digital Age (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2024); see also Brooke Erin Duffy and Ngai Keung Chan, “‘You Never Really Know Who’s Looking’: Imagined Surveillance Across Social Media Platforms,” New Media and Society 21, no. 1 (2019): 119–38. ↩

- Laura Wexler, “To Burst Asunder: Endurance and the Event of Photography,” in Imagining Everyday Life: Engagements with Vernacular Photography, ed. Tina M. Campt, Marianne Hirsch, Gil Hochberg, and Brian Wallis (Steidl; The Walther Collection, 2020), 135. ↩

- Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” 347 (emphasis in original). ↩

- Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images (Duke University Press, 2017). ↩

- Rereading a passing comment in “The Body and the Archive,” Thomas Keenan argues for the possibility of conceiving the photographic archive beyond its repressive order and against Foucault’s “overly strong distinction between disciplinary and repressive power.” See Keenan, “Counter-Forensics and Photography,” Grey Room 55 (Spring 2014): 58–77, quotation at 69. ↩

- Hal Foster, “An Archival Impulse,” October 110 (Autumn 2004): 3–22. Foster indicated several qualities of that wave of archive art, such as its contradiction between the infinite yet immaterial source of the internet versus the actual, tactile installations of the found information in the eventual gallery space; these qualities, two decades later, are changing again and require our reconsideration. ↩

- John Tagg, “The Archiving Machine; or, The Camera and the Filing Cabinet,” Grey Room 47 (Spring 2012): 32–33. In Tagg’s 1988 book, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (University of Massachusetts Press), a rather wider formulation of the evolution and impact of the archive was presented, in which the domestic and urban spaces are paid as much attention as the juridical and criminological ones. ↩

- For a recent account of the “archival” in the arts—both in the changing practices of contemporary artists and in the theories written about their art, fixing it mainly on still prevalent poststructuralist bases—see Sarah Callahan, Art + Archive: Understanding the Archival Turn in Contemporary Art (Manchester University Press, 2022); and Callahan, “When the Dust Has Settled: What Was the Archival Turn and Is It Still Turning,” Art Journal 83, no. 1 (2024): 74–88. ↩

- An often emphasized event in the evolution of archive art is the 2008 exhibition Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art, curated by the late Okwui Enwezor at the International Center of Photography, New York (January 18–May 4). Enwezor’s installation followed archival conventional settings and was accompanied by an essay heavily based on Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever. Like earlier curatorial practices of information display (such as Lucy Lippard’s exhibitions of the late 1960s), the distinction between the curatorial vision on the one hand and the original practices of the selected artists on the other hand was far from clear. Compare Okwi Enwezor, Archive Fever (Steidl; International Center of Photography, 2008) with Peter Plagens, “557,087: Seattle,” Artforum 8, no. 3 (1969): 53–57. ↩

- Allan Sekula, “Reading an Archive: Photography Between Labor and Capital,” in The Photography Reader, ed. Liz Wells (Routledge, 2003), 446. ↩

- Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” 373. ↩

- va Recinos, “This Photographer Transformed Herself for 300 Self-Portraits,” Vice, February 27, 2016.

At that stage, Sawada was already internationally praised for her self-performative interventions in popular photographic conventions, such as the wedding photograph and the school graduation photograph.[22.The projects OMIAI (2001) and School Days (2004), respectively. Sawada’s performative self-portraits consistently combine the confusing potential of photographic reproduction with the critique of gender roles in Japanese society. See Ayelet Zohar, “Between the Viewfinder and the Lens—a Journey into the Performativity of Self-Presentation, Gender, Race, and Class in Heisei Photography (1989–2019),” Review of Japanese Culture and Society 31 (2019): 9–56. ↩

- Allan Sekula, “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation),” Massachusetts Review 19, no. 4 (Winter 1978): 859. ↩

- Especially volatile is the case of visual proximity of Mizrachi Jews in Israel (whose origins from Arab countries) and Arab non-Jews in Israel and elsewhere. See Henriette Dahan-Kalev and Maya Maor, “Skin Color Stratification in Israel Revisited,” Journal of Levantine Studies 5, no. 1 (Summer 2015): 9–33. ↩

- Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” 348. ↩

- Nikki Stevens and Os Keyes, “Seeing Infrastructure: Race, Facial Recognition and the Politics of Data,” Cultural Studies 35, nos. 4–5 (2021): 834 (emphasis added). ↩

- Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” 355. ↩

- Steven and Keyes, “Seeing Infrastructure,” 837. ↩

- Lila Lee-Morrison, “A Portrait of Facial Recognition: Tracing a History of Statistical Way of Seeing,” Philosophy of Photography 9, no. 2 (2018): 107–30. ↩

- Nitzan Guetta et al., “Dodging Attack Using Crafted Natural Make-Up,” arXiv, September 14, 2021. ↩

- Alasdair Foster, “Tomoko Sawada, The One and The Many,” Talking Pictures: Interviews with Photographers Around the World, February 11, 2023. ↩

- Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” 352. ↩

- Shabtai Pinchevsky, Public lecture at the MFA Program of Art, Theory, Practice, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, November 2019. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Observing a nineteenth-century collection of portraits of South African women, Tina Campt (Listening to Images, 49) writes: “Do their gazes situate them closer to us or place us at a distance? Do they command attention or seek to avoid it instead? These are queries we direct, at least initially, to the eyes, and the looks and gazes they create or appear to disrupt.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. In February 2021, the Israeli government acknowledged for the first time the suffering and grief of Yemenite families whose children were taken away upon their arrival at Israel in the 1950s and offered to compensate their descendants. For an updated account of the “Yemenite Children Affair,” see Yoav Galai and Omri Ben-Yehuda, “The Resolution of Doubts: Towards a Recognition of the Systematic Abduction of Yemenite Children in Israel,” in Post-Conflict Memorialization: Missing Memorials, Absent Bodies, ed. Olivette Otele, Luisa Gandolfo, and Galai (Palgrave McMillan, 2021), 119–49. ↩

- Lee-Morrison, “Portrait of Facial Recognition,” 118; and compare this note on print-size with the case of Thomas Ruff’s Anderes Portraits series explored in Lee-Morrison’s essay. ↩

- Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” 363. ↩

- Ibid., 365. ↩

- Ibid., 374. ↩