Ruth L. Benjamin

Ruth L. Benjamin

“Japanese Painters in America”

Parnassus 7, no. 5 (October 1935): 13–15.

Immigration, transcultural influence, and the role of national origin in the production of art are explored in this 1935 article about Japanese artists working on the East Coast. Ruth Benjamin asks: “What of the Japanese artist of today who comes to America, lives among us, modifies our art, and is himself influenced by Western tradition?” In her assessment, artistic style is largely decoupled from race and ethnic origin as she makes a thoughtful analysis of a dozen or so Japanese artists living on the East Coast—Yasuo Kuniyoshi being the most prominent among them. This article underscores that even in their earliest incarnations, CAA’s publications registered the global in the formation of American art.

—Karin Higa

Alfred H. Barr, Jr.

Alfred H. Barr, Jr.

“Modern Art Makes History, Too”

College Art Journal 1, no. 1 (November 1941): 3–6.

Published in the inaugural issue of College Art Journal, Alfred Barr’s “Modern Art Makes History, Too,” resonates profoundly now, amid the institutionalization of that behemoth, the “contemporary,” and the host of questions such accommodation begets. While it is important to recover the urgency of Barr’s 1941 plea to take seriously the art of one’s time—to study it as modern history, to incorporate it into undergraduate and graduate curricula, and so on—it is equally critical to think through such issues from this side of the modernism that Barr, ever the evangelist, worked so very hard to legitimize. This is necessary reading for any class on twentieth- or twenty-first-century art, for reasons historiographical and prescriptive. As Barr put it, “It is our century: we have made it and we’ve got to study it, understand it, get some joy out of it, master it!”

—Suzanne Hudson

A Committee of the College Art Association

A Committee of the College Art Association

“A Statement on the Place of the History of Art in the Liberal Arts Curriculum”

College Art Journal 3, no. 3 (March 1944): 82–87.

The committee members were Millard Meiss, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Sumner McK. Crosby, Sirarpie Der Nersessian, George Kubler, Rensselaer W. Lee, Ulrich Middeldorf, C. R. Morey, Erwin Panofsky, Stephen Pepper, Chandler R. Post, Agnes Rindge, Paul J. Sachs, Meyer Schapiro, and Clarence H. Ward.

In 1944 fifteen of the most prominent figures in American art history issued an urgent warning against the dangers of “specialization, indifference to ends, [and the] disregard of the emotional and imaginative life.” Penned in the guise of a defense of art history’s place in the liberal-arts curriculum, this remarkable short text and its call for “wisdom, responsibility, and judgment” must have required significant negotiations among its signatories. But it is not hard to imagine the mortification these cultural historians must have shared, given their various personal and professional histories, when faced with the US government’s censorship of international exchange, its sponsorship of a propaganda explosion, and its suspension of habeas corpus, the latter upheld by the Supreme Court in the infamous Korematsu decision just seven months later.

—Judith Rodenbeck

Ray Parker

Ray Parker

“Student, Teacher, Artist”

College Art Journal 13, no. 1 (Fall 1953): 27–30.

His education interrupted by the war, the painter Ray Parker returned to the University of Iowa on the GI Bill, and received his BFA in 1946 and his MFA in 1948. After teaching at the University of Minnesota and what is now the Memphis College of Art, Parker moved to New York in the early 1950s. He taught painting at Hunter College from 1955 until his death in 1990. Written for a symposium convened by the sculptor and University of Iowa educator George Rickey at CAA’s 1953 conference—and featuring, among others, Ad Reinhardt, who spoke on the search for a new academy—Parker’s “Student, Teacher, Artist” is remarkably prescient in its discussion of the role of the visiting artist. It remains, after all these years, one of the most accurate mappings of the relationships among the protagonists named in his title, as those relationships are structured and refracted by roles and ambitions in the art world.

—Howard Singerman

Charles C. Furman

Charles C. Furman

letter to the editor

“Army Crafts Program”

College Art Journal 14, no. 1 (Fall 1954): 61–63.

Written a year after the end the Korean War, this 1954 letter to the editor registers the prominent but largely forgotten role that the military played in supporting American artists and craftspeople during the postwar period, as civilians, soldiers, and veterans. Between World Wars I and II, craft was introduced as a therapeutic method with which to rehabilitate returning war veterans, and the GI Bill enacted after WWII played a crucial role in expanding and professionalizing the college art department. But this particular call for craft instructors abroad prompts a rethinking of artistic collusion in various military campaigns of the United States and the ideal of the American artist as a combination ambassador, therapist, and “citizen of the world.”

—Jenni Sorkin

Robert Jay Wolff

Robert Jay Wolff

“The Great White Way”

Art Journal 20, No. 1 (Fall 1960): 25.

An abstract painter and chair of Brooklyn College’s Department of Design, Robert Jay Wolff is perhaps best-known for firing assistant professor Mark Rothko. Never shy about expressing his opinions, he published this screed against museum installation practice in the first issue of the CAA magazine officially titled Art Journal. Wolff describes the modern museum (presumably MoMA and the Guggenheim) in familiar terms: bright lights, bright walls, noisy architecture, and overbearing curatorial conceits, to the detriment of individual works of art. Curiously reactionary and radical, Wolff’s call for institutional modesty resonates today (the suggested return to small picture lights attached to frames does not). The heartfelt complaint spotlights the great white way with us still, and inspires thoughts of how it might be otherwise.

—Katy Siegel

Edward M. Plunkett, Lawrence Alloway, John Russell, Suzi Gablik, William S. Wilson, Henry Martin, Robert Pincus-Witten, Karen Shaw, Robert Rosenblum, Lucy R. Lippard, Tommy Mew, Toby R. Spiselman

Edward M. Plunkett, Lawrence Alloway, John Russell, Suzi Gablik, William S. Wilson, Henry Martin, Robert Pincus-Witten, Karen Shaw, Robert Rosenblum, Lucy R. Lippard, Tommy Mew, Toby R. Spiselman

“Send Letters, Postcards, Drawings, and Objects . . . The New York School of Correspondence”

Art Journal 36, no. 3 (Spring 1977): 233–41.

Each author is represented by a signed entry.

The artist Ray Johnson, maker of correspondences and connections, and attendant of all things trivial and transitory, is less written about than invoked in this essay by twelve people with twelve distinct voices. The contributors variously summon up reminiscences, insights, opinions, facts, evaluations, poetics, and more reminiscences of the central figure, perhaps the founder, of mail art. Johnson used the US postal system as his distributor, pasted his collages on public walls, and held meetings titled “Nothings.” In the end, this multivoiced essay becomes the very thing Johnson initiated, intuited, and otherwise invented in the late 1950s: a social network.

—Constance DeJong

Lucy R. Lippard

Lucy R. Lippard

“Sweeping Exchanges: The Contribution of Feminism to the Art of the 1970s”

Art Journal 40, nos. 1–2 (Fall–Winter 1980): 362–65.

Lucy Lippard’s essay was commissioned by Irving Sandler for a guest-edited issue of Art Journal on the then-pressing themes of “Modernism, Revisionism, Pluralism, and Post-Modernism.” Other contributors were Kurt Varnedoe on revisionism in nineteenth-century art history, Richard Pommer on postmodern architecture, Kim Levin on the state of art in 1980, and RoseLee Goldberg on performance art. The issue wrapped with the transcript of a roundtable discussion among American members of the International Association of Art Critics. Lippard’s article offers a comprehensive view of the impact of feminism on art after less than a decade of struggle. Typical of her writing, it is at once committed and clear-eyed––in this case, passionately espoused feminist ideals are set within a broadly socialist framework. This pragmatic mix enables her to offer a polemical and perhaps prescient judgment: “Feminism’s greatest contribution to the future of art has probably been precisely its lack of contribution to modernism.”

—Terry Smith

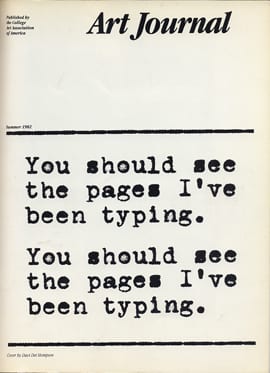

Daniel Buren

Daniel Buren

“Why Write?”

Art Journal 42, no. 2 (Summer 1982): 108–9.

Daniel Buren’s essay appeared in a special issue of Art Journal on “Words and Wordworks.” The guest editor was Clive Phillpot, who at the time directed the Museum of Modern Art’s library and had recently started its Artist Book Collection. Focusing on visual artists who paradoxically produce text-based works, the issue includes contributions by Sol LeWitt, Davi Det Hompson, Iain Baxter, Jenny Holzer, John Baldessari, and Lawrence Weiner—artists who had recently turned to language as an artistic material. Amid this assortment of conceptual wordworks, Buren explains why artists write about art, listing five reasons: necessity, urgency, reflection, commissions, and pleasure. For Buren, artist-writers should claim the critical floor: “The artist isn’t necessarily an idiot or an illiterate—why shouldn’t he write as well?” Buren has faith that the two creative acts can productively parallel and supplement each other, and that the best art withstands the flood of language we throw at it. He calls this art’s “baptism by fire,” a baptism initiated anew with every article and issue we produce.

—Jan Estep

Nelly Richard

Nelly Richard

“Postmodern Disalignments and Realignments of the Center/Periphery”

Art Journal 51, no. 4 (Winter 1992): 57–59.

This snapshot of a fundamental debate in Latin America, from one of the region’s liveliest (if little known in English) voices, points to many of the interconnected issues that were fundamental at the time. Richard’s text is part of an effort to identify what might be useful in the postmodern moment for the reappraisal of longstanding arguments about cultural dependency and—most important—its potential remedies. This sharp-edged and polemical text is an evocative reminder, a couple of decades on, of how high the stakes really were in the fights between postcolonial discourses and the multiculturalisms by which their arguments were so often neutralized.

—Rachel Weiss

Erica Rand

Erica Rand

“Teach Me Today: Finding the Censors in Your Head and in Your Classroom”

Art Journal 55, no. 4 (Winter 1996): 28–33.

Erica Rand’s essay offers a dynamic, first-person account of pedagogical boundaries and the efficacy of sexual politics in the college classroom. Her insistence on student engagement as guided but ultimately self-determined initiates an important dialogue about power, fear, and silence in perceptions of race and sexuality. The essay recalls a feature of this period of the journal’s history: the thematic issue. Guest-edited by Flavia Rando and Jonathan Weinberg, two prominent, longtime members of the Queer Caucus (then the Gay and Lesbian Caucus), the issue was titled, “We’re Here: Gay and Lesbian Presence in Art and Art History.” Such an activist inflection underscores the visceral charge of 1990s identity politics and the hot-button issue of the Culture Wars: censorship.

—Jenni Sorkin

Clifton Meador

Clifton Meador

“Tourist/Refugee”

Art Journal 64, no. 2 (Summer 2005), insert.

In 2005 Art Journal invited four artists to create stand-alone artworks to be enclosed with each copy of the journal. William Pope.L, Clifton Meador, Barbara Bloom, and Mary Lum took wonderfully imaginative and diverse approaches to the NEA-funded commissions. Meador’s 36-page book contemplates a showpiece tourist hotel built in Tbilisi by the Soviet regime in the 1960s. Thirty years later, the skyscraper became a vertical camp for refugees of ethnic cleansing in the Georgian region of Abkhazia. The wrenching photographs, judicious use of sparse text, and above all Meador’s choice to print the piece in duotone with black and metallic silver inks put in the reader’s hands an original artwork not relegated to but rather fully realized in the medium of offset print.

—Joe Hannan

Robin Adèle Greeley, Alejando Anreus, Francisco Alambert, Florencia Bazzano-Nelson, Andrea Giunta, and Holly Barnet-Sanchez

Robin Adèle Greeley, Alejando Anreus, Francisco Alambert, Florencia Bazzano-Nelson, Andrea Giunta, and Holly Barnet-Sanchez

“Forum on Latin American Art Criticism”

Art Journal 64, no. 4 (Winter 2005): 82–93.

Six contemporary writers explore the work of six classic figures in Latin American modernist art criticism, with the aim of sketching the ways that modernity and modernism have unfolded in the region. Francisco Alambert’s “1001 Words for Mário Pedrosa” is especially fascinating for the account of its subject’s trajectory from political militancy into art criticism and then, at the age of eighty, away from art in order to return to strictly political activity—in particular, the founding of Brazil’s Labor Party (which has ruled the country since the election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2002).

—Rachel Weiss