This review originally appeared in Art Journal, 84, no. 2 (Summer 2025)

Edges of Ailey, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 25, 2024–February 9, 2025

Edges of Ailey, ed. Adrienne Edwards, Exh. cat., Whitney Museum of American Art, 2024. 388 pp.; 259 color ills., 167 b/w; $65

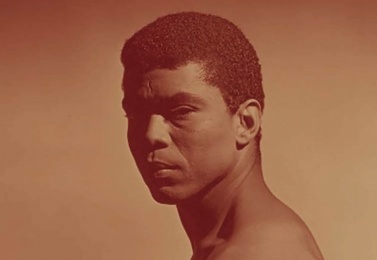

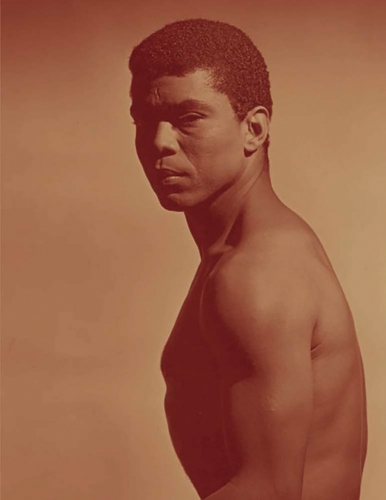

Choreographer and artist Alvin Ailey (1931–1989) functions as a conduit for glimpsing histories of Blackness in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s exhibition and eponymous catalog, Edges of Ailey. A combinatory selection of Ailey’s archival ephemera and visual materials—Ailey’s journals, dance company promotional materials, photographs, videos, and artworks—Edges of Ailey marks the first comprehensive exhibition to frame histories of Black visualization and material culture through the life and legacy of this mainstream choreographer. Whitney curator Adrienne Edwards takes a multilayered approach that attends to Ailey’s life as “kaleidoscopic” and “polyvocal,” that is, both representative of the individual and indicative of a wider, constellatory body of Blackness. As she explains in her introductory catalog essay, “Such Sweet Thunder,” “What Mr. Ailey’s work suggests is that a void of love towards Blackness does not confine or undermine what Blackness is and how it might be presented; and that although racist sentiments are prevalent in the world … they do not overwhelm how we make our worlds and revel in them” (19). Edwards asks her audience to approach Ailey, his archives, and his works as vectors within this constellation of Blackness, and to recognize his artistic singularity as a constant unraveling of Black(ened) histories and futures.1

As it unfolds throughout the third and fifth-floor galleries of the museum, Edges of Ailey reproduces these constellations of being with visual and sonic resonance. A suite of performances occupies the museum’s third-floor theater, featuring a rotation of works from the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT), its offshoots Ailey II and the Ailey School, as well as commissioned dances from Ronald K. Brown; Trajal Harrell; Bill T. Jones; Ralph Lemon and Kevin Beasley; Sarah Michelson; Okwui Okpokwasili and Peter Born; Will Rawls; Matthew Rushing; Yusha-Marie Sorzano; and Jawole Willa Jo Zollar. In the fifth-floor galleries, songs such as the nineteenth-century African American spiritual, “I’ve Been ‘Buked and I’ve Been Scorned” and Leon Russell’s “A Song for You” punctuate audio from interviews, broadcasts, and spoken love letters—comprising an Ailey-inspired ‘mixtape’ that spills out into the museum’s hallways. The soundscape correlates with a projection of archival footage that runs along the upper perimeter of the gallery walls. Scenes from Ailey’s life create a warm glow throughout the room, as the eighteen-channel video installation traverses several decades of recordings from Ailey’s eponymous dance company. Below this perimeter, the room optically vibrates with a sensuous crimson hue, a nod to the velvet spaces of the proscenium theater, but even deeper, a call to Ailey’s notion of “blood memories”—as suggested by a wall label referring to “[Ailey’s] recollections of the blues, spirituals, gospel, work songs, all those things going on in Texas in the 1930s during the Depression.” Ailey’s blood memories thus become the substructures of Edwards’s exhibition.

Scattered about the space, angular platforms are drenched in that familiar blood-red hue. They seem to rise out of the floor to produce half-walls, pedestals, and semi-pyramidal forms that subtend the medley of objects. The irregular display creates an archipelagic effect that fragments the space and collection into several thematic groupings, which Edwards identifies as—but does not limit to—Southern Imaginary, Black Spirituality, Black Migration, Black Liberation, Black Women, Ailey’s Collaborators, Black Music, Ailey’s Influences, and After Ailey (331). Looking at Benny Andrews’s painting, The Way to the Promised Land (Revival Scene), of 1994, one’s eye catches objects within the periphery, generating a connection between surrounding works such as Theaster Gates’s Minority Majority (2012), Sam Doyle’s Frank Capers (1970), and Charles White’s Preacher (1952). The visual coalescing intimately associates Black spirituality and transcendence with the surreptitious histories of Black survival, encompassing resistance, pleasure, and queerness. Edwards’s fractal approach has multiple points of origin: she first recognizes the acute reference to Ailey’s Archipelago, of 1970, which blended the disciplinary languages of classical ballet and modern dance to explore a cultural relationality of locomotion. However, the specificity of this reference recalls a wider theoretical positioning of the archipelago as a mode of ambiguous being correspondent with ontological Blackness.

In a parallel vein, the exhibition catalog approaches Ailey through the diffracted voices of those closest to him—even if their proximity is one of posthumous familiarity. An anthology of essays, interviews, and letters, the catalog comprises a polyvocal expression of love and nostalgic reminiscing that literalizes an era “after Ailey.” Dancer and scholar Thomas DeFrantz, whose extensive publications include a book on Ailey’s Revelations, presents an emphatic letter to the choreographer. DeFrantz’s piece is an accumulation of reverence, simultaneously effusing over, relating to, inquiring of, and thanking Ailey for his work as a gay Black man in the public eye. Similar sentiments ring throughout the catalog, as former Ailey dancers Masazumi Chaya, Judith Jamison, Sylvia Waters and Aimee Meredith Cox; luminaries Adrienne Edwards, Malik Gaines, Horace D. Ballard, Uri McMillan, Ariel Osterweis, and numerous others come together in homage to Ailey. However, their voices culminate in a passage offered by DeFrantz, whose letter articulates this larger, collective indebtedness:

None of us working in dance or Black visual cultures or maybe even music moves without relationship to what you created, as strange as that surely sounds. We all belong to you somehow; we are among your edges and your legacies as people who wonder about dance. We think of you and the most famous images of your form from the 1960s onward: beautiful of body and unflappable integrity of commitment to give dance back to the people. We people (101).One must negotiate with the exhibition and the catalog’s aberrant construction, both installation and publication forging individualistic paths of knowing Ailey. Archipelagic thinking, an ontological framework commonly attributed to Martinican poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant, emphasizes the refractory nature of Blackness as the means for perspicacious being. Black diversities, whether rendered through displacement or migration, are historically incompatible with the colonialist machinations of a continental identity. According to Glissant, archipelagic thinking “accepts the practice of the detour, which is not the same as fleeing or giving up. It recognizes the range of the imaginations of the [diasporic] Trace … it means being in harmony with the world as it is diffracted in archipelagos, precisely, these sorts of diversities in spatial expanses which nevertheless rally coastlines and marry horizons.”2 Intentional or not, Edwards’s invocation of the archipelagic as geographic and geologic substructure parallels Ailey’s overarching concept of blood memory as an orientation of Blackness. Artwork and archive intermingle through the cross-relationality of blood memory, pulling from the choreographer’s diverse range of interests, curiosities, and obsessions to promote a glimpse of Ailey beyond the legacy already inherited.

So much of Edwards’s curatorial process is a disruptive act of glimpsing, as Edges of Ailey—through its very invocation of disparate visual, textual and corporeal materials—reconsolidates a history of Ailey’s dual being, one split between the public and the private. Edwards recognizes the intentional bifurcation of Ailey’s archive as an integral, yet contradictory, component in his [re]narrativization. Notebooks, videos, photographs, letters and related communication, recordings, posters, books, and typescripts constitute two halves of Ailey’s material shadow. On the one hand, ephemera related to the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT) has become part of a larger archival system. Once transferred to the Library of Congress in 2006, this half of Ailey would come to represent a public-facing legacy open to conscription for the sociologic amelioration of Black life. On the other hand, one finds Ailey’s personal effects through an internal monologue of written and visual materials that reveal moments of Black queer existence. This latter collection is part of the Allan Gray Family Personal Papers of Alvin Ailey, held at the Black Archives of Mid-America in Kansas City. As Edwards explains, her reunification of these two halves is intended as a political act that underscores Ailey’s actuality as contradictorily whole, despite an archival bifurcation dictated by anti-Blackness (12). Edges of Ailey thus rekindles a history of queer being through the serendipitous assemblages of Black art, dance, and text, revealing what Edwards refers to as “a politics of sparkle,” one designating how pleasure and embrace of Blackness persists in the very essence of Black being (118).

In his catalog essay, “Elegant Mutinies,” curator Horace Ballard engages with Ailey’s archival and embodied partitioning as evoking a “Black Church tradition,” the term designating a metaphor of Blackness and redress rooted in histories of Christian doxa and concomitant white domination (59). As a colonial project, religion was gifted, sometimes forcefully, to subjugated communities in an attempt to justify the violence and domination of colonialism, chattel slavery, and segregation (60). With time, even these recognized sentiments of being became cause for white concern; the Black church was a metaphorical transfiguration of Blackness, built from biblical narratives of violence, martyrdom, and survival that culminate in the possibility of retribution and liberation. Simultaneously, Ballard proposes the Black church tradition as metonymic of Blackness, encompassing spheres of Black communion and kinship; expressions of Black soul performance; a “larger, gothic architectonic relationality” known as the South; and the customs of Black respectability politics (60–61). Seemingly disparate in form, the Black church represents a mode of being that historically separated the public from the private as a means for redress and retribution couched in clandestine desires.

Nevertheless, the Black church tradition is founded on the separation of one’s life, a partitioning of expectation and desire that began with the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Ballard reveals a tension of being that continues to conscript the Black body in a larger operation of freedom, while simultaneously denying the pleasures that define true liberation. In many ways, Ballard suggests that Ailey’s difficulty in choosing between closeted-ness and out-ness is prescriptive of the contradictory mélange of public and private manifested through histories of the Black church tradition. And yet, this paradox speaks to the nuanced realities of the Black church as an origin of soul—a “co-constitutive alliance between the sacred and the secular in individual and collective Black lives”—which emanates from the frictional realities synonymous with Blackness (61–63). Reminiscent of scholar Saidiya Hartman’s thought on Blackness and pleasure, soul becomes a mode of redress that is a “stealing away” of pleasure through performances of Blackness.3 As Hartman explains, “Stealing away involved unlicensed movement, collective assembly, and an abrogation of the terms of subjection in acts as simple as … making nocturnal visits to loved ones.”4 Whether described as being in and of the Black church, blood memories, or even “stealing away,” Ailey’s choreographies issued out of a contentious history of Blackness and being that deemed instances of pleasure and truth to always already be evocative of dissent.

Ailey’s choreographic and written legacies reveal an imbrication of the public and private to which Ballard and Hartman refer. Throughout the exhibition, visitors are able to read through various Ailey journal entries that divulge points of inspiration directly connected to his life as both queer and Black. One such entry outlined types of love and relationality that contributed to Ailey’s series, Love Songs (1972), which enumerates types of sexual and platonic love beginning with a duet representing the love of man for woman. As the entry continues, one finds multiple pairings: the love of man for man; of woman for woman; of men for women “group dance—orgy slow moving”; of parental love for children, both “protective” and “instructive”; of man for man “helpful–brotherly”; of a “very deep love of man for woman,” which is described as a solo; and finally of “love for self” (305). As Edwards points out in a dialogue with performance scholar Claire Bishop, these lists communicate an underlying essence of queer relationality that, while unspoken, permeates the very archive Ailey rendered as separate. Edwards’s decision to incorporate Ailey’s inner monologue via notebook and journal entry creates space for Black queer being as profuse and foundational to the structures of being in and of the world today. Edwards writes, “We need to speak of Mr. Ailey in the genealogy of Black gay people before and alongside him, from figures in the Harlem Renaissance … to the civil rights era …” (21). One cannot untether Ailey’s queerness from his Blackness, just as one cannot unravel the bind of Blackness and modern humanist projects.

Such is the tipping point of this exhibition. Edges of Ailey highlights the very imbrication of Blackness and modernity through its various references to dance and visual art. Throughout both exhibition and catalog, Edwards is forthright in her pairing of archive and artwork, understanding that although Ailey may not, and sometimes cannot, have encountered some of the included works, they characterize the ongoing evolutions of American modernist theory and praxis. One of the exhibition’s central plinth-archipelagos supports David Hammons’s Untitled (1992), a bed of gray stones that give birth to long, spiderlike tendrils of human hair. An accretion of the organic and inorganic worlds, the piece gathers found materials such as wire, metallic mylar, string, plastic beads, pantyhose, and a sledgehammer, each item covered with kinked tendrils of discarded hair from Harlem barbershops. Hammons transforms the ephemera of life into something unrecognizable, visually and physically obfuscating objects beneath traces of the Black body. Adjacent to Hammons’s work is Sam Gilliam’s Untitled (Black) of 1978, one of several monochromes that similarly obscure vibrancies of color through the compression and compounding of black acrylic. In both works, a tactile, material density pulls the viewer into a spatial and emotional dialogue. While the viewer’s proximity to the surfaces of sculpture and painting suggest surrender, both artworks remain indeterminate, obscuring the world beneath a Black(ened) exterior.

Responding to the concomitant pressures of abstraction and purity, Hammons and Gilliam work within a visceral and resistive practice of visualization that ruptures the paradigms of capital-M Modernism. As both sociopolitical existence and artistic practice, Modernism is historically built on the extraction of Black culture and labor, beginning with the Middle Passage and persisting through the anti-Black violence of our own era. And one would be remiss to ignore the epitome of white modernism, Kazimir Malevich’s painting, Black Square (1915), as visually built atop a racist joke of 1898.5 Modernism is historically built upon the very substance of Black(ened) flesh, a mutable material with endless potentiality. The same holds true for modern dance, which continuously looked to Black, Indigenous, and non-white cultural forms as fodder for experimentation. As scholar Malik Gaines explains in his catalog essay, “Modernity and its aesthetic, modernism, are thorny problems in the afterlife of the colony. That problematization is the intrinsic material of Ailey’s work” (42). An Ailey dance like Revelations (1960) opened the world to a vernacular of Black modernist dance that endured betwixt the concert stage and the reality of being, the representation and the real, the public and the private. To make work in this world—a world still reeling in the wake of slavery—is to participate in a dialogue of modernist conditions, recentering the experiences of Blackness as multiply beautiful and violent. While Ailey was never a political figure, his work bespeaks a Black expressivity that, though tinged by histories of domination, re-present the ever-changing constellations of Blackness.

L. Annalise Palmer is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Art History at Penn State University, University Park.

- I invoke Iman Jackson’s use of “black(ened)” in recognition of race that is not possessed, but is possessive; see Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World (NYU Press, 2020). ↩

- Édouard Glissant, Treatise on the Whole-World, trans. Celia Britton, Glissant Translation Project (Liverpool University Press, 2020), 18. ↩

- Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America, rev. and updated ed. (W. W. Norton & Company, 2022), 110–13. ↩

- Hartman, 113. ↩

- Steven Nelson and Huey Copeland, eds., Black Modernisms in the Transatlantic World, (Yale University Press, 2023), 5–8. ↩