Prefatory note, in the time of COVID-19: When I started this project, it was unimaginable that museums would be shuttered indefinitely and that we would all be in self-isolation, clinging to virtual reality for sporadic shards of normalcy. As I revisited my dialogue with Blake Bradford during the editorial process, it seemed to me that our exchanges in real life, in real space, could serve as a proxy visit to these unique and vital museums and monuments. Blake and I were unable to meet in Montgomery, Alabama, which itself requires some effort to reach from New York City and Philadelphia, and so we began our conversation, which we did not record, on the phone. Blake and I had already (separately) visited the National Museum for African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution (NMAAHC), in Washington, DC, before our respective visits to Montgomery, and so we had the NMAAHC model in mind as the looming point of comparison in the intimate and emotive spaces of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) museum and memorial. Blake and I agreed that the EJI was a powerful testament and indictment of American history, and we wanted to highlight it as a kind of critical counterpoint to the NMAAHC project in Washington, knowing full well that Montgomery would receive a small fraction of the traffic. I begin with a short topographical description of Montgomery and the EJI, which is followed by an edited transcription of the conversations that Blake and I had in Washington, walking through the galleries of NMAAHC. I invite you to come along, think with us, perhaps argue with us, and keep the conversation going.

—Risham Majeed

May 17, 2020

Montgomery, Alabama, and Washington, DC

And the Northern Negro in the South sees, whatever he or anyone else may wish to believe, that his ancestors are both white and black. The white men, flesh of his flesh, hate him for that very reason.

—James Baldwin1

In what relation do we stand to our ancestors if we insist we cannot now even stand to hear or see what they themselves had no choice but to live through? Is not the least we owe the sufferings of the past a full and frank accounting of them?. . . What is the appropriate level of interest in the interrelation of sex and violence in our history?

—Zadie Smith2

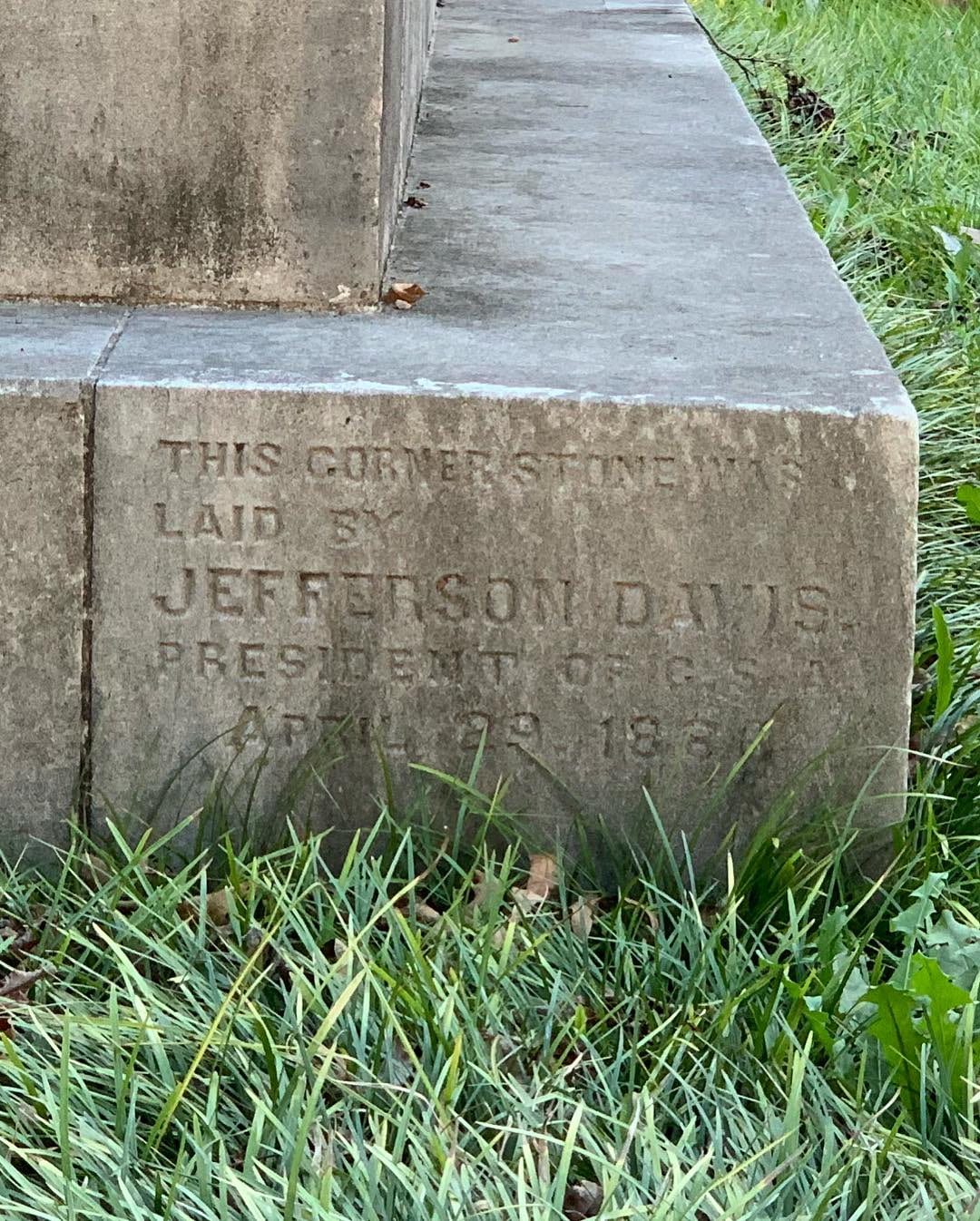

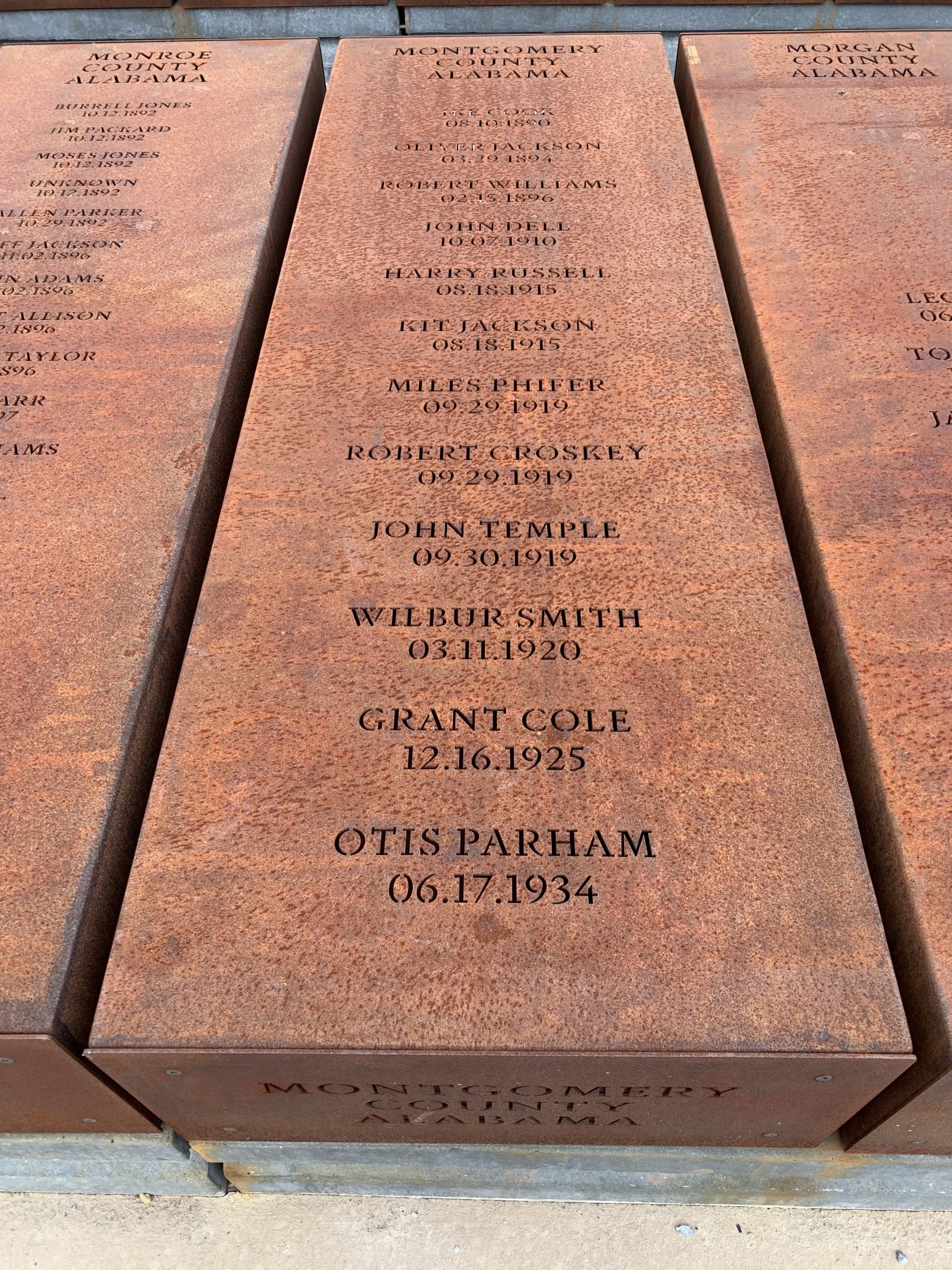

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is situated on a small hill that affords a partial view of the timeless Neoclassical Alabama State Capitol building. While the latter (along with other monuments) presents the official version of the past from the perspective of the Confederacy, with slavery as an almost irrelevant irritant, the EJI memorial and museum fill out that omission, making manifest Baldwin’s observation that black and white have been intimately intertwined from the beginning.

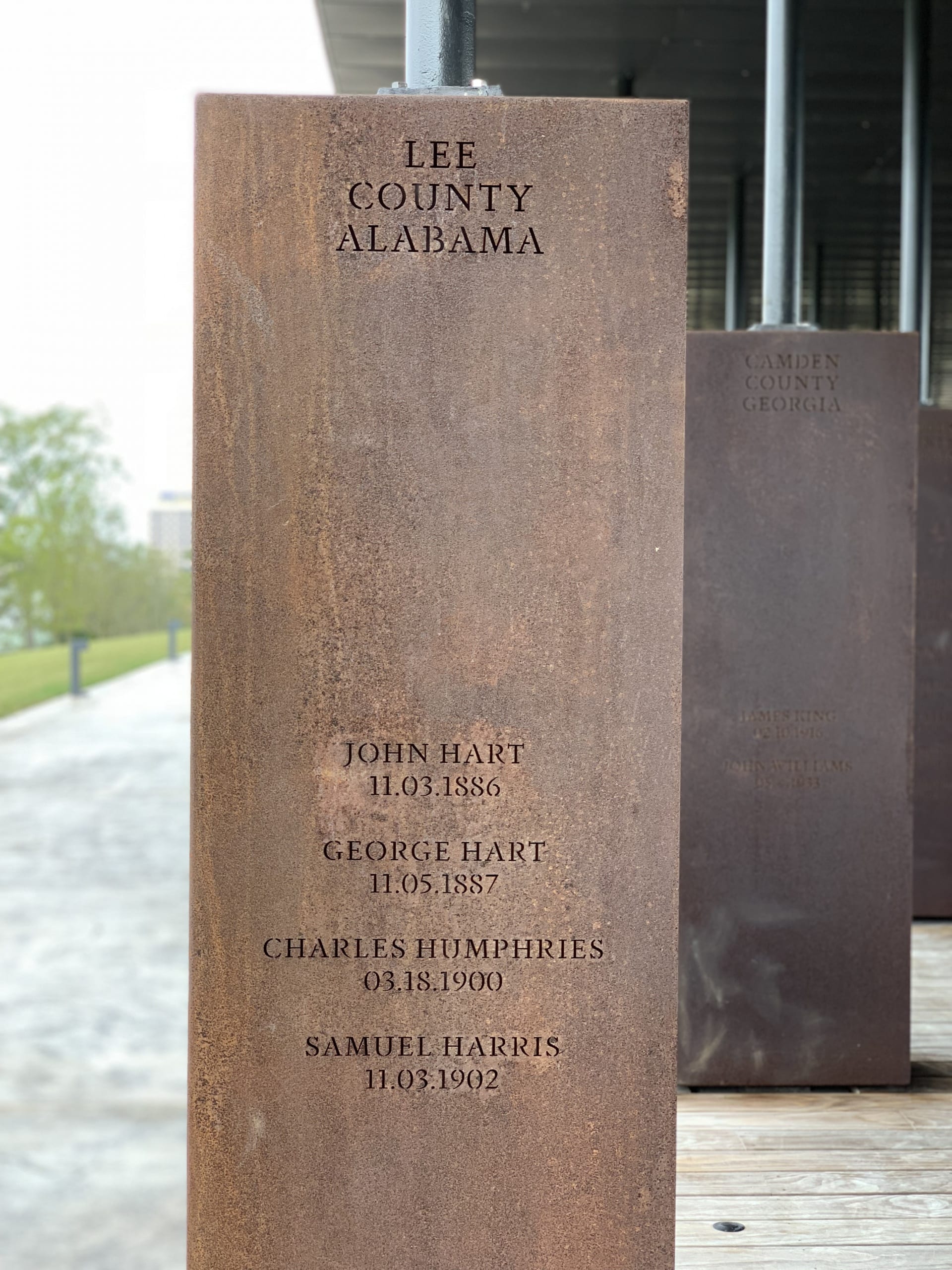

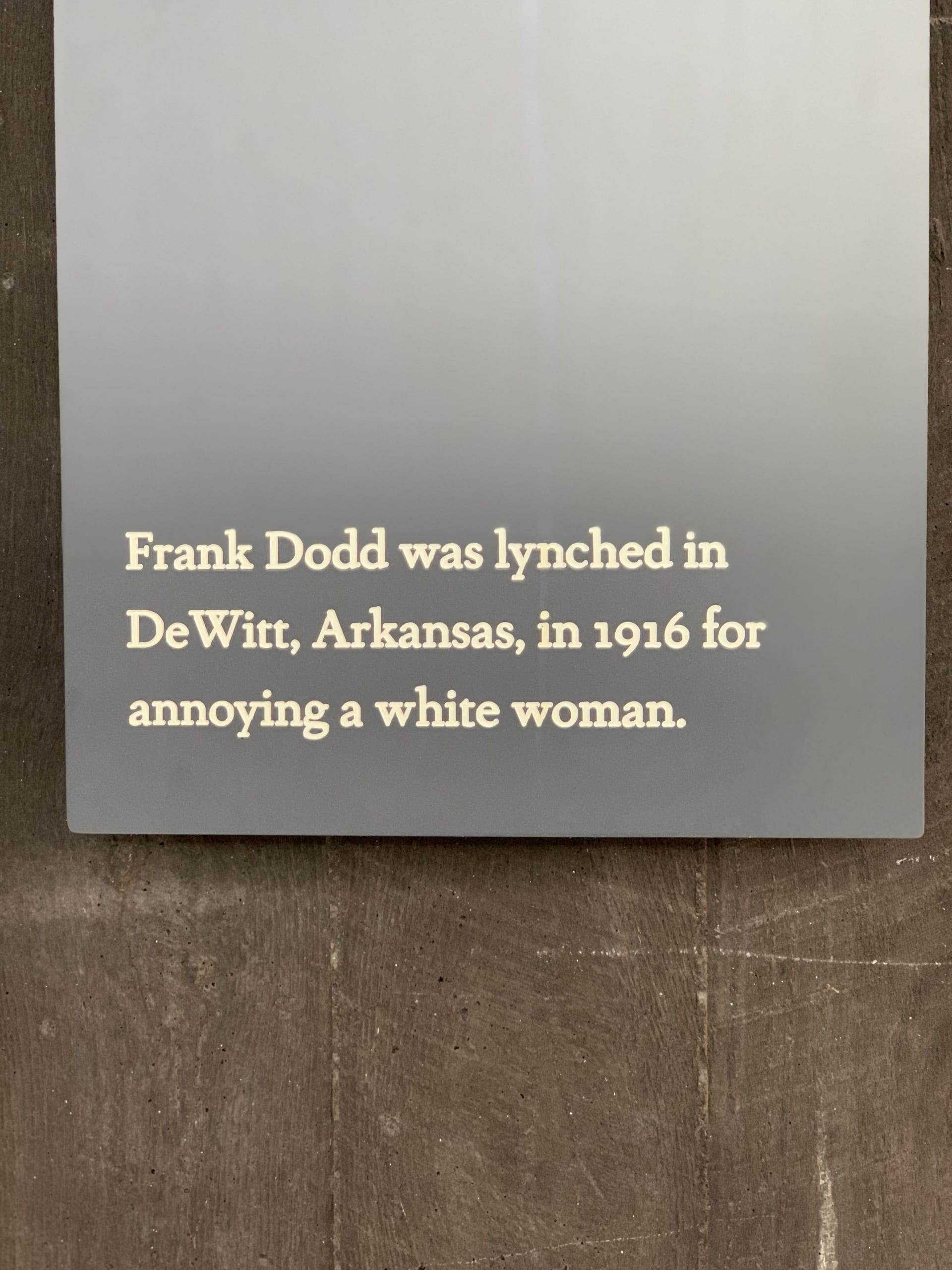

The EJI directly engages the physicality of entwined sex and violence that is foundational to the American narrative: it’s astounding how much of the brutality invoked at the EJI’s lynching memorial was spurred by white men enraged by imagined sex between black men and white women. If the Capitol is as much about the dishonest absence of everyday realities as it is about commemoration, the EJI museum and memorial strives to fill this visual silence.3 Monumentalizing absences, as the memorial downtown does, drops the viewer in the middle of the ongoing tension between white and black in the South.

The memorial’s primary materials are uniform hollow boxes resembling iron, with a patina of rust, which visualize the passage of time through their ongoing surface decay. Iron at once connotes strength and brutality: it is also the material that bound slaves, rendering them powerless. That textured sense of time also returns specificity to ordinary men and women by naming them individually and making their humanity inescapable in the face of the erasure that endures at the Capitol. This productive tension, visually and morally, is effective at EJI and is selectively deployed at NMAAHC, which we discuss below.

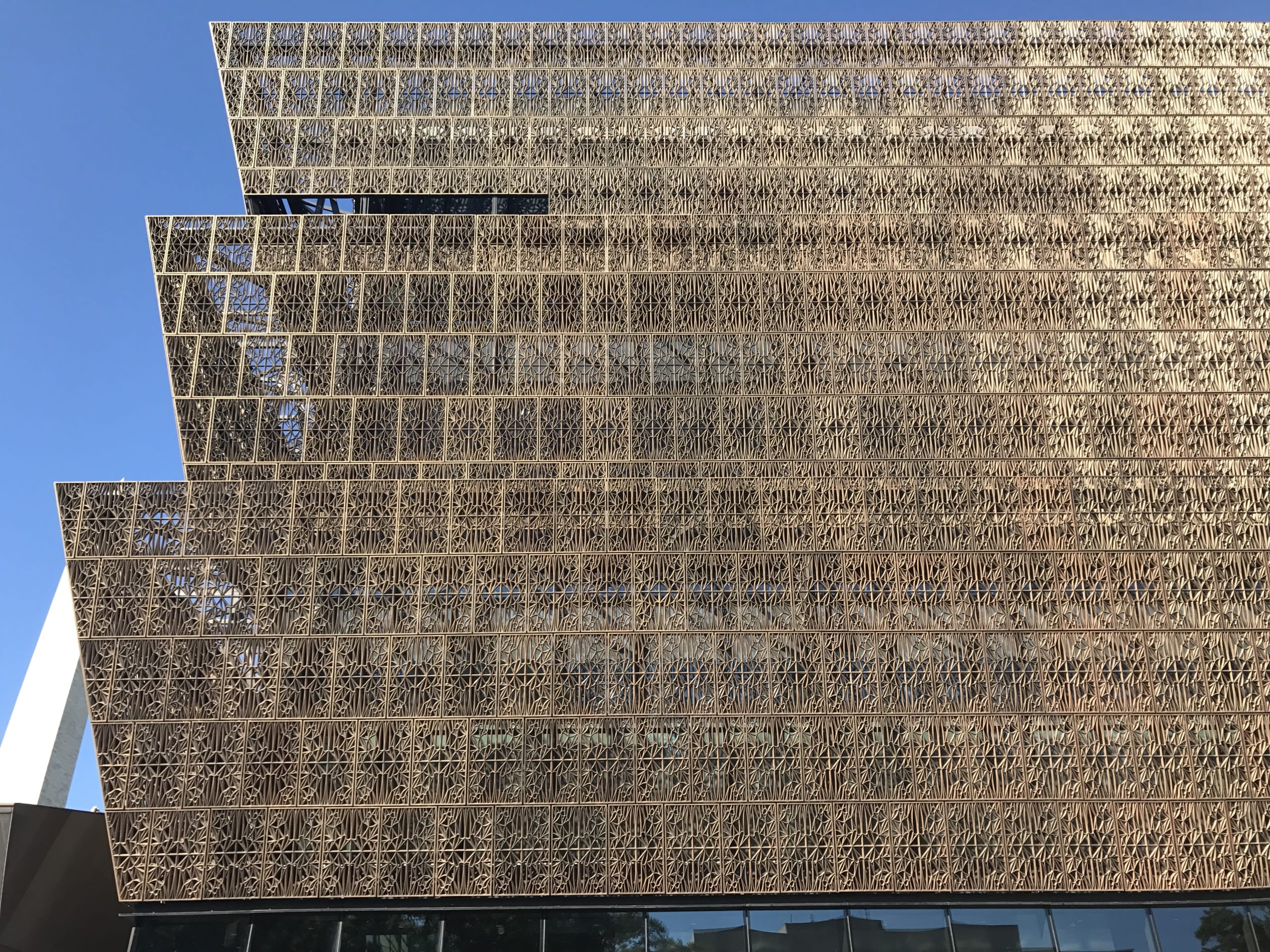

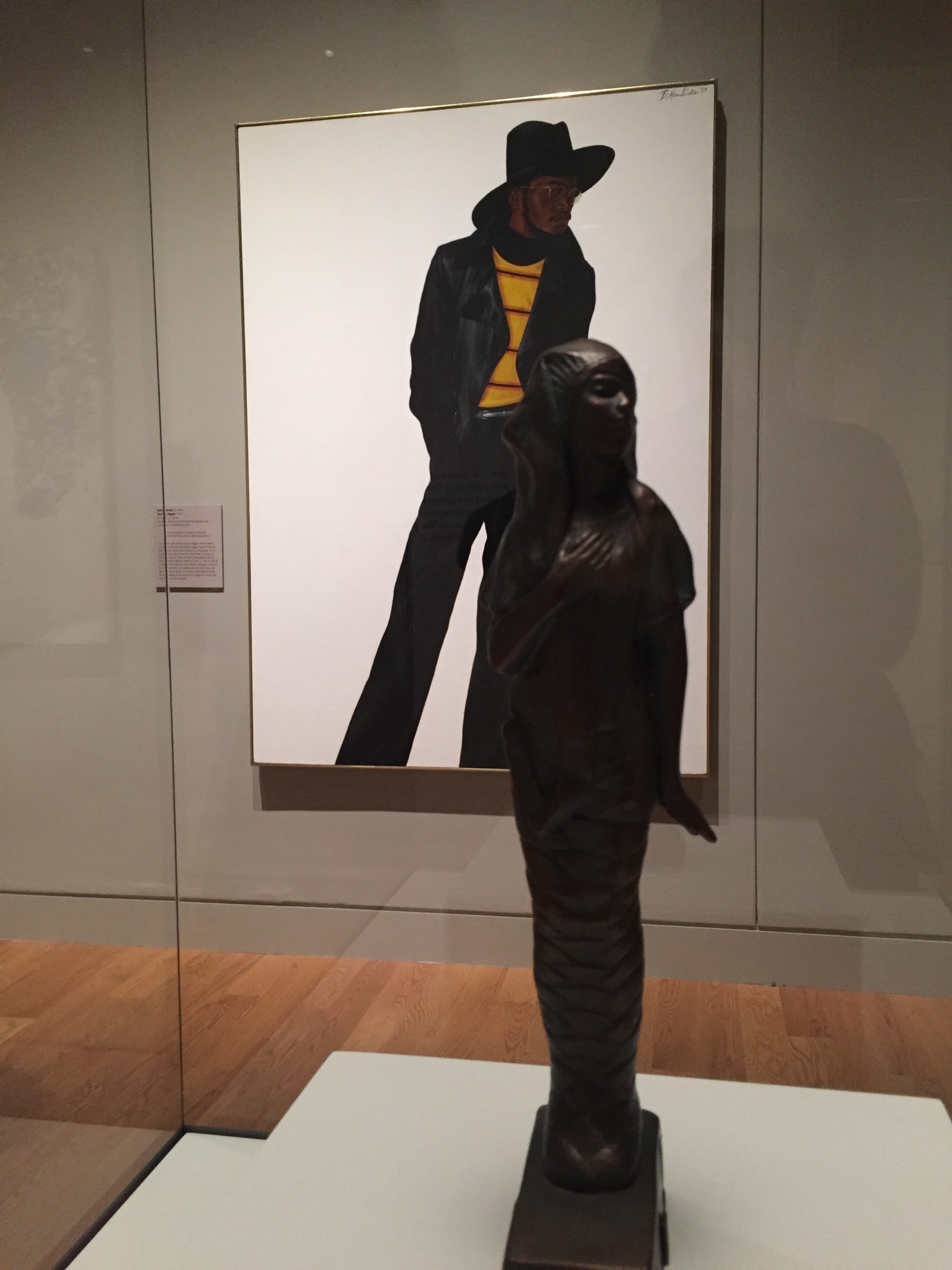

Majeed: Blake and I are here at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. We are discussing the architecture by David Adjaye, and how it has a kind of “manufactured authenticity,” in the sense that the building’s design is said to be derived from the shape of a Yoruba “crown,” which was never a crown at all—that association reflects a misinterpretation of an architectural element taken from a palace: a carved capital “crowning a caryatid” (pictured above in the image taken at the museum’s top floor).4 Regardless of the misinterpretation, the building’s insistent dark horizontality produces a satisfying difference on the National Mall because it is not a Neoclassical structure, for an effect similar to that of the EJI’s spaces in Montgomery.

Bradford: Just the idea of difference in the signification of the museum is important to acknowledge. One of the things I’m curious about is how this experience benefits from peak tourist season in DC. Considering the numbers getting up at 6:00 a.m. to get same-day tickets, it’s clear that there a lot of people who want to come here. I’m curious what their motivation is, and how they are engaging with this museum. To what extent do they want to engage with the content that’s specifically (and only) here?

Bradford [in the ante room before the elevator to the galleries]: I’m standing next to Bill Clinton. . . .That’s a museum piece right there!

Majeed: Arsenio [Hall] and Bill [both laughing]. This topic, which we will revisit as we’re walking around, is the role of photography and reproduction in this museum as it serves to fill in absences; there’s a lot of surrogacy and simulation in these spaces. Does it reinterpret some iconic imagery in doing so?

Bradford: The verisimilitude of photographs insists that these things actually happened, so that they can no longer “escape” from collective American memory. Because the narrative about the “black narrative” in America is that these things slipped out of history. The photographs, and there were other reproductions, provide a kind of evidence of everything from nineteenth-century slave auctions to black historical figures; reproductions show these figures were real and had dimension and presence. Bill Clinton playing saxophone on The Arsenio Hall Show is included here for Arsenio, not Bill!

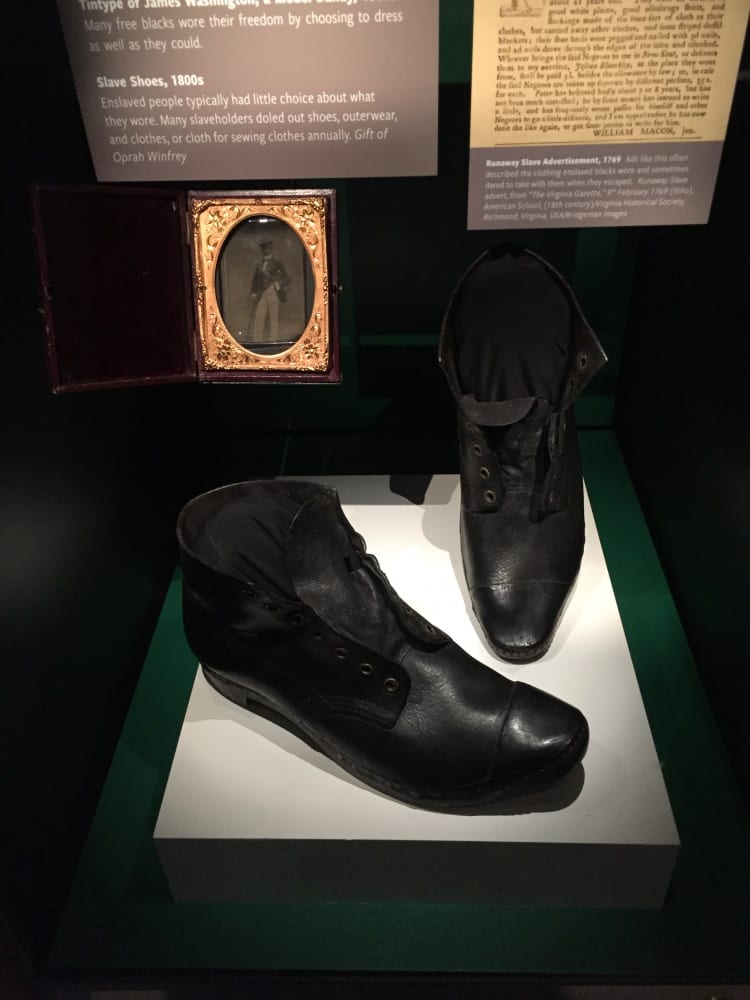

Majeed: Photography in its oldest rhetoric: evidence of omission, filling the active void. These are pivotal moments and they vary in their gravity: close by there is Emmett Till with his mother; a tintype from the Civil War; a portrait of James Baldwin. These photographs have various points of view and purposes as an indispensable device for the case the museum is building throughout the galleries: presence, dignity, valor, tragedy, entertainment. It’s a preparation for the history galleries, which will lead us through slavery, civil war, Reconstruction, civil rights, and into the present.

Bradford: The introductory montage hints at a more diverse set of narratives than “from slavery to freedom” that’s contrived into a lot of black museums. There’s much more scope, both to these exhibits and to the museum as a whole.

Majeed: That one being the triumphalist narrative that omits Reconstruction and ongoing forced labor, which is the primary trajectory outlined at EJI’s Legacy Museum in Montgomery: it’s much more interested in the ongoing repercussions of history directly in the present.

At the same time, in this museum, I like the way they’ve juxtaposed a kind of somber, formal portrait of a black family in the Civil War era with icons of the civil rights movement. Brings to mind Toni Morrison’s insistent dedication to “bear witness to the quality and variety of black life . . . [in a narrative that] would have to assume that we were still tough, and that our egos were not threads of jelly in constant need of glue.”5

You would think that kind of complexity would have logically led to future affirmation, as opposed to this police force in front of protestors a hundred years later.

Bradford: Something that I’ve found these museums speak to is just the normalcy of black life, on levels beyond just Martin and Malcolm and Harriet Tubman, these both tragic and heroic narratives—that this photo montage includes women’s social clubs and family portraits and people just being.

Majeed: Then you come to Spike Lee and Shirley Chisholm: it’s the popular, the historical, the political, the formal, all collapsed into one, as “just being” always is.

History: Where to Begin

Bradford: I am struck by the offering of complex narratives in this museum. So, instead of it becoming about Africa through the lens of the twenty-first century and what we want Africa to be, it seems more of a rigorous historical—you can speak to this—re-creation of Africa in the world of 1500.

Majeed: It’s imperative to dislodge ideas of Africa as “savage” and “primitive” in the beginning here because that’s exactly what furnishes the rationale for slavery. The museum must visualize the complexity of the cultures from which people were captured and enslaved in order to pack a punch here. This is to ensure that the viewer knows that we’re not talking about people who were coming from some sort of unmitigated backwards life, which is a total invention. Here the curators are doing this through western European representations of African cultures from the period, alongside the artifacts that are coming up on the screen right now: Benin bronzes, Afro-Portuguese ivories, Arabic calligraphy, the plurality of religions of centralized kingdoms that exist into the present. And I think they’ve done that through some loans from the National Museum of African Art and other collections of historical African art.

Bradford: The notion of Europe at the time was also very much fragmented, and we retroactively project unity from the idea of “white people” and “black people.” There are of course many different kingdoms and cultures represented that didn’t necessarily see themselves as unified; it was something that they became unified in their otherness, and I think it’s important to alert the audience to that fragmentary constellation.

Majeed: It’s equally important to remember that race did not exist in the same way we think of it today in this period; the binary you mentioned is in many ways a direct consequence of the slave trade coming into focus during the Enlightenment.6

The other thing that they’re doing here, which is interesting, is divorcing present-day, postcolonial Africa from historical Africa(s) to make the point that the continuity of certain cultures was attenuated by the colonial project.

Bradford: They also problematize the idea that Africa was something that had to be discovered by presenting it as a preexisting part of the Atlantic world, not something Columbus or whoever discovered. Africa was there, and it was commercially and culturally engaged at that point.

Majeed: We should think of Africa as a vital domain of the premodern world, which had many centers and many networks.7 Here we’ve got this notion of a global economy that is reflected in current discourses within our history of the world as being always interlocked and moving away from the idea of “discovering” culture, but also not immediately launching into the slave narrative. There was a period in west African history where there was a mutual dialogue between the Portuguese and the Kingdom of Kongo, which they show here in engravings of Capuchin missionaries in front of the Kongo ruler. The Kongo king, Mvemba A Nzinga (1509–42), converted to Christianity willingly, and took the name Afonso I. The kingdom had representation at the papal court with its own heraldry.8 So it’s critical that this museum doesn’t begin with slavery.

Bradford: It’s an important historical foundation that is generally omitted. It gives a sense of the volume of contact that shaped the then known world. They are also putting the emergence of modern Europe into context, foregrounding relationships between what became Africa in/for Europe, what became black and white. The museum is working really hard to tell a different story than “the slave ships came, took people away, and then in 1865,” and so forth.

I think one of the interesting things about this space is there’s a lot of people in it, but also, basically, you can’t see the space in full lighting. I don’t know whether that’s dictated by conservation concerns for the objects or just the reinforcement, or reenactment of an experience.

Majeed: It seems to me, that this has little to do with the objects, since we are looking primarily at reproductions and metalwork in here. Rather, I agree that they are trying to give you a haptic experience moving from darkness into light. Much of this visit is linear don’t you think? How much do they want to absolutely be sure you see, and before you are allowed to make choices?

Bradford: Right, and in this space it feels like you prime the audience, but there’s not a central unifying object or destination. And like you said, it’s a haptic and cumulative experience that does not center on a single object or story.

Majeed: Certainly in the first space you were confronted with the history, but here, once you emerge from the Middle Passage, into the role of various countries, you can become much more autonomous in the way you experience the rest of this reconstructed history.9

Bradford: Yet, there is a degree of hierarchy with certain objects versus the cases/displays. The Albrecht Dürer depiction of an African man is singled out, for example.

Majeed: It’s a really sympathetic portrait, it seems, of an African in the sixteenth century (even if it is a reproduction). The other thing that the curators make sure to do, alongside the total dehumanization of people, is to show that their humanity wasn’t so far from reach.

Dialectical Space: Curating Contradictions

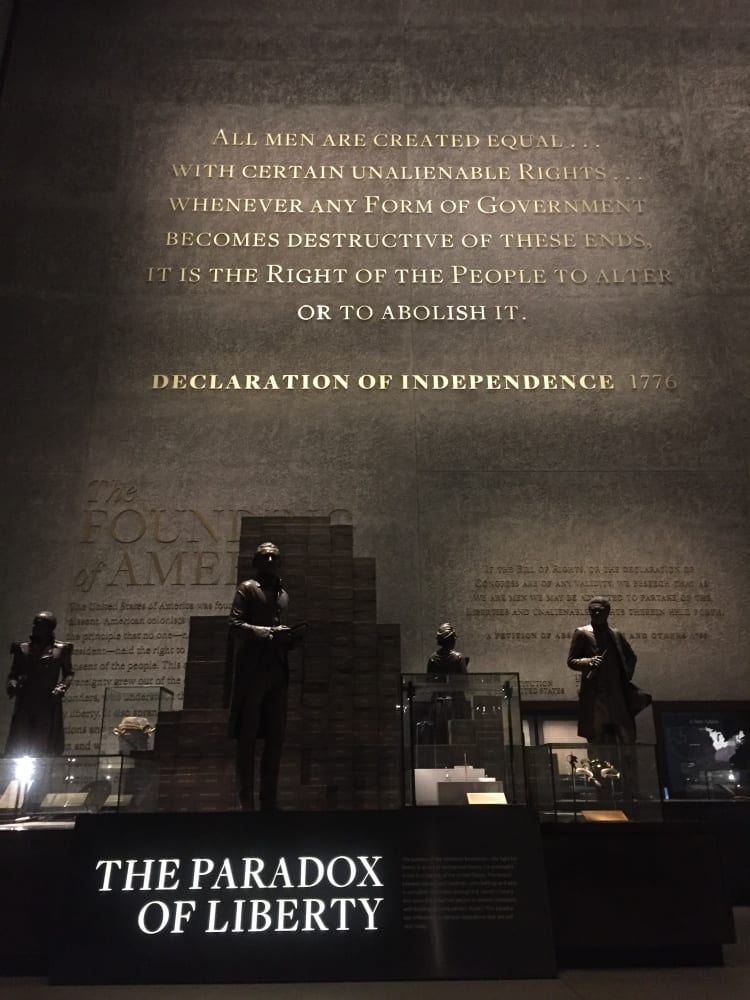

Majeed: We are at the Jefferson portion of the historical galleries and I think a lot of people have found this to be very successful as a revision of Jefferson as a person without discounting his importance; it’s a more complete account of everything he was.

Bradford: It introduces and reinforces the paradox—not only the paradox through contemporary eyes but also the paradox that was there all along and acknowledged by Absalom Jones and others in the 1700s, contemporary with the Declaration of Independence and so on.

Majeed: We emerge from those very narrow low-ceilinged historical galleries into this big, multistory room with Jefferson at the center. Do you think they got this part right?

Bradford: They’re tapping into conventions of how we display the founding fathers and the foundation of America, but they very explicitly introduce slavery—this section is called “Paradox of Liberty.” I feel like they got it right. There are definitely some props used to create a mise-en-scène—the bales of cotton, for example. That level of entertainment, we’ll say, isn’t mutually exclusive from delivering some of the powerful messages and introducing some of those challenging questions.

Majeed: They do so without taking away Jefferson’s dignity. He still has the stature of somebody memorialized in bronze, but the backdrop dwarfs him in scale with the names of his slaves. Of course, here he has turned his back to that reality.

Bradford: It gives Jefferson and Jeffersonian ideals a fuller context that way, and a fuller representation; it conveys a sense of intellect and hits all of those buttons while at the same time giving those hidden figures a presence.

Majeed: Even though their presence is through objects, not as people.

Bradford: That’s true. They might not have had another way to represent them. These individuals in the 1700s might have just been lines on a ledger.

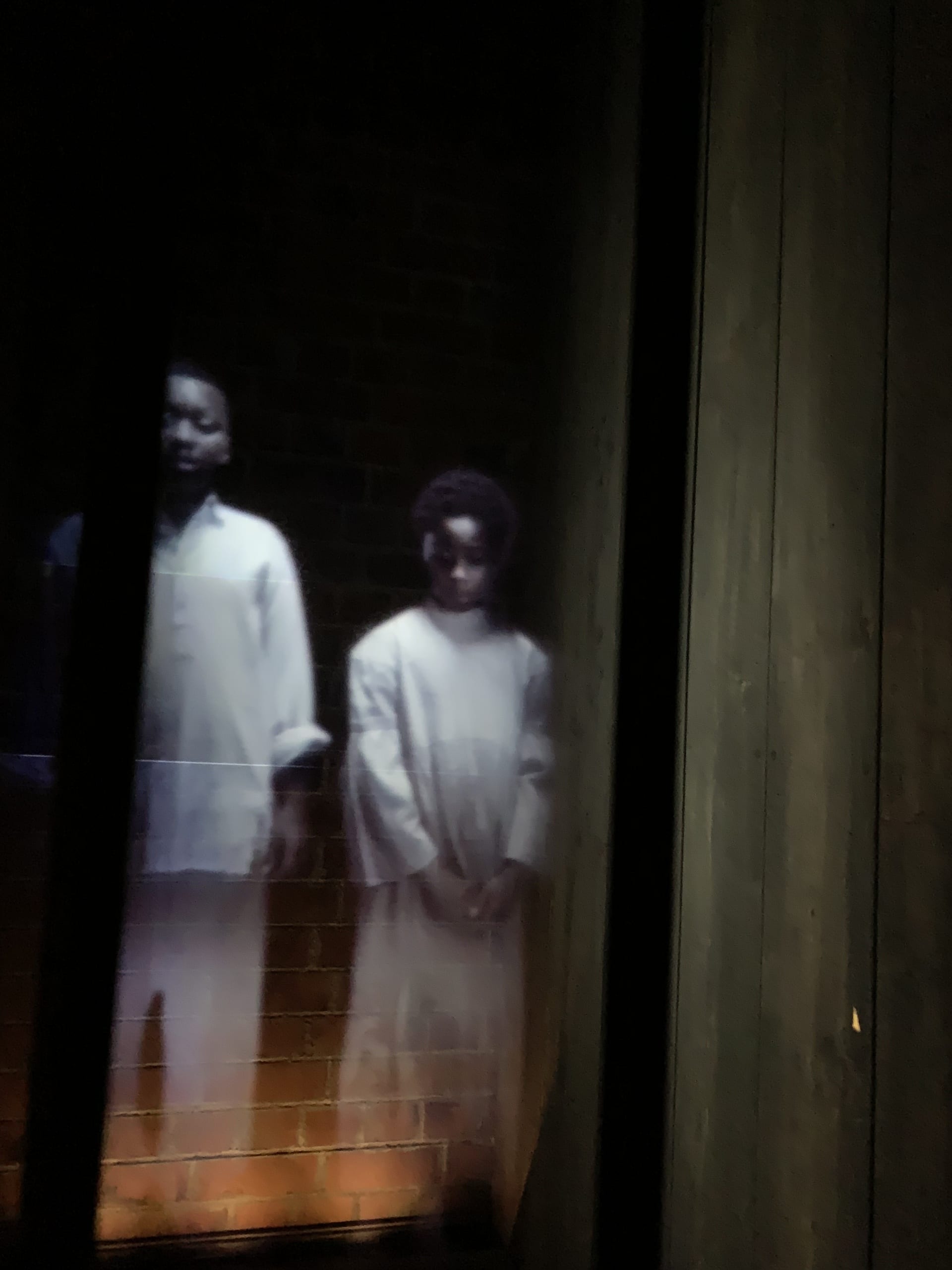

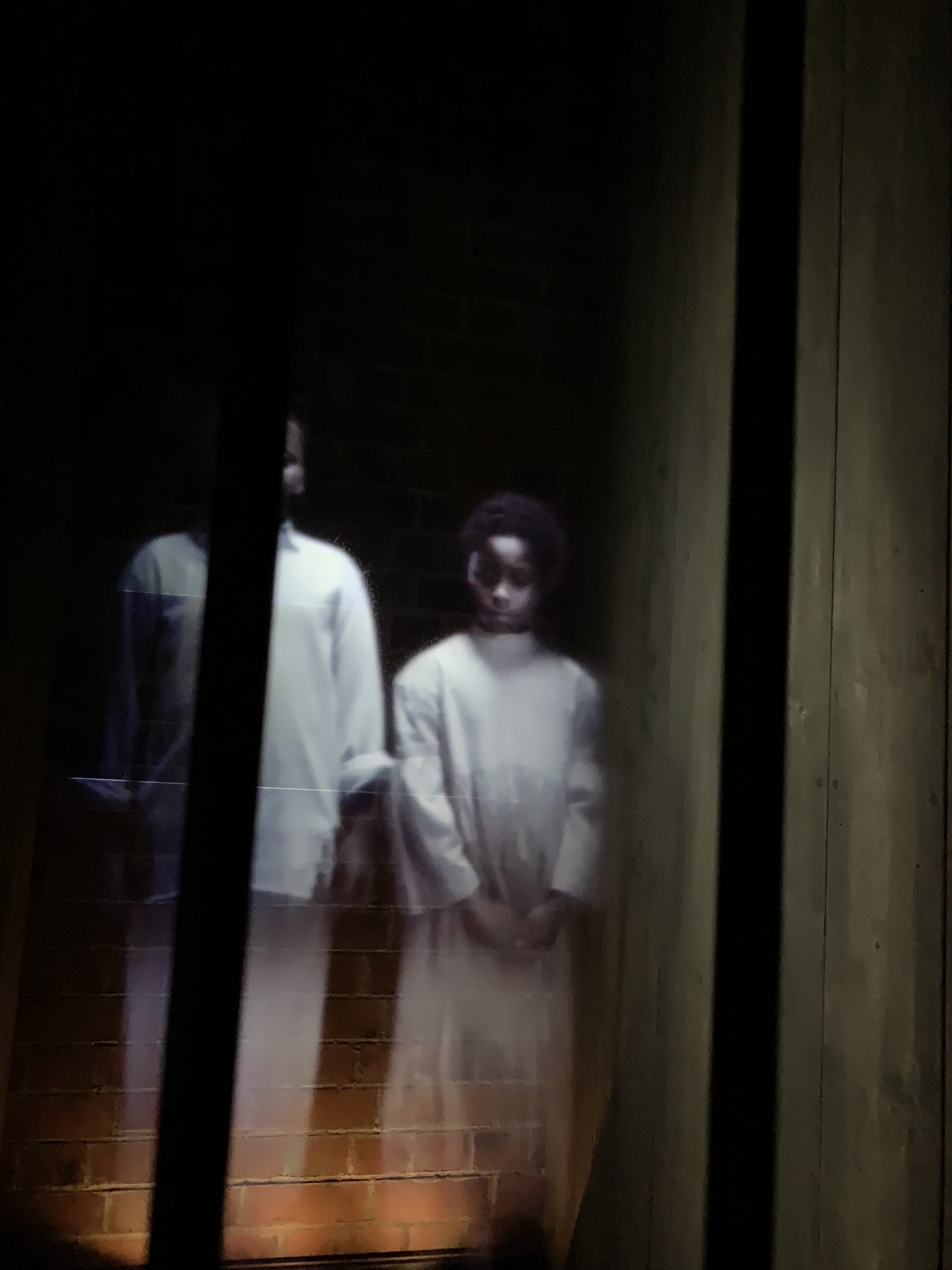

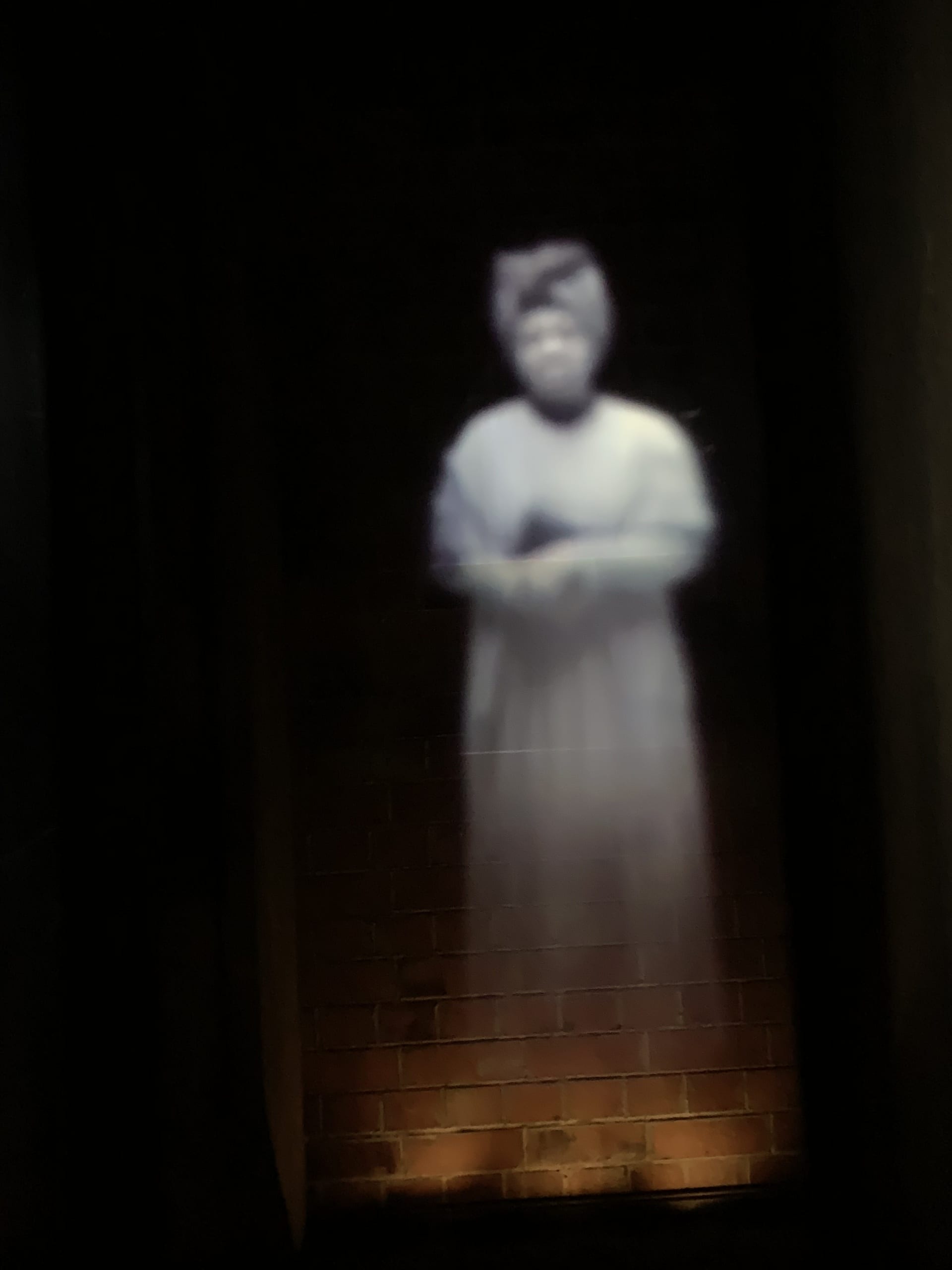

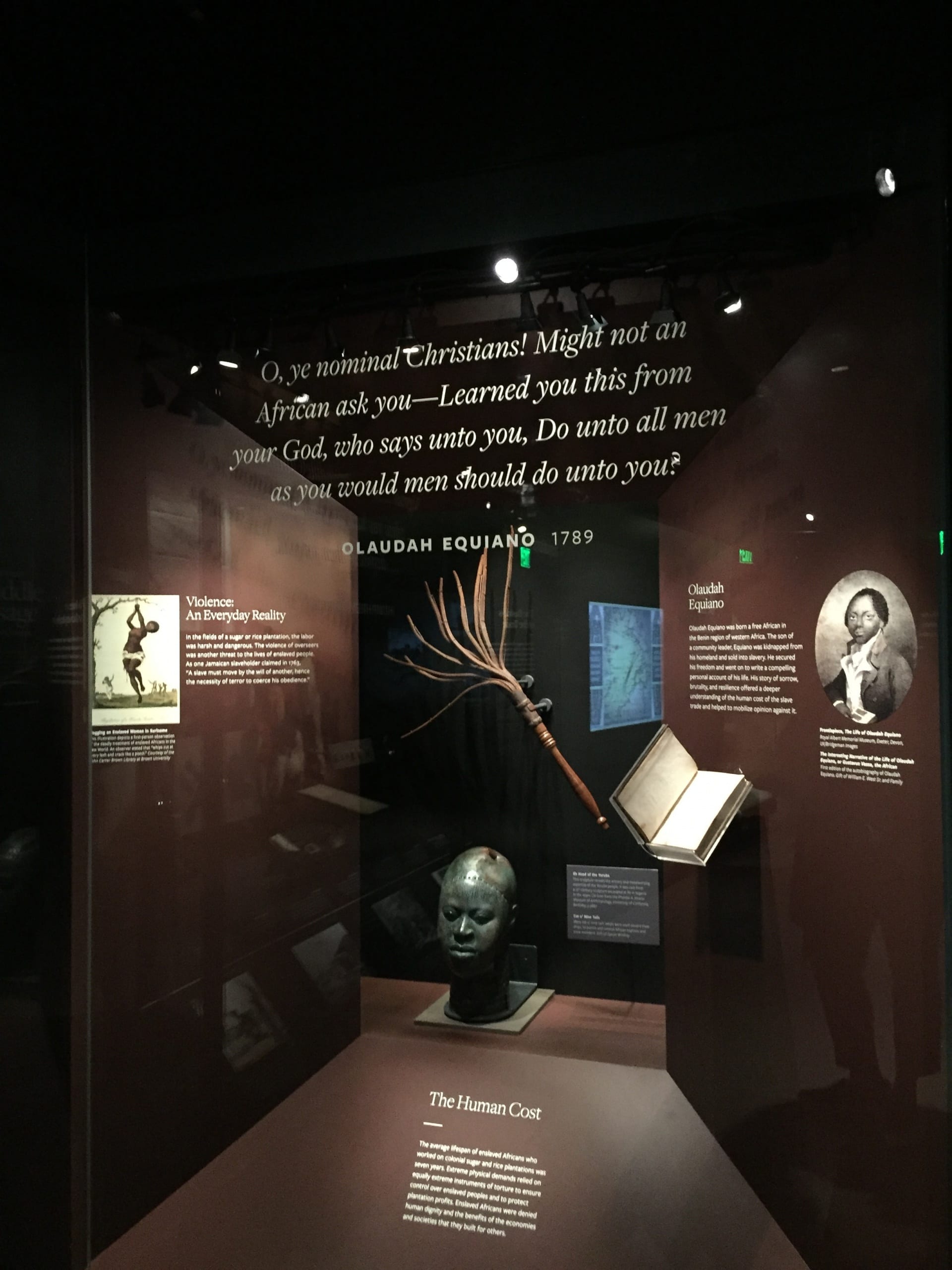

Majeed: It’s the inescapable anonymity that Montgomery tries to fill in through different museological devices. The holograms, for example, from the same time period, accompanied by contemporary voices reading historical accounts, were haunting and quite moving. Again, it’s interesting—the panel that you and I were on at the Frick a couple months ago of “not being in the picture.”10 We were sidestepping this point. I was of the mind that the reason why people aren’t in the picture is because they literally were not in the picture, and these absences evince the differing priorities of history. They were not pictured for a reason that transmits their position in history vis-à-vis the producers and consumers of these images.

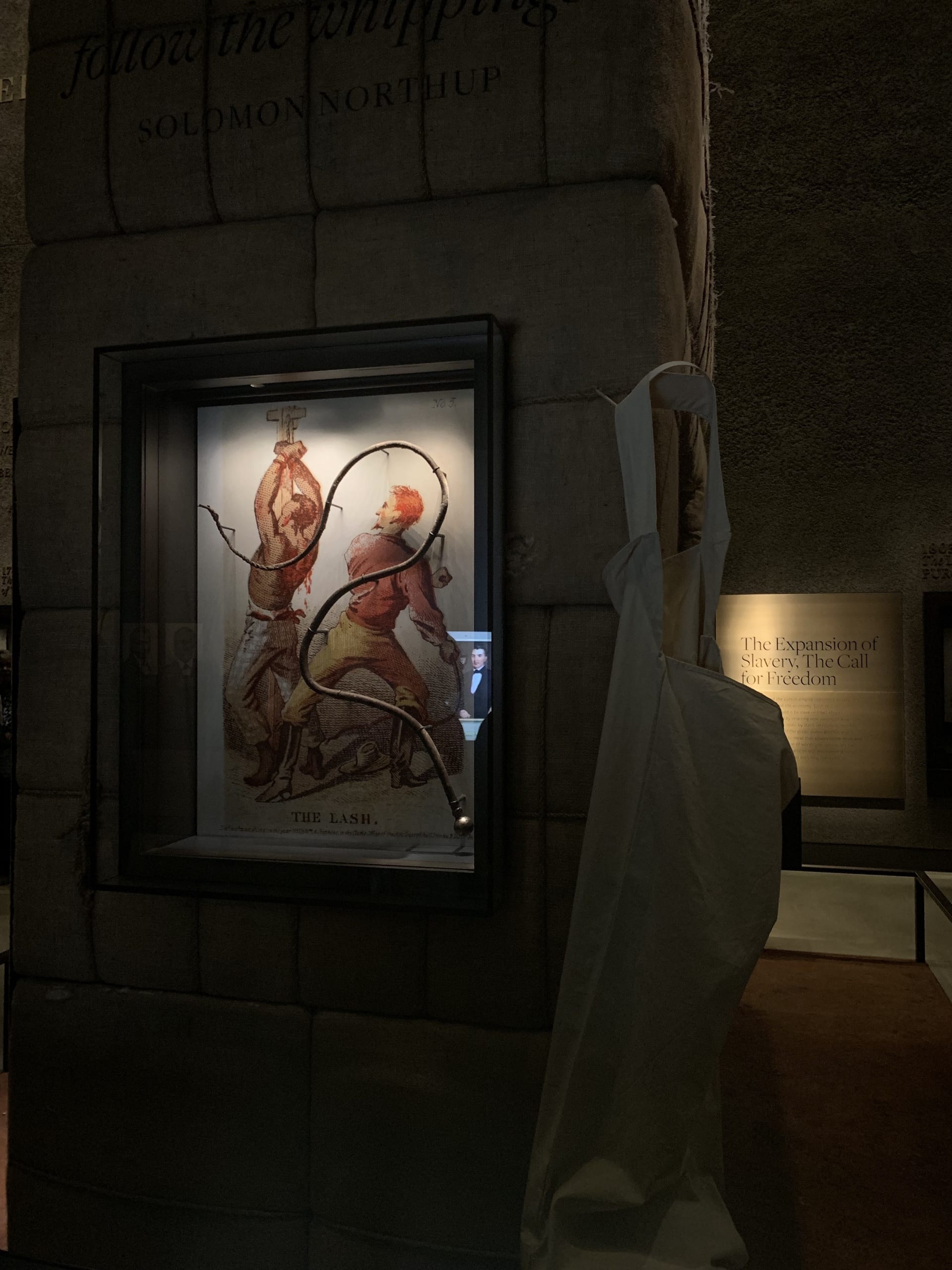

Next to the King Cotton display there’s a representation of whipping. The way they’ve done this here is to resuscitate an object so it can participate in the narrative of the reproduction. An actual lash silhouetted against the representation of a beating. We’ve seen this before: they had the cattail whip earlier, but it was fanned out in a way that nearly made it an aesthetic object. I wonder about that and the inescapability of aestheticizing objects in a museum context.

Bradford: The museum is, in and of itself, a contrivance to maximize the impact of these objects or to tell those stories, and sometimes you have to play these tricks. That’s part of the game. Taking the whip and superimposing it on this picture, I don’t want to call it the best and highest use of the object, but it is a way to make sure that you understand these things in context.

Majeed: There’s a certain amount of restraint here: there’s a surplus of images elsewhere that are more graphic than the worst things on display in this museum. I wonder about the kinds of decisions that go into accumulating artifacts to make this particular point here, which is cotton, commodity, people and then the necessity of expending people to make it. The tactic of paradoxes, putting two contradictions together you have to reconcile, is effective in this environment. It’s a dialectical space. For this reason, it’s important not to have any originals in here, because then you’re not venerating the singular object. The museum is treating it as an illustration of the past, not as an object of art, which a lot of these paintings are in other museums.

Let’s turn to the other didactic supplements here; I notice that the domestic slave-trade map occupies a smaller area here than it does in Montgomery, likely because Montgomery had one of the largest slave markets.

Bradford: The story in Montgomery begins with the slave trade, and they don’t have an ambition to trace a more fully expansive arc; their story is about a kind of persistence of white supremacy that starts in 1619 and continues to the present. Whereas this museum tells the story of that larger context, more globally.

Majeed: Although the surfeit of stimulation in both museums is similar, among the experience of words, images, objects, oral component, haptic component. The EJI memorial, on the other hand, takes its cue from the model of Holocaust memorials, which frequently insist on contemplation activated by absence. In that space, we have a path which forces us to circumambulate in a ritualized manner before we reach the covered commemorative spaces. It begins through confrontation: the names on those slabs are at eye level, and as we descend, they ascend, in a powerful reminder of the act that is to be remembered. Absence in that memorial is all the more effective because it sits in view of the monolithic, bombastic sculptures of people like Jefferson Davis, so prominently commemorated on the Alabama State Capitol. That is the context that EJI is responding to with restraint and even reconciliation.

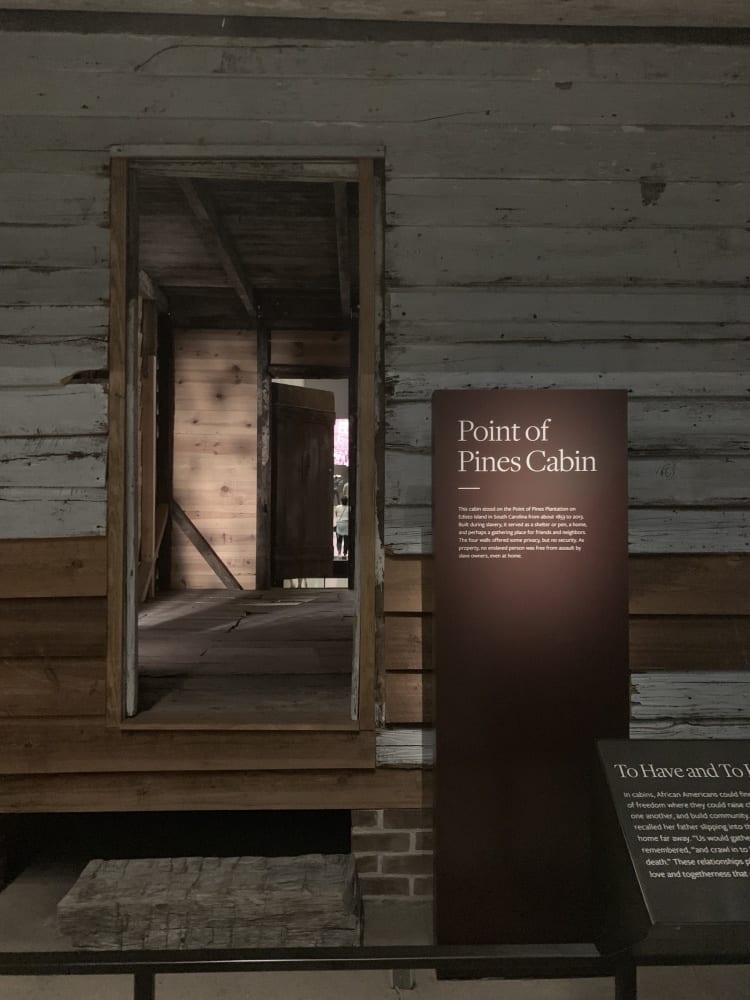

Versus this museum, which does not have the same urgency in some ways, even though it is a place of veneration, a place of pilgrimage. Here we have a kind of ruin inside the museum: an entire slave cabin (the Point of Pines Cabin at the NMAAHC).

Bradford: We are accustomed to appreciating so many different types of aesthetics in 2019 that you end up looking at this and thinking, you know, there’s a certain kind of simple beauty to it. Whereas the label is pointing out how completely available it is for anybody to come in: it’s not private and it’s not a protected space.

Majeed: Which is how it was when it was inhabited: there was no expectation of privacy. Although here there is a kind of voyeurism too, since this was not made to be looked at but was designed for a minimalist functionality. It strikes me as strange the way in which it sits here as an object to be scrutinized.

Bradford: We look for things that might have never been there, seeing it in this space.

Majeed: I think back to the distinctions that Aloïs Riegl made at the turn of the twentieth century, about historical value, age value, and artistic value, that outlined how we memorialize or monumentalize certain things from the perspective of the present, which together represent a system of signification.11 What does it say that this was on its original property until 2013? Those plantations have been turned into tourist attractions: have you been to any of them? I’m thinking for example of Boone Hall just outside Charleston, with its “Slave Street.”

Bradford: I’ve seen and have my own issues with how those narratives are manufactured, but putting that aside, it’s important that we’ve arrived at a point where these things are seen as valuable and historic. It’s not always the heroic things that are historic.

Majeed: Certainly, and that will be the case throughout this museum, I think. It’s using objects to elicit emotions and conjure empathy, among other things. That is not the case on site, at a plantation where I’ve seen people reenacting bucolic scenes from the time period. So someone will be in such a cabin sewing, for example, which is total pretend and a different kind of voyeurism, which I have recoiled from.

Bradford: You know, it’s almost a reflection on us, in terms of what we need, to understand or to feel history.

Majeed: Absolutely, and to that point: there are no white people in this narrative; they are not the protagonists. At the same time the immersion in the slave narrative is relentless, to the point where we just observed a grandmother with her grandson wish aloud that they had an alternate . . .

Bradford: . . . could move on to the lighter, more positive and celebratory portions of this history.

Triumph and Ambiguity

Majeed: Once we get into the civil rights era, I wonder how much of the responsibility of these sections is to confirm what the audience already knows and to valorize that, versus introducing lesser known narratives. Is there anything here that they’ve resurrected, that maybe the general public wouldn’t be really aware of?

Bradford: I would argue no, in a way, because this is iconic black history. There’s Angela Davis and Muhammad Ali and Soul Train, and you’ve got Fannie Lou Hamer and Jesse Jackson and the death of Martin Luther King Jr. and the riots. It’s all, in its way, a history that I feel like I was immersed in, but it’s also like watching a movie of that history again.

Majeed: Where these narratives have already been visualized, whether that’s through documentary or photography or textbooks or teaching, even museums are limited in their creativity of representation, and so they can end up mirroring previous interpretations or re-presentations of the past.

Bradford: This is also an era with a very explicit narrative intention; it’s the time when Ebony was self-consciously the Life magazine for the black community. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, and it’s almost too close in time to start to pull at the threads and look at the complexity of these moments. In my own historical examinations, the people who lived/made this history are still around to valorize their roles in it. So it’s hard to really pull back when those people are still telling the same stories.

Majeed: Is this what happens when one remains so close to the past that one is now representing from the point of view of the present? What I keep feeling is the artificiality of this museum’s vision, which creates distance from the very recent past that today’s viewers have directly experienced. I wonder, is it possible to have something more than these kiosks of icons and relics (they are like little altars)?

Bradford: There’s also something about these narratives that we’re trying to protect, because they’re so close. We have to believe certain things about Martin Luther King and Muhammad Ali. And as we were discussing before about problematic figures, part of the challenge of being black is you only have so many heroes. Be careful with them, historians.

Majeed: That’s really, really slippery, because the one thing that I wouldn’t want to do is devise a new set of standards for histories that have been marginalized. I want the same rigor, otherwise with such exceptionalism there is a risk of it remaining marginal and becoming trite. That’s not to say that there shouldn’t be alternative sets of questions.

Bradford: Right, right. The Afrocentric version of black history thirty years ago was trying to elevate it to this level and might not have been very careful making the points we are discussing. It was a zero-sum history that didn’t lend black history the same amount of complexity that accommodated problematic issues alongside heroic outcomes.

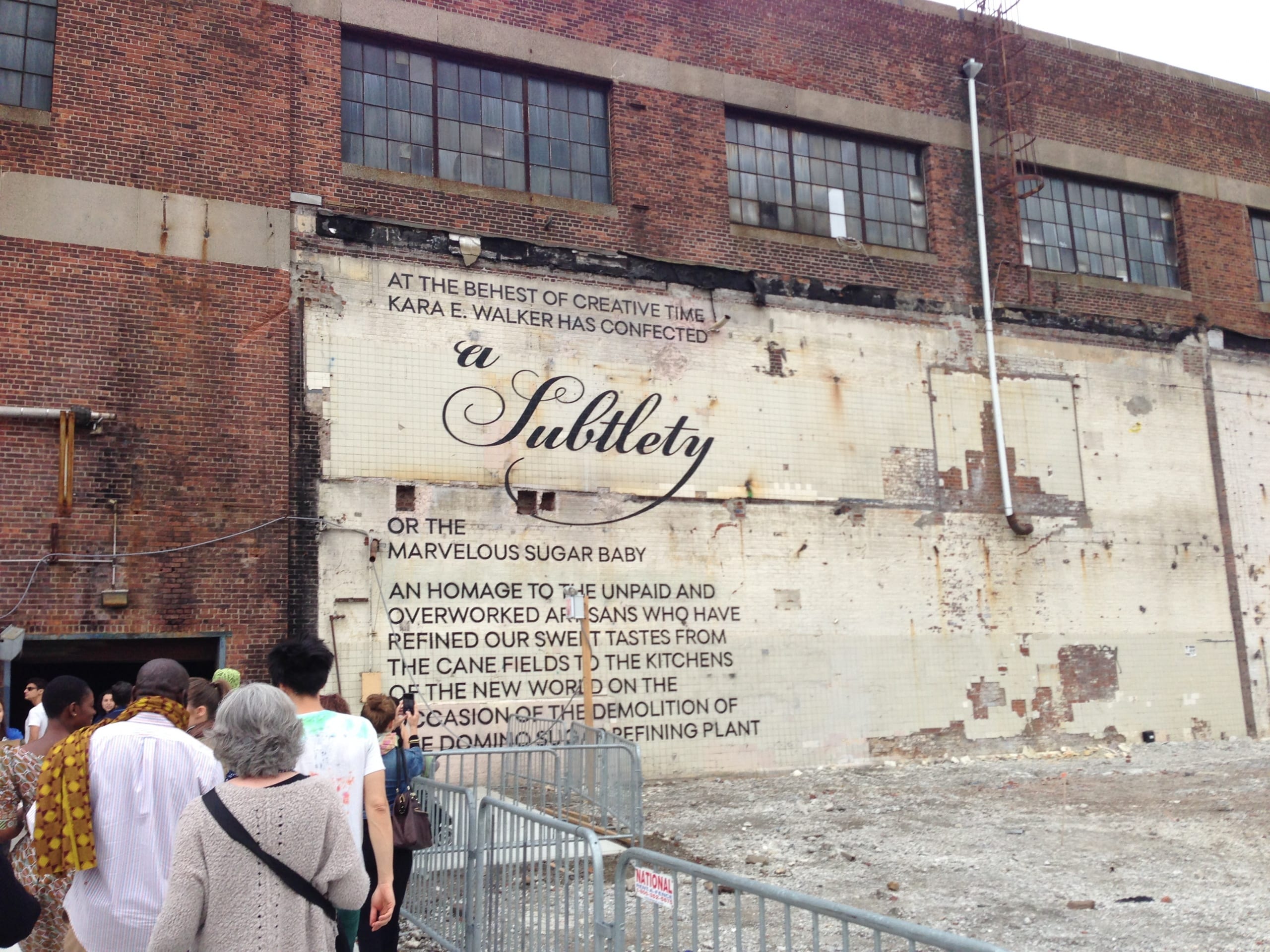

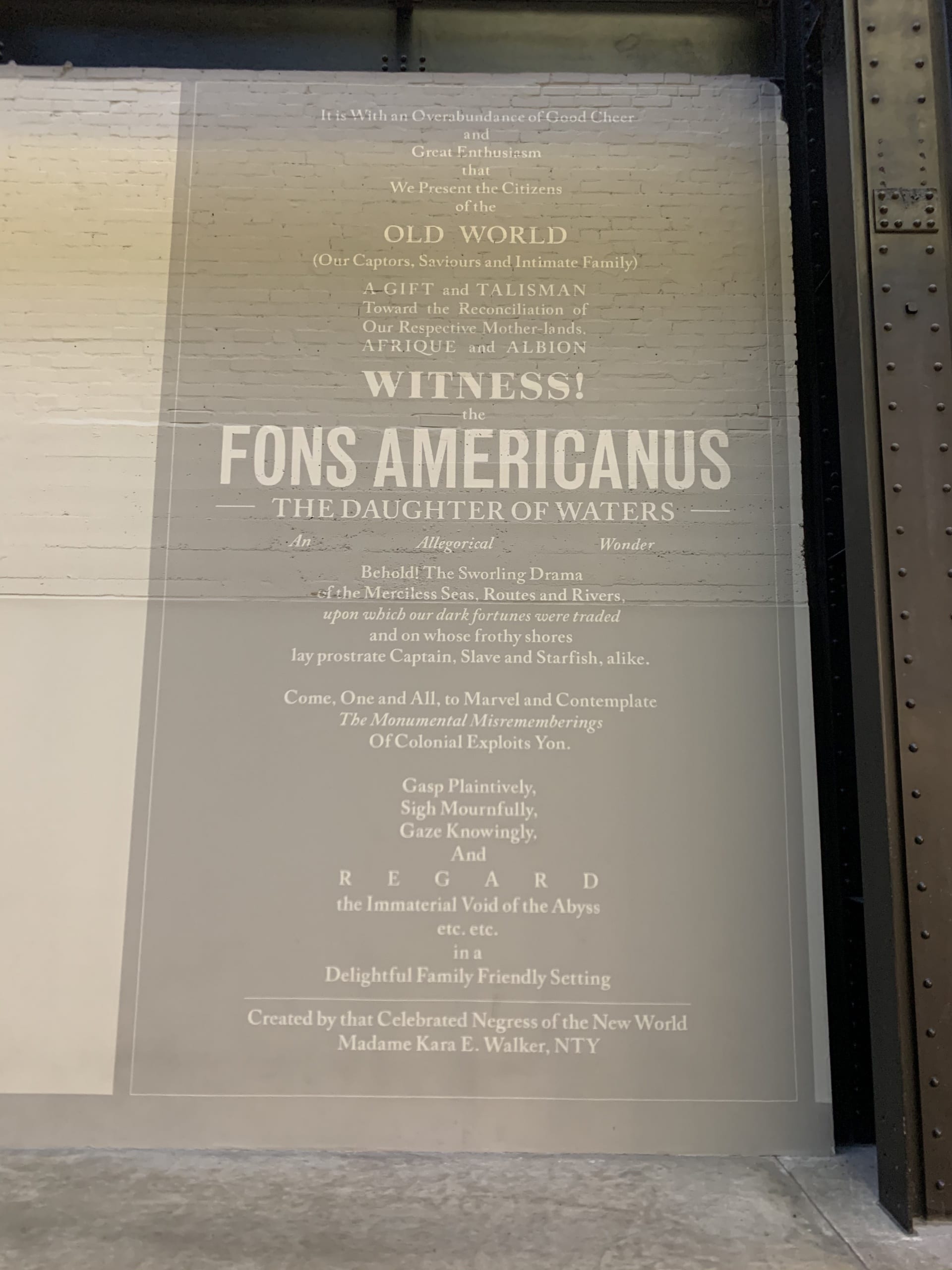

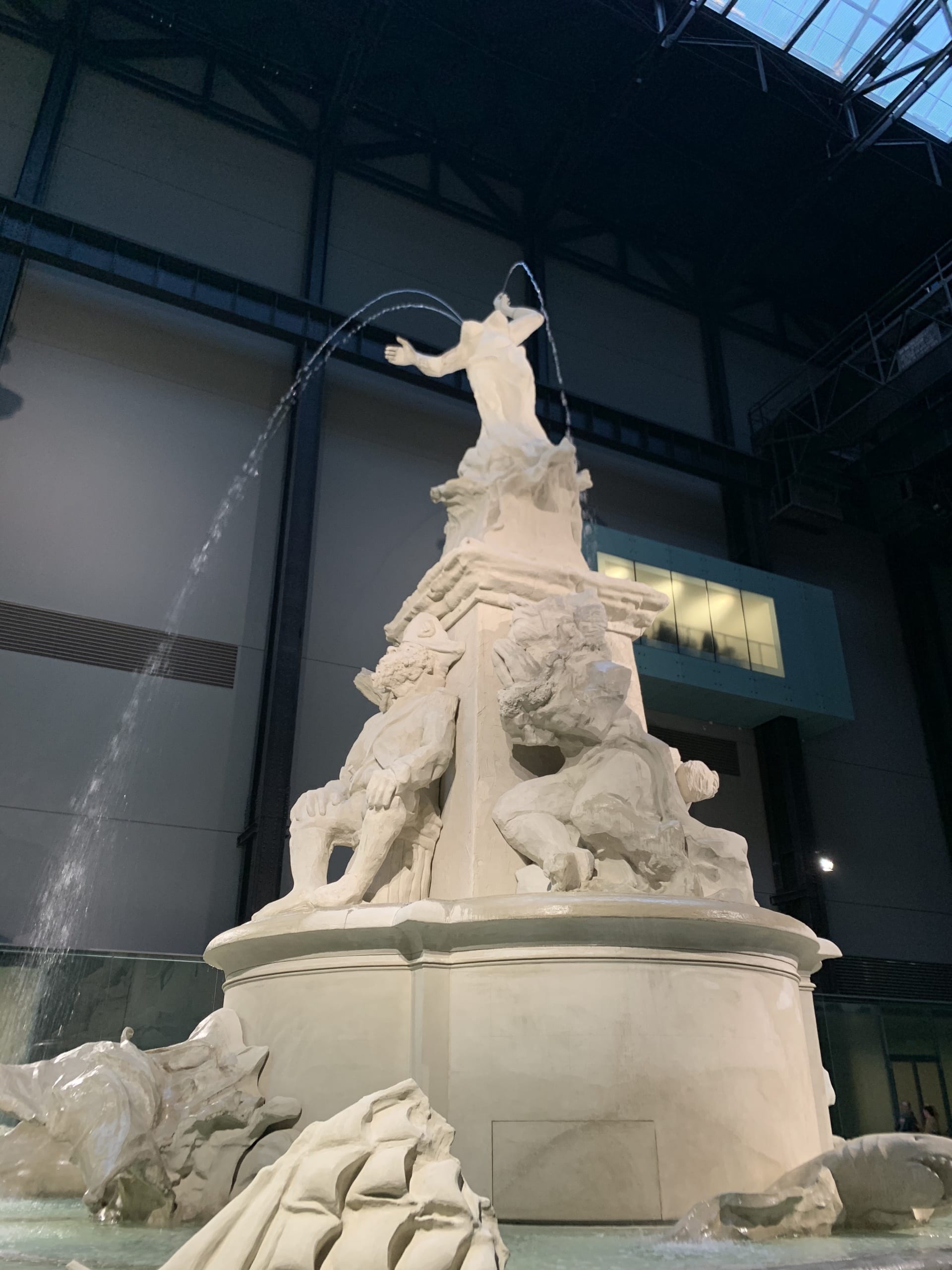

Majeed: How much can one problematize the accepted narrative at the museum of record? We have to rely on other forums, like the memorial and museum in Montgomery, for that complication to enrich what we know and how we think about it now. Take Ava DuVernay’s film Selma (2014), which gives a more complete picture of Martin Luther King, for example, or Kara Walker’s public installations at the Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn, A Subtlety (2014), and more recently Fons Americanus (2019), at the Tate Modern in London. DuVernay and Walker are making us think about women, without whom this male-centric history is uncomfortably close to hagiography. Nevertheless, this museum furnishes a solid point of departure for others to deepen and question black history. People come to see themselves here.

Bradford: That’s a really important notion, that people come to see themselves and people want to be, in this case, literally uplifted that way. They only want to have so much truth, only want to have so much ambiguity.

Majeed: And shouldn’t women have a more prominent role in that sense of “uplift”? Considering the crucial role of certain women, from Harriet Tubman to Rosa Parks, what is the role of black women in this museum?

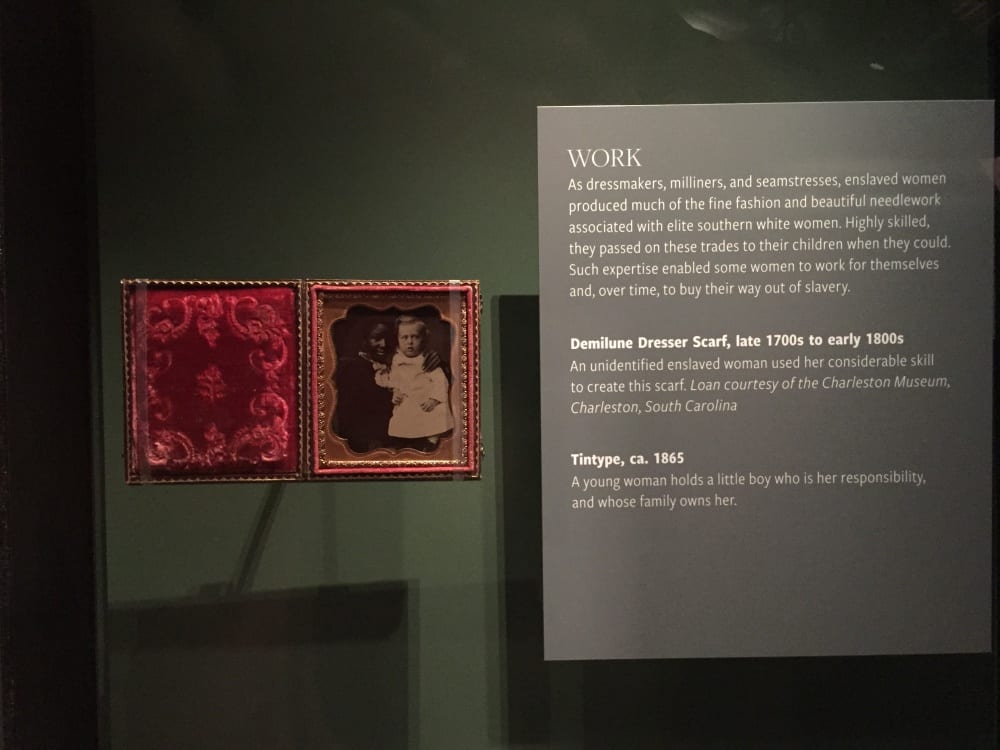

Bradford: I don’t know how the role of women in early discussions of slavery is addressed or referenced in this museum: perhaps by proxy when domesticity is discussed.

But then as you move more into discussions of civil rights, certainly I think women have a strong presence in that.

Majeed: Inevitably, but I did notice the one thing now that I hadn’t before: that in the history section, they emphasize African queens, like Njinga of Angola.12 And, of course, Sally Hemings behind Jefferson, notably an incorporation of absence. It brought to mind Martin Puryear’s A Column for Sally Hemings, which he made specifically for the Neoclassical rotunda of the American pavilion at the Venice Biennale (2019). That tapered fluted column-pedestal from which a bronze post rises, the shackle giving it an anthropomorphic presence as a surrogate for that which was always in plain sight.13 Walker’s Fons Americanus more explicitly monumentalizes the role of black women in American history; heroizing black women could be a bigger part of the narrative in this museum. The sexual violence directed at women is not represented but implied; that’s what Baldwin was talking about.

Bradford: As you were discussing it, I was thinking about the Emmett Till Memorial. Men in most cases were the victims of these things, which Montgomery is all about, and women were there to mourn. At least that is the narrative we are presented with in this museum, even though we know that women were also subjected to racial violence.

Majeed: Perhaps most well known is the horrific lynching of Mary Turner, who was eight months pregnant, in 1918 for protesting her husband’s murder by a white mob.14

However, in this museum, women are presented as mourners, or the bearers and transmitters of memory; which also means that they can control the story. It was Emmett Till’s mother, Mamie Elizabeth, who insisted on the open casket. You look around, and there are a lot of older black women here with their grandchildren. So much a part of this history is the idea of not forgetting, which is in visible tension with, “Okay, I need to get out of here.”

Bradford: The tension between “This is important” and “I can only take so much of this.” This is important, but for many people it’s a “memory” lived every day.

Think about intersectionalities; think about other ethnicities that make up the American demographic. That is something that is fairly new. In this space, race is specifically black and white. Yet, across the African diaspora, across other nonwhite ethnicities, again, the connection with Jews and the world, some of those things were contentious in some part, because the idea of solidarity against oppression was not encouraged (to say the least).

Majeed: Here the model is segregation of black and white. But if you look to South Africa during apartheid, there was an in-between category of not black. Such hybridity is implied here; for example, there are sections on anti-Semitism and anti-immigration as anxieties of American history. Is this museum the place to have this conversation?

Bradford: That’s a really challenging question, and it’s important in terms of what constitutes the struggle against oppression, against exploitation. How do we start to see their other manifestations, where there’s the track record of homophobia and, in terms of the civil rights movement, of misogyny. How do you represent a movement for social justice that is thinking about social justice in more than one dimension?

Majeed: Without getting into the ambiguity and disingenuous nature of this “all lives matter” rhetoric. Not to create equivalence, but to add a moral dimension that can hold contradiction and progress parallel to each other.

Bradford: It also starts to transform the connectiveness of these social-justice movements. They’re not just atomized and single-issue focused; these systems of oppression function on many levels and impact people who could be our allies. The EJI museum addressed this more comprehensively; white supremacy didn’t always have the same target, and those groups that were excluded sometimes realized that other demographics could be allies.

Majeed: This history hasn’t been only black and white; it has been white and everything else. And that’s more damning, actually, than I think this space allows.

Editing and Animating History

Majeed: [In that massive elevator that was packed, which leads unto the historical galleries, Blake and I were talking about whether or not Bill Cosby is still included in the museum. Along with other people who have been dethroned in some way—what do you do with them?]

Bradford: These are people who are irreplaceable and very much part of black history; their contributions can’t be just written out in this comfortable way. We can’t pretend they didn’t exist. We can’t pretend it didn’t happen, in terms of the positive impacts. Bill Cosby’s crimes went back fifty years, but the process of making him accountable for those crimes was only the result of Hannibal Buress’s comedy routine going viral. I don’t know that institutions have really figured out how to handle this complexity.

Majeed: There’s even more at stake with somebody like Bill Cosby, not only for the black experience but also because there are so many fewer people who made that kind of an impact across race, ethnicity, and class. Certainly, taking that out, there’s not a lot left. With the white experience, there’s a plurality of people to choose from (and omit).

The role of music becomes so much more prevalent than television, because it is more portable and exportable. This music of the 1960s and 1970s was hugely instrumental in crafting modernity for newly decolonized regions. For example, in Pakistan, my father turned to black music, maybe as a way of marking modernity over the colonial past (but also because it was cooler than anything else).

Bradford: The inclusion of signature artifacts, as a shorthand for black people’s popularity and success in entertainment, feels like a “mission accomplished” banner sometimes.

For example, in the music galleries the biggest problem for 2019 is Michael Jackson. There’s a large projection that showed the “moonwalk” from the Motown 25 anniversary television special of 1983. This is the question I have, the conundrum I have of, you can’t tell black history without Michael Jackson, without Bill Cosby, certainly. There’s triumph—the Jacksons dubbed their 1984 concerts the Victory Tour—but that hasn’t mitigated the ongoing struggle and trauma. Our acknowledgment of those kinds of issues is new enough that museums haven’t really effectively strategized or been transparent about what they are going to do in the wake of these uncomfortable truths. What are you going to do with the museum display when you find out about these things?

Majeed: I agree with you in the sense that if you start editorializing history according to today’s standards, we would really not have much left. These realities challenge conventions of museum representation. There’s not just one way of commemorating or memorializing, and one doesn’t necessarily have to celebrate to include.

Bradford: That’s the crux: history doesn’t “end,” and there is no resolve. I would be more satiated with these spaces if they allowed for these competing complexities to coexist without ending with “Obama out,” you know?

One of the things I was struck by the first time I came here was that the museum was pretty thorough in terms of constructing a contemporary history that was inclusive. They’ve chosen to go deeper and hit some of these, say, lesser figures, but figures that indelibly existed. We return to that question of authenticity around blackness that has been in contention since Alain Locke. What does it mean for black people who are not included in these narratives? We have Anita Hill highlighted but not Clarence Thomas, for example.

Because of the conversations we’ve had about history and museums and omission, one of the things that has been central to black history has been depiction, has been photography. Vernacular photographers that provide evidence of black existence and black humanity are so important to a place like this.

Majeed: That’s also self-possession, through self-representation, for posterity, through studios and later through more casual snapshots. Photography has played such a big role in representing the ordinary humanity of recent history for those who are not represented in the metanarratives; it allows for an autonomous fashioning of identity that rejects the identity that is grafted onto you by society at large.

Bradford: The National Museum for African American History and Culture in that way is a catalyst for performing black history—that the existence of this place, the opening of this place, part of its significance, wasn’t just what it held in the experience here, but the idea of capturing black history in an archival manner.

Majeed: Evident in the way they’ve created moving images from still images so as to animate the past, because looking at a static image doesn’t drive the narrative as effectively.

Bradford: The Ken Burns effect: where history becomes storytelling.

Majeed: When you animate these images, you give veracity to the story that you’re telling because it seems like you’re recording it, but you’re not recording it. It’s already recorded and it already has a point of view, but you’re giving it another point of view but erasing your editorial component, which is kind of mesmerizing.

Bradford: In the “Sports” section, for example, photography becomes the moment itself. Photography becomes, “I was there.” Not just the artifact of the moment, but the moment.

Majeed: Then you further re-create that moment in this space of iconicity, this museum, and then it’s that moment that represents an entire movement, and era, and theme for this section, which is of politics and sports.

Bradford: One element that I think we move into here is this—is the stuff the general public likes about black people.

Majeed: The museum is very restrained in how much it wants to dislodge what you like. The leap to a triumphal narrative is really quick. You move from John Carlos to LeBron James and Michael Jordan very quickly without problematizing the premise; of course sports have a logical placement in the history that is mapped throughout the museum.

Bradford: These vitrines make the political aspect bloodless, because they give you a moment in time, iconized.

Majeed: Once you make a monument out of something, you know you can’t take it down.

Black American or American?

Majeed: This museum is a metaphorical rise through time, and it is not subtle about the movement upward being correlated with progress. So, of course, the uppermost galleries are devoted to art and music, because culture is that most rarefied of achievements. Yet these painting galleries are strangely disconnected from everything that has come before.

Bradford: This is one of those instances where the objects have no political or historical context. And if the viewer has not been in the history galleries, this is a seriously confusing space and a missed opportunity. At the same time, it shows us the canon of black art from Aaron Douglass to William T. Williams to Amy Sherald in a white-cube setting. I’m looking at two things right now. I’m looking at the William T. Williams, you see the work when you enter the space. But then also considering the Charles Alston quote facing it: “I don’t believe there is such a thing as ‘black art,’ though there’s certainly been a black experience. I’ve lived it. But it’s also an American experience.”

This is certainly something I’m familiar with, in terms of canonical black art, and the idea of representation at the center of it. So, William T. Williams starting his career in the 1960s. At that moment, there was this real push to make art for the people. There were stipulations about art speaking this explicit language of liberation. Maulana Karenga stated, “Our creative motif must be revolution; all art that does not discuss or contribute to revolutionary change is invalid.”15 That was an emphatic sentiment in the moment, yet NMAAHC introduced the art section with an abstract work from this period.

Majeed: Beginning with Williams’s abstract canvas immediately locates us in today’s blue chip understanding of “high art” and modernism. Black abstraction was famously left out of the Guggenheim’s Abstraction in the Twentieth Century: Total Risk, Freedom, Discipline (1996), which was “corrected” by Kellie Jones’s Energy/Experimentation: Black Artists and Abstraction, 1964–1980 at the Studio Museum in Harlem (2006). This opening appears to be part of that ongoing curatorial retort to places like the Whitney and the Guggenheim.

However, the juxtaposition with that Alston quote begs the question, What is black art? Or rather, What is black about this art? It’s been a contested issue for a long time, since the very instance of its emergence. Reminds me of how the late Zaha Hadid used to ridicule this dubious question: “Is there a female aesthetic in architecture?” What would be a feminist aesthetic in architecture? Is it merely because it’s made by a woman? Whereas here, it’s a little bit more complex. In how you’re going to deal with the idea of the black experience in a shared medium. It evinces the contradiction that Darby English and Charlotte Barat have addressed with regard to MoMA’s recent reshuffling of its priorities, “The sheer variousness of art embarrasses and sometimes explodes the unities upon which every premise of the art museum depends. In this sense the museum is in conflict with art.”16

Another decision which is entirely bizarre is the problematic relationship mapped in this museum between Africa and African American spirituality and/or creativity. A lot of African art that was appropriated by people like Alain Locke in order to furnish evidence of the creative origins of black people in America is not yet familiar to the general public, yet its appropriations and misappropriations, by all ethnicities, is everywhere. The National Museum of African Art is down the street, and by comparison to this museum, there’s hardly ever anyone in there.

Bradford: That question, that idea of the manufactured authenticity of these things came from somewhere in an expression of origins. Yet, I think there’s more of an understanding now and an actual connection in terms of diaspora. But, I think there’s also—it’s sort of a cheap tactic on some artists’ part.

Majeed: Perhaps also to confirm the audience’s expectations of authenticity, in terms of “African origins.” What it does is reinforce the idea of “primitive” Africa. Baldwin articulated this conundrum when living in Paris during the colonial period: “The French African comes from a region and a way of life which—at least from the American point of view—is exceedingly primitive, and where exploitation takes more naked forms.”17 This is all to say that primitivism is not delimited by race. At the center of the cultural galleries is an important work of Yoruba sculpture by a celebrated court artist, Olówè of Isè, from the early twentieth century, with the tripartite capital that inspired the design for this museum. What is it doing there? To me it shows that this is primarily a history museum; art is essential to the story, but more as witness to the narrative of progress than as a protagonist.

Bradford: The spaces downstairs definitively set up the major facets of the black narrative. What you’re saying about this embroidering is well stated. But remembering the origins and founding of this museum, the narrative and scale of it were just so eagerly anticipated and desperately desired. It is a pilgrimage site, not unlike Montgomery, but on a much grander scale. Black people in America have been seeking this affirmation, a public affirmation, a visible affirmation. An official endorsement by the country that the reality and repercussions of oppression are real.

Majeed: There’s something about the situatedness, the claim made by its location, alongside the kind of relics that they have downstairs that are important for people to see. That’s what relics have always been for: they carry the potency of the past and its potential into the present.

Bradford: People go there to affirm their sense of an existing narrative. In other galleries there are less well-known or specialized aspects of the black experience.

Majeed: The other thing I find interesting is that this museum is insistently about American history throughout. It locates you in the familiar before it tells you something that you didn’t know. How many people who are not black in this museum recognize the history they learned here? Or are they looking anthropologically, at somebody else’s country? Is it capable of bringing this plurality together as something universally recognizable? Or it is still “other,” even though it’s on the National Mall and is the National Museum?

Bradford: I wonder about the sense of the Smithsonian overall having these permeable boundaries. Because you’ve got African American history here, but does its existence mitigate inclusion in those other spaces that are dealing with the same history? Does the Smithsonian recognize responsibility to fully incorporate all of these different kinds of contributions into overall or essential American history?

Majeed: You have the competing, or perhaps complementary, museums. But once history is parceled out by ethnicity or race, it’s never going to satisfy everybody. We can’t have a comprehensive holistic view of history that represents everybody in one space, because it’s very difficult to have a synchronic presentation of the past if you don’t have an organizational device.

Bradford: Our sense of history is fluid, but I don’t think the museum allows that flexibility—the reality that this version of history will grow and change, and the viewer can ask questions and participate in the making of history.

Majeed: So we end where we began: Who is the audience for the EJI and NMAAHC? And what does the National Museum do to reach a different type of audience? Is it its job to reach a different kind of audience? Does it want to engage the people who do not know this history? I hope so, because we seem to be at the precipice of repeating it, if we don’t accept it as American history.18

Risham Majeed has a PhD in art history from Columbia University and is currently an assistant professor in the Department of Art History at Ithaca College. Majeed specializes in medieval art in western Europe and the historical arts of Africa. She has curated two exhibitions, Made to Move: African Nomadic Design and Get Real: Seeking Authenticity in African Art, with her students at Ithaca College. Her most recent publication is “Against Primitivism: Meyer Schapiro’s Early Writings on African and Medieval Art,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 71/72 (2019): 295–311. She is currently completing a book, “Primitive before Primitivism: Medieval and African Art in the 19th Century.”

Blake Bradford is a Philadelphia-based writer and educator. He shares his expertise on visual art and museums via conferences and panels, media appearances, and both mass-market and scholarly writing. Highlights of his work include his 2001 catalog entry for the seminal Freestyle exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem, “This Is Why: Expanding Opportunities for Educational Engagement,” presented at the 2016 National Council of Arts Administrators Conference, and the chapter “Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now” in the 2019 Routledge Companion to African American Art History. He holds a BA in art history from Williams College and an MA in art history from the University of Texas.

- James Baldwin, “Nobody Knows My Name: A Letter from the South,” in James Baldwin: Collected Essays, ed. Toni Morrison (New York: Literary Classics of America, 1998), 197. ↩

- Zadie Smith, “What Do We Want History to Do to Us?,” New York Review of Books, February 27, 2020. Smith’s essay was originally commissioned for Fons Americanus at the Tate Modern in London; see Clara Kim, ed., Hyundai Commission, Kara Walker: “Fons Americanus” (London: Tate Publishing, 2019), 32–53. ↩

- The unseen though palpable friction in Montgomery between official and forgotten is encapsulated in Smith’s observation, “Public art claiming to represent our collective memory is just as often a work of historical erasure and political manipulation. It is just as often the violent inscription of myth over truth, a form of ‘over-writing’—one story overlaid and thus obscuring another—modelled in three dimensions” (Smith, “What Do We Want History to Do to Us?,” 37). The Confederate monuments on the Capitol hill should be understood as myths “modelled in three dimensions.” ↩

- The project description adds, “Sir David Adjaye’s approach has been to establish both a meaningful relationship to this unique site as well as a strong conceptual resonance with America’s deep and longstanding African heritage.” For more on the Yoruba caryatid posts see John Pemberton III, “Art and Rituals for Yoruba Sacred Kings,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 15 (1989): 96–111, 174; Roslyn A. Walker, Olówè of Isè: A Yoruba Sculptor to Kings (Washington, DC: National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1998); and Nii O. Quarcoopome, “Three Works by Olówè of Isè,” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 85 (2011): 42–51. ↩

- Toni Morrison, quoted in Hilton Als, “Toni Morrison’s Profound and Unrelenting Vision,“ New Yorker January 27, 2020. ↩

- Throughout this piece we are employing the term “race” as it is grounded in the scientistic attitudes of the Enlightenment. Recent scholarship, emerging from medieval studies and literary history, has put forth claims that place the notion of “racism” as a premodern concept. See especially Cord J. Whitaker, Black Metaphors: How Modern Racism Emerged from Medieval Race-Thinking (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019); and Geraldine Heng, The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018). ↩

- The exhibition and catalog Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time: Art, Culture, and Exchange Across Medieval Saharan Africa (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019), curated and edited by Kathleen Bickford Berzock and held at the Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University, is a pathbreaking look at the networks of exchange between Africa and the globe in the medieval period. See also Sarah Guérin, “Ivory and the Ties That Bind,” in Whose Middle Ages?, ed. Andrew Albin et al. (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019), 140–53; François-Xavier Fauvelle, The Golden Rhinoceros: Histories of the African Middle Ages (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018); Michael Gomez, African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019); and Alisa Lagamma, ed., Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2020). ↩

- Research in Portugese archives related to the Kingdom of Kongo has enriched our understanding of this period. See especially Cécile Fromont, The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015); and Alisa Lagamma, ed., Kongo: Power and Majesty (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015). ↩

- The iconic image of a British slave ship packed with human cargo is the fulcrum for the “Middle Passage” displays; images in these galleries especially are used chiefly as evidence for the circumstances of the slave trade. The same image has come to be reappropriated as a symbol of struggle and liberation, a point fleshed out in Cheryl Finley, Committed to Memory: The Art of the Slave Ship Icon (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018). ↩

- The panel, “Who’s Not in the Picture?,” was organized by the head of education at the Frick Collection, Rika Burnham. The entire conversation is available on YouTube. ↩

- Aloïs Riegl, “The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin (1903),” translated by Kurt W. Foster and Diane Ghirardo, Oppositions 25 (1982): 21–51. ↩

- See Linda M. Heywood, Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017). ↩

- The exhibition pamphlet notes, “A shackled cast-iron stake is driven into the top of the column and pulls the flutes down into the center, destabilizing the pristine purity of the column’s classical form.” The title of the installation, Liberty, invokes the ideals of American democracy in its early years, which embraced Neoclassical style as an expression of continuity with Periclean Athens. Indeed, the architecture of the pavilion itself is Palladian, just as Jefferson’s home, Monticello, was modeled on Palladian classicism. Monticello now operates as a house museum and has finally highlighted Hemings’s quarters as an integral part of its history. ↩

- Monuments to women who were lynched are not nearly as prominent; but black women were also lynched for petty crimes and frequently raped beforehand. Many black women were also lynched for protesting the lynching of a male spouse or family member. There are more efforts underway to tell the stories of the women subjected to racial violence: see especially the Mary Turner project; Julie Buckner Armstrong, Mary Turner and the Memory of Lynching (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011); Leon Litwack, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (New York: Knopf, 1999); and Evelyn Simien, Gender and Lynching: The Politics of Memory (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). Black women were more involved in antilynching movements and functioned as catalysts for drawing attention to racial violence at a time when the print media ignored the issue. See Mary B. Murphy, “The Eyes of the World Are upon Us: The Politics of Lynching,” in Jim Crow Capital: Women and Black Freedom Struggles in Washington, D.C., 1920–1945 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 46–71; and Jordynn Jack and Lucy Massagee, “Ladies and Lynching: Southern Women, Civil Rights, and the Rhetoric of Interracial Cooperation,” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 14 (2011): 493–510. ↩

- Maulana Karenga, “On Black Art,” Black Theatre 4 (1969). ↩

- Charlotte Barat and Darby English, “Blackness at MoMA: A Legacy of Deficit,” in Among Others: Blackness at MoMA, ed. English and Barat (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2019), 15. ↩

- James Baldwin, “Encounter on the Seine: Black Meets Brown,” in Baldwin, Collected Essays, 88. ↩

- Just as this article was going to press we learned of the murder of Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia, which the mayor of Atlanta, Keisha Lance Bottoms, characterized as a “lynching.” See George Yancy, “Ahmaud Arbery and the Ghosts of Lynchings Past,” New York Times, May 12, 2020. ↩