Editor’s Note:

Contemporary Projects features original projects driven by artists, designers, or curators, highlighting diverse, critical forms of knowledge directly produced by art and design practices.

As part of our editorial work to place contemporary art practice in conversation with our archives, we’ve paired Pato Hebert’s “Malapropisms: Track Changes,” in which the artist-organizer draws connections between his work on HIV-prevention and advocacy to addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, with an interview from the AJO archives in which Rudy Lemcke discussed the poetics and politics of AIDS in light of his work in the 2014–16 traveling exhibition Art AIDS America (“Immemorial: The Poetics of AIDS,” from June 2015).

Journal fragment, December 8, 2023

Took four gaba anoche after barely sleeping Wed night. I woke to pee and felt like I could’ve gone back down for another three hours. Tried but couldn’t fall back to sleep. Got up only to be able to do little more than scroll and scroll. The brain fog is bad today. Brain fog forever. My BFF.

Long Haulers

Long COVID (LC) is a chronic illness that has impacted nearly 7 percent of all adults living in the United States. At least 65 million people are estimated to be living with long COVID worldwide. Long COVID is the persistence of symptoms long after acute infection. There are dozens of physical manifestations, with fatigue and respiratory, neurological, cognitive, cardiac, and gastrointestinal symptoms among the most common. I have experienced all of these and more. Many of us who are living with long COVID in English-speaking countries call ourselves “long haulers.” We endure. Long haulers are also mobilizing on countless fronts, including through activism and organizing, journalism, and community-led research, consistently taking our collective wellness into our own hands. The long COVID movement is especially noteworthy because many of us are constantly contending with fatigue and wrestling with what it means to mobilize in a pandemic that is caused by an airborne virus. Movement building is difficult when rest is not always available to the chronically ill body, and when rest does not necessarily guarantee replenishment or relief. We are so often very tired. At times I wonder if my life force is steadily ebbing. Then I remind myself that it might just as easily be my ableism abating. Our worth is not based on what or how much we do. Perhaps I am slowly learning to better pace.

Malapropisms

A malapropism is the unintended use of one word in place of another. My COVID-related malapropisms happen all the time—in real time while working with people, in drafts of emails, and as seeds in my journal only to be discovered during future reviews. I first became infected near the beginning of the pandemic. At some point in early 2020, I inhaled the virus as it migrated like an ember, settling in and setting my throat and nervous system aflame. I have since had to share this body with the unwelcome guest known as the coronavirus. This has caused me to reckon with my own ableism in stark and demanding ways as I have transitioned to someone now adjusting to life with a disability.

One of my most persistent symptoms is aphasia, a neurological condition that creates challenges with recalling and processing language. The Malapropisms series is my attempt to make a visual artwork out of and in collaboration with this condition. I wrote briefly about this in 2021 for my contribution to the groundbreaking collection edited by Fiona Lowenstein, The Long COVID Survival Guide. In my essay, “COVID Can’t Be Outpaced,” I say:

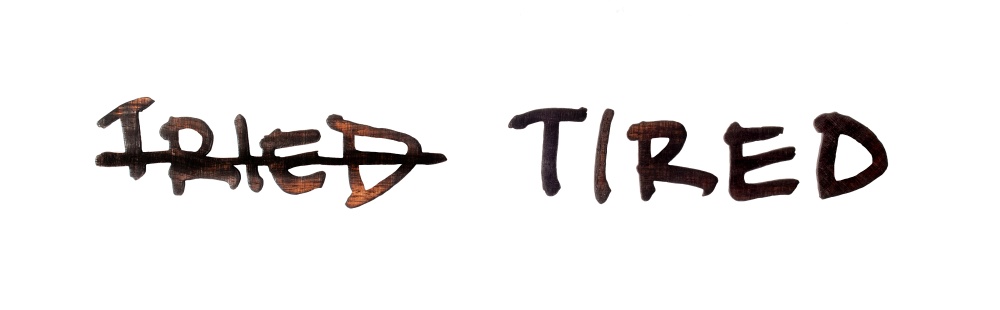

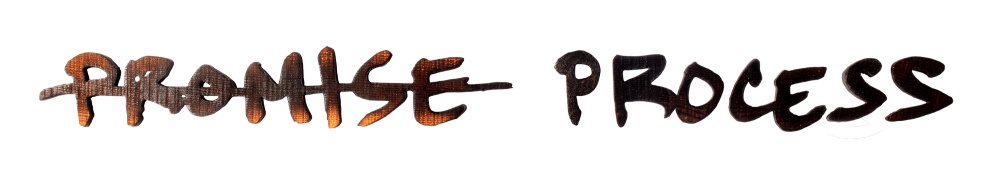

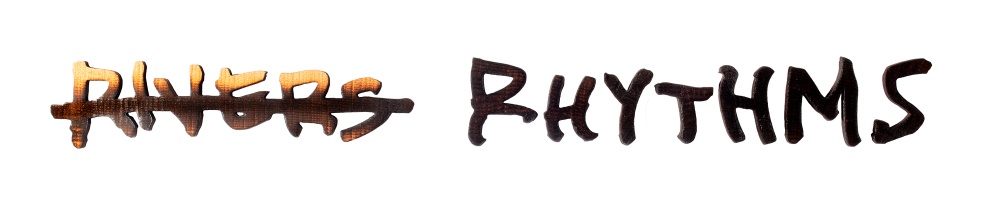

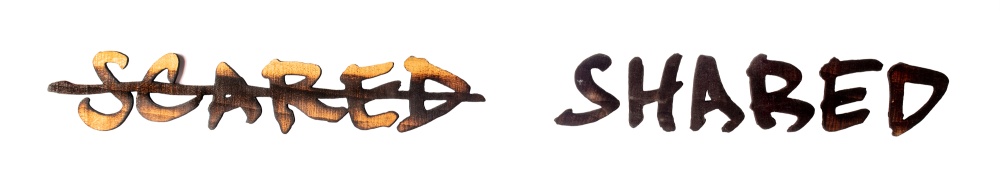

“This unwanted cognitive confusion happens all the time. Words slip in and out of one another, alternately entangled and playing peek-a-boo. It makes writing or public speaking or trying to share intimate thoughts with loved ones rather interesting. While talking, I mix up words that start with the same later letter or are distant relatives that share a syllable with similar vowels. Often the mix-ups are incorrect homonyms. Sometimes, it’s just a misplaced letter or two that changes the entire word, derailed from my intended meaning . . . I keep notes of these jumbles on my phone, a poem in pairs that incrementally evolves in juxtaposed parts . . . dimension dementia; whole hole; mix mask; overdoes overdoses; art heart.”

For the publication of that essay, the designer, editors, and I decided to include examples of both words, with the malapropism appearing struck through followed by the intended word. This helped to visualize and embody the neurological condition I am living.

Long COVID is quite the prolific coauthor. After all these years, we’re still figuring out how best to work together, and occasionally even get along. LC sends me these couplets and then pesters me to do something with them. The malapropisms just keep accumulating. I dutifully gather and archive them. My list is now eight pages long. Keeping this list offers me a sense of open-ended play. Transcribing the malapropisms into my handwriting and then to wood, touched by precise lasers and open flame, invites a transformation. Long COVID, language, my synapses, the trees, and I are all playing a game together. Presenting them as art lets you in on the game too. This potential for transformation is but one of many reasons why I make art. Art allows us to abstract, narrate, apprehend, bend, contend with, bow to, and reimagine our lives, our relations. And this makes me feel infinitely more present, connected, and free.

The Drawn Word

My hand is increasingly unsteady as I age, a tremor wobbling into view a bit more each year. COVID seems to have intensified this by disrupting my fine motor skills. Precision handwork is harder for me now while carving wood or doing a watercolor wash or digitally outlining a selection in Photoshop. Still, my love of handwriting persists even as it continues to disappear from our daily lives. I think of handwriting as the drawn word. I savor it on nearly every encounter—people’s Post-it notes or increasingly infrequent cards, our quick scribbles and scrawls. I love how handwriting can presence a person—their personality and pace, education or social class. There is something quite intimate about handwriting, which is only more beautiful to me the more anachronistic it becomes. Calligraphy is a rich and storied art form centuries old in some traditions. I marvel at its elegance and discipline. But I am just as mesmerized by chicken scratch and scraps of lists. I love seeing language given form. This is why I geek out on typography too. Yet the uniqueness of each human’s handwriting calls when I am looking for an extra level of immediacy in an artwork.

If you trace the communities and people disproportionately impacted by a disease like HIV or long COVID, you find a contour drawing of that society’s inequalities, which is to say its cruelty, values, and neglect. It ain’t a pretty picture. But those of us inhabiting these realities make magic and beauty every day. We learn to live in a different set of relations, including with the more than human. Long COVID is, in part, a complex interspecies dance that disassembles any sense of human arrogance or autonomy. And during lockdown, it left me craving touch. It also made me more deeply appreciative than ever of the land, skies, water, and relations that make interconnected thriving possible. I was so grateful to eventually be out of bed, outside, still able to breathe and move. During my slow, gentle walks in Los Angeles’s Elysian Park, I found myself particularly drawn to wood and stone with their different densities, scales, and durations of life. I think developing long COVID made me yearn to not simply contract from the world, but rather to extend and deepen my connection with other living relations. This pushed me out of my own self-absorption and challenged me to consider existence in multiple forms and varying registers of time. It also opened me to new rhythms and forms of art making, ones that might meander and accrete over the long haul.

Char

Because I have long been interested in combining analog and digital processes in artmaking, it made sense to experiment with my scanned handwriting and laser cut wood in the making of these early Malapropisms prototypes. I prioritized rosewood from Panamá, live oak from California, and red cedar from Washington, salvaged when possible and repurposed. Even as one-eighth-inch boards, the trees are still present and generously giving of their lives. The malapropisms are crossed out via strikethroughs singed upon the wood’s heated fibers. These are then juxtaposed with the intended words appearing in stark charred beauty. The charring of the wood might allude to COVID’s inflammation of our immune system or one of my strangest symptoms—phantom smells of burning wood and wires. But the charring might also speak to the transformation that can occur with heat, the protective aspects that flame can have on wood, and the resilience and regenerative potential of ecosystems cyclically exposed to wildfire—or reciprocal stewarding.

In my LA neighborhood, gangs vie for primacy via the walls at the various entrances to our blocks. They spray dismissals of their rivals by crossing out one another’s tags. Theirs is an endlessly tense stream of throwing up placas and canceling them out before (and then after) landlords and city crews come through to reset the walls to not-quite-right shades of forgetting. The blank walls then become an invitation for the process to start all over again as people say we are here, this is ours.

But my malapropisms are decidedly different from a text redacted. Both Jean-Michel Basquiat and medieval scribes alike knew that crossing out can call attention more than cancel out. A strikethrough can be a highlighter too. The malapropisms aren’t just edits and they are not erasures. They are slippages caused by long COVID-inflected synapses working differently. Sometimes I catch these glitches and make note of their gorgeous potential. Rather than see them simply as errors, I instead like to think of them as somewhat eccentric cousins merge-called by the coronavirus to keep the conversation curious. The malapropism is what makes the intended word more interesting. It’s in the juxtaposition and simultaneity that the poetics emerge. Long COVID is here, whether we choose to see it or not. There is no redacting it, no making it disappear, no crossing it off the to-do list. Our long hauling bodies won’t allow it.

Insistence

It is painful, if unsurprising, to see governments, businesses, and institutions having declared the COVID-19 pandemic over, incentivizing us to move on. Excruciating to experience our beloveds assuming the same. So little consideration of masking or filtration at the holiday gathering. Why spoil the party when the ableist show must go on? We are in a kind of collective disassociation cum forgetting, perhaps induced by an exhaustion from the trauma of this ongoing pandemic. But for those of us who are sick and disabled, the bodies in which we live, the bodies we live with, will not let us forget. And we are not trying to. We are trying to survive—by deploying all that our bodies and our crip kin have taught us. A collective insistence on persistence. As I approach my four-year illiversary of being sick, I would be lost and bereft without my long COVID family.

Strikethrough

Exhaustion is ever-present for many of us. Certainly for me. And my thighs are often seized with tension, my COVID-inflamed nervous system fried. But lately I have had a new symptom. It is infrequent yet still frightening. I have moments of temporarily being unable to swallow. The ensuing anxiety rises immediately, fast and strong. I have to bite down and push my tongue to the roof of my mouth to activate my salivary glands. Scramble to find something to drink to force the throat to engage. Too much sugar? Too little sleep? Excessive stress? I can make no demands. The body refuses to work. It is going on strike. Too much extracted labor. It resists its way toward rest. A new way of being. A chronic reconditioning that I have no choice but to adjust to and accept. To inspect and respect. To involve and evolve.

I have no two-word poems against long COVID’s agile and persistent impingement. Okay COVID. Fuck off. I guess. Maybe so. Alright then. There are currently no cures. For preventing infection, we know the layered help of masks, vaccines, ventilation, filtration. But we also need effective policy, political will, paid sick leave, free and accessible healthcare, safe housing, more research, an end to red tape. Lots of folks can’t even get medicine when they become infected or reinfected. When I was reinfected and tried to order Paxlovid, it came out Paxlivid. I rambunctiously roar with laughter every time I tell this story. Tending to and surviving long COVID cannot happen without our writers and artists, humor and hopefulness. Nor can we thrive without disability justice, mutual aid, and one another. Breath and viruses aren’t the only things shared between us. Tactics, imagination, and care are too.

Journal notes, December 11, 2023

World AIDS Day was just ten days ago. This year I am remembering James, Kenny and Shiv in particular, and always querido Horacio. The 34th anniversary of the US invasion of Panamá is nine days from now. I remember well los cuentos de mi abuelita’s terror, her shrieks at the US military planes screaming overhead. This year, in between these two days of December mourning, hundreds and hundreds of Palestinian people have been killed by munitions made in the United States and paid for by US tax dollars, mine included. We must somehow make space for our horror and grief, justice and hope, rage and reimagining, change and new ways.

I keep thinking about that destructive and unjust invasion of Panamá that began on December 20, 1989. And how the very first Day Without Art occurred just a few weeks prior to that. I found this on Visual AIDS’ site:

“In 1989, in response to the worsening AIDS crisis and coinciding with the World Health Organization’s second annual World AIDS Day on December 1, Visual AIDS organized the first Day Without Art.A committee of art workers (curators, writers, and art professionals) sent out a call for “mourning and action in response to the AIDS crisis” that would celebrate the lives and achievements of lost colleagues and friends; encourage caring for all people with AIDS; educating diverse publics about HIV infection; and finding a cure. More than 800 arts organizations, museums and galleries throughout the US participated by shrouding artworks and replacing them with information about HIV and safer sex, locking their doors or dimming their lights, and producing exhibitions, programs, readings, memorials, rituals, and performances. Visual AIDS coordinated this network mega-event by producing a poster and handling promotion and press relations.”

In the mid-1990s, during December’s annual arrival, my queer friends and I used to acerbically joke about wanting a Day Without AIDS. HIV was wreaking havoc on so many of our lives. It still is. Stigma, discrimination, inequity, isolation and frustration are all busy finding new ways to stay alive come 2024. But we and our gallows humor and irreverent joy also persist. Our sense of priorities does too. Activist groups with banners, chants and actions remind us to fund healthcare not warfare. It’s once again HIV/AIDS season, meaning the time of year when World AIDS Day asks the broader public to remember all whom we have lost, all who still live with HIV long-term in these pandemics ongoing, all who find numerous ways to thrive. For some of us, it means more emotions and calendar commitments than we can seemingly manage. I had the privilege of helping to jury this year’s program, Everyone I Know Is Sick, with those amazing films by Dolissa, Lili and others. And on Wednesday, aAliy and I will be talking about “The Role of Artists in Justice Movements.” I need these kinds of conversations and connections, these chronic illness lifelines. I would love for our world to know at least a Day Without HIV or Long COVID, lupus, MS or ME/CFS. But when Gazan hospitals and lives are relentlessly bombarded into inoperative carnage, I would simply welcome an immediate ceasefire now.

Pato Hebert is an artist, teacher and organizer. His work probes the challenges and possibilities of interconnectedness. His creative projects have been presented at the Centro de Arte Contemporáneo in Quito, Beton7 in Athens, the Ballarat International Foto Biennale, the Songzhuang International Photo Biennale, and IHLIA LGBT Heritage in Amsterdam. He is also a COVID-19 long hauler, living with the ongoing impacts of the coronavirus since March of 2020 and publicly addressing the pandemic through creativity and community building. His solo exhibition about long COVID, Lingering, was curated by Ruti Talmor and debuted at Pitzer College in 2022. Hebert serves as Chair and teaches in the Department of Art & Public Policy at Tisch School of the Arts, New York University, where his students have thrice nominated him for the David Payne-Carter Award for Teaching Excellence.